Downtown is a large and important piece of Oakland’s economic puzzle. It’s the city’s financial center, home to corporations and a myriad of small businesses and community organizations. It’s where our public officials and administrators go to work every day and a destination for commuting office workers. And it’s a residential neighborhood with an increasing number of urban dwellings and high rises.

The Oaklandside is partnering with Oakland North and Oakland Lowdown to examine what’s working well and what isn’t for people in our urban center. Read more.

Illustration by Bea Hayward

As part of our ongoing series exploring how and for whom downtown Oakland works, we talked to economists, business owners and leaders of local business improvement districts, sifted through city economic reports and studies, and looked at available data on sales, business, property, and hotel taxes to better understand how downtown’s economy functions, and whether it’s running smoothly as a crucial economic engine for the city as a whole. We also examined how commerce downtown has changed in important ways over the decades, including in recent years as a result of the pandemic.

The downtown Oakland of old: the department store model

Downtown Oakland’s landscape was quite literally designed with department stores in mind. Take, for example, the clip below from Florence B. Crocker’s 1925 book, Who Made Oakland? In the book, Crocker published a variety of letters from “Oakland’s Guardian Angels”—anonymous writers whom Crocker claimed had mysteriously written to her with opinions about the city’s growth and development. Their letters highlight dozens of entrepreneurs whose businesses flourished as Oakland grew in the early 1900s. One of them was furniture maker HK Jackson, whose department store is pictured below. Jackson’s store was located where the federal buildings are currently, a change that represents downtown Oakland’s old status as first and foremost a commercial center.

“With our magnificent department stores, our wonderful factories, our beautiful theatres, and everything in the way of convenience that the largest cities in the United States can boast of,” reads the letter, “We most urgently urge you to keep your money in Oakland.”

Even in the mid-1970s, the department store model was driving development decisions downtown. A report published by the city’s Redevelopment Agency titled “Patterns of Growth: A Summary of Redevelopment in Oakland” in 1974 makes clear the city’s prioritization of major retail shopping downtown, and its language bears resemblance to the clip from the 1920s:

“In addition to bringing thousands of workers into City Center, the development’s urban shopping center component, which will include three major department stores and approximately 100 small specialty stores, will attract shoppers from throughout the Bay Area. They will be able to shop in the comfort of an enclosed multi-tiered mall with interior landscaping and convenient areas to pause and relax.”

The redevelopment report also discussed the building of new office buildings and commercial centers, such as the Clorox Building, and City Center Plaza. These buildings were meant to bring thousands of workers downtown; the plan called these plans “the beginnings of downtown Oakland’s ‘turnaround.’”

For many years, the major commercial and retail areas of downtown Oakland connected seamlessly with the adjacent Auto Row corridor on Broadway. For years, Auto Row was one of the city’s main revenue generators: When Ford’s dealership closed in 2008, it was reported by Angela Hill of The East Bay Express that the dealerships (about a dozen in total) had brought $3.2 million to Oakland by way of retail tax revenue each year—roughly $4.6 million adjusted for inflation.

By 2008, however, the decades-old paradigm that placed downtown as a home for commercial and retail businesses had begun to shift in favor of more residential units. As mayor, Jerry Brown began the “10k Plan,” hoping to attract 10,000 residents into downtown Oakland with new housing developments. Brown’s plan was criticized at the time by some for not including adequate below-market-rate housing. But it did result in thousands of new residential units and over two decades later, the city has largely kept housing centered in its long-term plans for downtown.

Office work downtown hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels

Even with the influx of residential property, downtown Oakalnd is also still very much a place of work. The greater downtown area provides the largest percentage of citywide jobs at 38% and employs nearly 100% of Oakland’s government staff, according to numbers compiled for the city by Economic & Planning Systems.

Downtown also holds 70% of the entire city’s office inventory, per the same report. This concentration of offices—similar to cities around the country—has fueled much debate and study about the future of cities and what role commercial real estate will and should play in a healthy urban economy.

One infamous study in 2022 described the pandemic’s impact on cities as an “office real estate apocalypse” and “urban doom loop”—a complete game-changer for big-city downtowns: “The key takeaway from our analysis is that WFH is shaping up to massively disrupt the value of commercial office real estate in the short and medium term,” wrote its authors.

That disruption is still upon us. The city’s Economic Dashboard shows downtown office vacancy rates remain elevated at about 16%, roughly on par with peak levels during the pandemic. At the beginning of 2010, by comparison, the vacancy rate stood at 10%, and it dropped to as low as 6% in early 2016.

“Part of this reflects the fact that downtown saw a significant amount of new office space delivered during the pandemic when offices sat largely vacant,” the report states.

Vacant offices mean fewer companies and people paying rent, which leads to less property tax revenue for the city. For offices that do become occupied, the latest data from the city’s dashboard shows a slight downward trend in the cost of renting commercial space, following steady increases from 2010 to 2020. The going rate for commercial space downtown currently hovers at around $51 per square foot.

In recent years, several big companies have reneged on downtown plans that had the potential to make a big impact on Oakland’s economy. In 2017, Uber ditched a plan to establish its headquarters in Uptown. In 2020, Kaiser Permanente—the city’s largest employer—walked away from a plan to build a 1.6 million-square-foot office tower at 2100 Telegraph Ave. In 2021, X (formerly Twitter) signed a lease on 66,000 square feet of downtown Oakland office space, which the company subleased before planning to occupy it. But in August 2022, the tech giant announced it was abandoning that plan.

But others have chosen to invest in downtown, boosting office occupancy and ownership rates there. In 2019, Block Inc. (formerly Square) leased the entirety of Uptown Station’s nearly 356,000 square feet at 1955 Broadway, the building formerly targeted by Twitter. This August, Pacific Gas and Electric Co. bought the headquarters it was formerly leasing at 300 Lakeside Drive. The $900 million sale price could net millions in real estate transfer taxes once the deal is completed in 2025—in addition to the property taxes that will be paid at its newly assessed value.

Today, with ever-shifting return-to-work policies and a new plan underway to re-envision downtown and lure developers, the long-term outlook for downtown as a hub for office work remains to be seen.

In downtown Oakland, an embrace of ‘mixed-use’ development

If the past century of business in downtown Oakland began with the department store, one might say that today’s downtown begins with the rooftop.

Jason Moody is an economist and managing partner at Economic & Planning Systems, a consulting firm that’s done research and produced economic studies for the city, most recently in 2022. According to Moody, in downtown Oakland currently, “rooftops drive retail.” In other words, the city and downtown developers have embraced “mixed-use” developments that are both residential and commercial.

Some critics of this approach point out that residential developments cost cities more than commercial developments do long-term because housing doesn’t bring sales tax revenue to the city. Also, said Moody, the “cost of providing municipal services to residents (e.g., increased public safety, park and recreation, infrastructure maintenance, etc.), is not offset by residential property taxes.”

Still, said Moody, there are parts of Oakland that show its urban neighborhoods can be a home for residents while also driving revenue. Although not situated in downtown proper, he cited changes over the past 10 years to the 3000 block of Broadway in the downtown-adjacent Pill Hill neighborhood—where there is a Sprouts grocery store, and chains like Chipotle and Starbucks—as one example of “good redevelopment,” at least from a public revenue standpoint.

Where the Sprouts is now was once a used car lot, and where an auto dealership was previously is now a mid-rise building with a Mercedes dealer on the ground floor. The increase in assessed property values, according to Moody, is over $300 million, which should result in higher property and retail tax revenue for the city.

Downtown Oakland retail vacancies are up, but so are prices

The health of downtown’s retail sector—which includes things like clothing stores, art galleries, markets, and restaurants—has been a big part of the conversation about downtown’s economic recovery, as many small businesses have struggled to rebound from the pandemic. Some local business owners, including in downtown, have also cited crime and public safety as growing concerns impacting their ability to stay afloat.

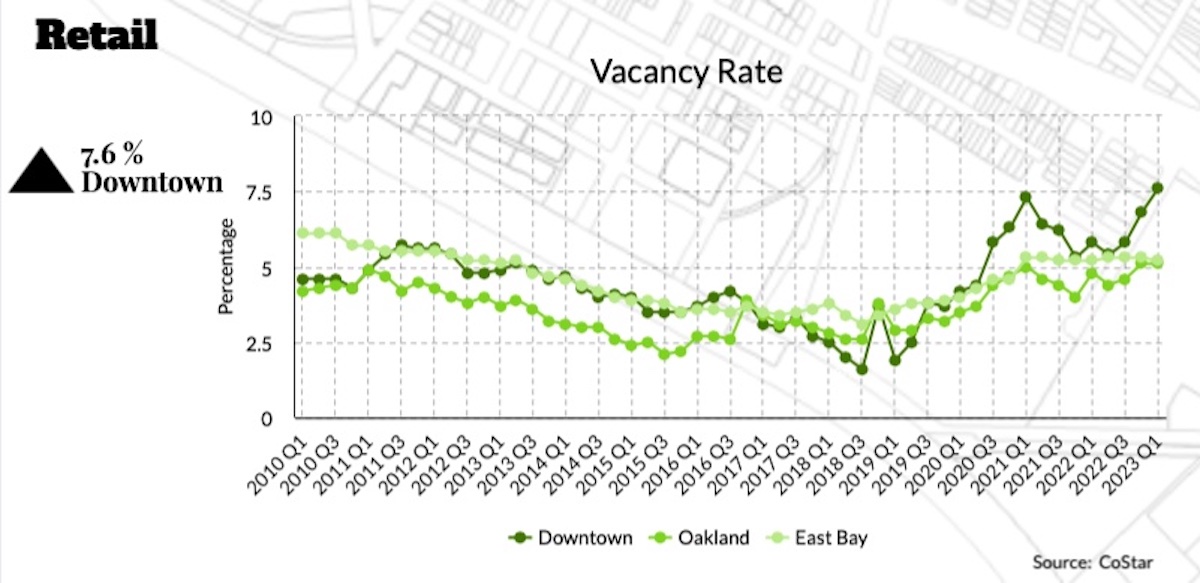

Data from the Economic Dashboard shows a fluctuating but steep spike in downtown’s retail vacancy rate between 2019 (about 2%) and today (well over 7%).

These vacancy rates might not tell the whole picture, according to Miles Dotson, co-founder and director of the Sanctuary for Sustainable Artistry. His nonprofit organization runs Micro Market Space on 977 Broadway to help small businesses operate in a brick-and-mortar space without the prohibitive overhead of rent in Oakland.

“I think those numbers are being reported less than accurately,” cautions Dotson. Property owners are responsible for self-reporting their vacancy rates and “they get to define the zone and use of the space.” In other words, a vacant storefront may not be registered or reported as such. Dotson said his organization is aware of vacancies because it conducts walking tours and unofficial on-the-ground counts.

Despite the rising number of retail vacancies downtown, the cost of renting retail space has mostly increased over the past decade-plus. At $34.36 a square foot, this year marked the first time the price had fallen since 2010—and only by a measure of 34 cents since the end of last year.

Sales tax revenue feeds into Oakland’s general fund and is another indicator of how well the local retail economy is doing. Recent sales tax reports show that Oakland has gained back some of the revenue it lost during the pandemic. According to the city’s Comprehensive Financial Report for the 2021-2022 fiscal year, sales and use taxes citywide generated 6.7% of Oakland’s total revenue—an increase of $10.4 million, or nearly 12% over the previous year, “as locally generated taxes continued to recover from pandemic-era declines.” The report did not include retail sales tax revenue numbers for downtown specifically.

The same report shows that business license taxes declined by $2.9 million, which it attributes to “reduced gross receipts from large construction projects.”

Dotson sees local retail and food businesses as integral to the local economy because they not only provide important amenities to residents but also serve visitors.

“When you only frame these businesses as an aspect of the local communities you miss out on the fact that cities are a juncture for people passing through,” he said.

Recent trends offer hope that Oakland tourism will rebound

Indeed, the business of visiting, staying, and eating in Oakland is showing promise as a strong revenue driver for the city, according to some reports. A May press release from Visit Oakland, a non-profit organization responsible for marketing Oakland, put the local value of tourism in 2022 at $784 million. Of that, it said, “lodging accounted for $194 million, 33% of total visitor spending. Food and beverage spending resulted in $155 million.” Visitor levels increased 22% from 2021 to 2022 and now stand at 83% of the city’s 2019 pre-pandemic levels.

While these figures are not isolated to downtown, there’s reason to believe the area is central to tourism. The 2022 Economic Trends and Prospects report cited several of Oakland’s downtown institutions—including the Fox Theater and Paramount Theater—as “premier event and recreation destinations.”

There’s also the smattering of downtown hotels to consider, such as the Marriott, Ramada, The Moxy in Uptown, and The Waterfront at Jack London Square. The city’s report said transient occupancy taxes from these hotels and others generated $16.7 million in 2022. While that represents an increase of 57% over the previous year, it’s still not at pre-pandemic levels, which reached $33 million in 2019.

What does the future hold for downtown Oakland’s economy?

Next year, the Oakland City Council is expected to vote on the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan (DOSP), which would have a major impact on all aspects of the area—from zoning for commercial properties and housing to artist spaces. The plan focuses on mixed-use development, like the 3000 Broadway block that Moody highlighted.

Bumps in the road may still be lurking, though. For instance, Moody suggested keeping an eye on office vacancies, since many businesses entered leases downtown before the pandemic began, and those leases will soon come due. If companies have adopted work-from-home protocols, they might not reenter into their leases, which could negatively impact the market downtown.

But more mixed-use development is almost certainly on the way, said Moody, with new legislation like AB-2011, a California housing and jobs act that will allow for more residential development in cities. As a result, he said, areas like 3000 Broadway and parts of downtown Oakland could be a microcosm of more “intense and vibrant” development to come, where residents have nearby access to retail and restaurants.

Dotson said that downtown Oakland and other urban centers are in the midst of an important transition. “We’re moving into a social and creative era of cities,” he said. “Cities need to be built more like theme parks with social amenities and attractions that garner long-term life.”