Since 2015, the city of Oakland has been hashing out the details of a massive plan meant to guide future development and revamp downtown—and it could be landing in front of the City Council for approval as soon as early next year.

The Oaklandside is partnering with Oakland North and Oakland Lowdown to examine what’s working well and what isn’t for people in our urban center. Read more.

Illustration by Bea Hayward

In broad strokes, the “Downtown Oakland Specific Plan” provides a vision and roadmap for making a large swath of Oakland’s urban center a thriving residential and business corridor—one that’s accessible, affordable, and maintains downtown Oakland as a hub for art and culture, among other stated goals.

The 342-page document has the potential to influence how and where housing, businesses, and public space in downtown Oakland grow over the next 20 years. But the sheer size of the plan and the depth of detail it contains make it unlikely that most Oakland residents will have the time or the patience to understand what it contains and how it might impact their lives.

So we set out to do the heavy lifting for you. We spent hours pouring over the draft plan and talking to experts so we could better understand it. This article isn’t intended to be an in-the-weeds breakdown, but rather an overview sharing some of our high-level takeaways with readers, with some historical context. We also know that any development plan of this scale is going to have its critics, and this one hasn’t been without controversy. We’ll be doing more reporting in the coming weeks to understand some of the concerns around big development projects downtown.

What areas of downtown Oakland are included, and what is the plan meant to do?

The Downtown Oakland Specific Plan is one of nine neighborhood-specific plans that have been created by the city of Oakland, each setting forth a vision for making their respective areas more “sustainable and vibrant” for residents, businesses, and visitors.

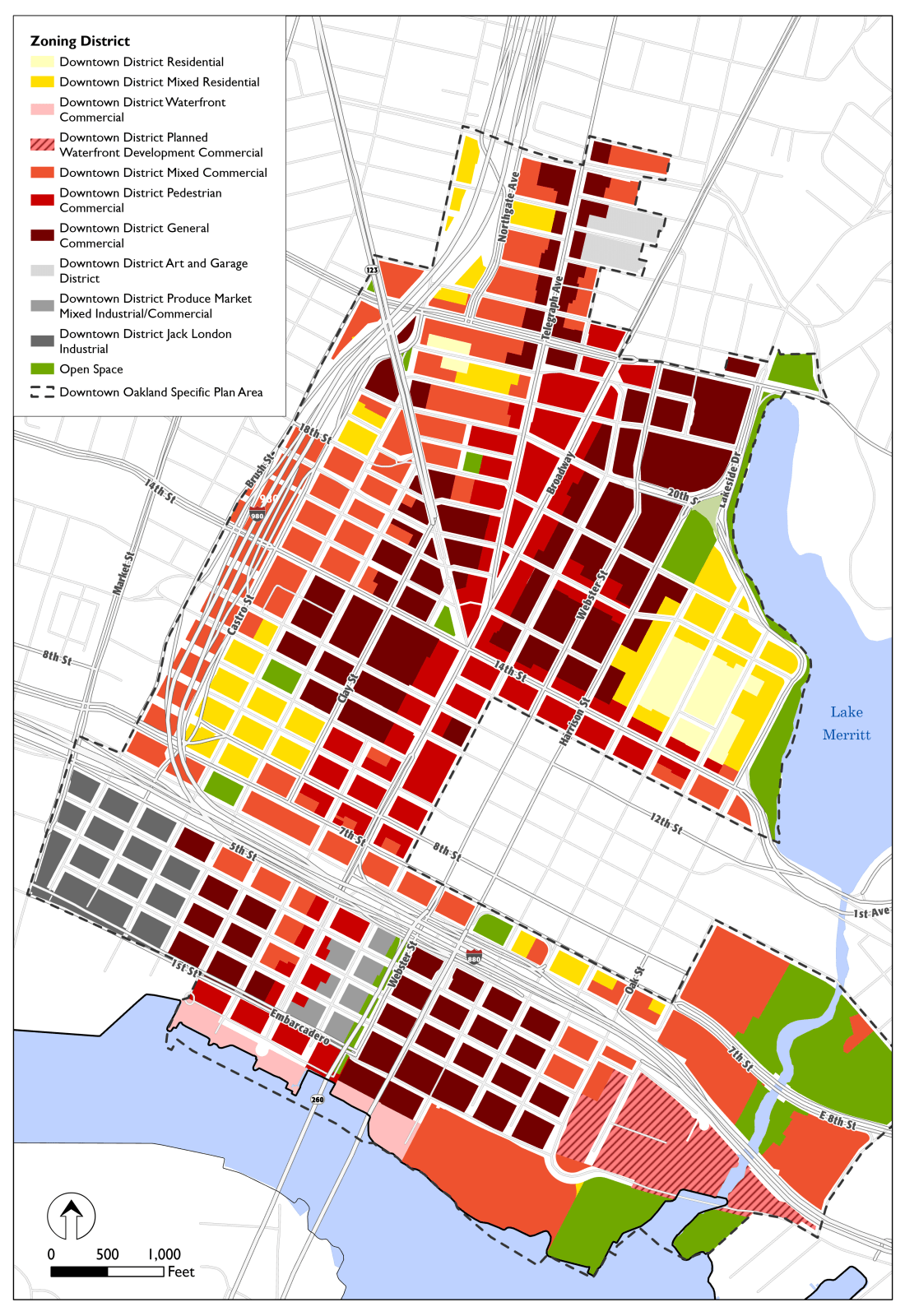

The plan defines downtown as the neighborhoods and commercial areas that include the Jack London District in the south up to 27th Street in the Koreatown-Northgate neighborhood, and from I-980 on its western boundary to Lake Merritt. One neighborhood that’s not included is Chinatown, which was already folded into the Lake Merritt Station Area Plan, which was completed prior to the start of the downtown plan.

The downtown plan focuses on six areas: housing, economic opportunity, mobility, culture, community health, and land use—each of which is explained in more detail below. The plan also weaves racial equity throughout these core tenets. For example, the plan calls for the creation of a downtown cultural district meant to foster and protect Black-owned businesses.

Some of the main things the plan aims to do are change downtown’s zoning regulations to allow developers to build taller, denser housing near transit hubs; grow Oakland’s economy and tax base by stimulating new business and charging developer impact fees to fund public services and community benefit projects citywide; improve access to and connections between downtown’s neighborhoods; and make it easier for arts and entertainment venues to get the necessary permits for live events.

More than eight years after work began on the expansive plan, however, Oakland City Council has yet to vote on it. Joanna Winter, the plan’s project manager with the city’s Strategic Planning Division, said during a community meeting in June that it could soon come before the council. “Some people thought it was already adopted,” said Winter. “But no, it’s still in progress. We are hoping to adopt it later this year.”

Contacted by The Oaklandside, Winter provided an update for that timeline, saying the plan has not yet been put on the council’s agenda, and that it’s now more likely that any discussions about adopting the plan won’t happen until next year.

The downtown plan aims to balance economic development with equity

Over the past 50 years, Oakland has tried several times to reimagine and transform downtown and other parts of the city, and echoes of those plans still reverberate in the language of the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan and other current development projects.

Oakland’s Redevelopment Agency, which operated from 1956 until early 2012, embraced one such program in the 1970s called “Patterns of Growth,” with a mission “to create a balanced urban environment that benefits all the people of Oakland.” Similar to the city’s current plan for downtown, it advocated for a “strong commitment” to housing for low-to-medium-income residents and to “providing for the social, economic and racial integration of Oakland.”

But the most recent comprehensive rehabilitation strategy for downtown was spearheaded by former Oakland Mayor Jerry Brown, who proposed bringing 10,000 new residents to downtown Oakland. With the help of some wealthy developers, and within a few years of him starting his first term in 1999, the city was close to creating the 6,000 new units needed to fulfill the mayor’s “10k Initiative.”

Much of downtown is characterized as undergoing ongoing gentrification/displacement.

Oakland Planning & Building Department, April 2018 report

Brown’s plan put a large focus on market-rate housing and transitioning much of the city’s vacant industrial buildings into live-work lofts—he even lived in a Jack London District warehouse and later the old Sears building on Telegraph Avenue. There was concern then about people of color being displaced in the process, but Brown was dismissive of these and referred to critics of his plan as a “negative cheering section” at the time.

“They got a name for it,” Brown quipped in a 2001 KQED documentary. “They call it ‘gentrification.”

In the ensuing years, economic displacement is just what occurred in Oakland—in downtown and many other parts of the city—as Bay Area housing costs soared and economic inequality grew, particularly following the Great Recession of 2008.

Studies of downtown Oakland conducted by the city in recent years have verified this trend. Using a “gentrification index” developed by researchers at UC Berkeley, the city’s Planning and Building Department concluded in 2018 that “much of downtown is characterized as undergoing ongoing gentrification/displacement.”

Early on in the planning process for the current Downtown Oakland Specific Plan, according to Winter, community members during public meetings expressed concerns that the city again wasn’t doing enough to take racial equity or the needs of Oakaland’s artist community into account, to avoid displacing people of color from downtown.

Work on the plan was paused in 2017 while the city created a Department of Race and Equity. The city hired a racial equity advisor, did more community outreach, and took into account disparities facing downtown residents when it comes to things like the cost of housing, homelessness, displacement, unemployment, access to youth services, and income. Many of these challenges were only exacerbated by the pandemic.

After several years of meetings with community stakeholders, in August 2019, the city released a revised 342-page plan for downtown.

Savlan Hauser—executive director of the nonprofit Jack London Improvement District, a collection of business owners in the area—said the new document reflects certain aspects of Jerry Brown’s vision 25 years ago, though it also acknowledges the importance of equity for vulnerable communities in a way that the 10k Initiative did not.

“Development language has evolved a lot since then,” Hauser said of the late ‘90s and early 2000s. “Careful planning and community engagement create the balance.”

Denser housing in exchange for community benefits

With any urban blueprint as far-reaching as the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan, said Hauser, “you have to plan years ahead to stay relevant.”

That was impossible with the downtown plan, however. City planners and officials couldn’t foresee the massive changes that would occur mere months after releasing their draft. In spring 2020, the pandemic led health officials to order shutdowns of local businesses. Customers disappeared, restaurants closed, and offices emptied out of workers. The pandemic also worsened Oakland’s homelessness crisis, leading more people to become unhoused and making it more difficult to help them.

If there was a silver lining, said Hauser, it’s that while the pandemic laid bare many inequalities for people living in Oakland, it also showed that dense neighborhoods with amenities fared better during the crisis overall. Areas that were merely job centers, on the other hand, were quickly vacated and have had a more difficult time recovering.

The new downtown plan seeks to bring more of the former—denser housing and amenities for residents—to downtown Oakland.

In total, the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan anticipates 29,100 new housing units within the next two decades, including more than 7,200 affordable units. The plan proposes making way for some of this new housing by demolishing I-980, the freeway that separates downtown from West Oakland. The plan also encourages new housing around the 19th Street and Lake Merritt BART stations, to situate more residents near mass transit.

The plan also places an emphasis on zones for “mixed-use” developments, meaning new constructions that are a combination of residential and commercial space. It remains to be seen what these buildings might look like, but some of the recent mixed-use developments around Oakland BART stations and Lake Merritt—referred to in the plan as “Central Core” developments—offer a glimpse of what these buildings might look like.

But while the city can build some infrastructure and create policies to guide development, said Winter, the plan’s success will rely largely on what downtown property owners and private developers choose to do. Winter is optimistic that if the plan is approved, it will help draw investors to downtown.

“We have heard from many developers that they are interested in proposing projects once the DOSP and its zoning amendments are passed,” Winter told the Oaklandside.

One of those amendments is the Zoning Incentive Program, where developers can choose to either pay a fee or include on-site community benefits in their projects—things like affordable housing, below-market-rate commercial space, or streetscape improvements—in exchange for being allowed to build higher, more dense housing.

If a developer chooses to pay the fee, then the revenue would be used to fund job-training programs. If they choose on-site community benefits, the downtown plan stipulates that those must include the provision of public restrooms—something that’s currently absent from downtown.

The Zoning Incentive Program is one aspect of the downtown plan that could face scrutiny when it does eventually reach the City Council. In a May 2023 presentation to the city’s planning commission, city staff noted that community members criticized the program for being too complicated and confusing while not promising enough affordable housing to meet the area’s needs.

New housing at Victory Court would connect Jack London and Brooklyn Basin on Oakland’s waterfront

Under the plan, more than 20% of downtown’s new housing over the next 20 years would be built in a small geographic area surrounding Victory Court, a dead-end street lined with tall eucalyptus trees that leads up to the Oakland Fire Department’s training facility, a tower that’s easily recognizable from I-80. The same plot of land was considered a potential home for a new A’s ballpark more than a decade ago. Besides OFD’s training facility, Victory Court is also home to single-story buildings including the Extra Space Storage facility, a restaurant supply company, and Peerless Coffee and Tea, which fills the area with the warm aroma of roasting coffee beans.

Building new housing and amenities in this stretch of Oakland’s waterfront—much of which Hauser of the Jack London Improvement District said currently “feels like a wasteland”—would serve to connect Jack London Square and Brooklyn Basin, two neighborhoods that have seen rapid growth of their own in recent years.

Victory Court is emblematic of the downtown plan’s general approach to housing development: getting the most out of underutilized land by proposing dense residential developments on smaller plots. In all, the plan calls for roughly 6,000 units to be built at the unassuming Victory Court, along with 850,000 square feet of commercial development—550,000 for offices and 300,000 for retail shops.

To support the movement of new residents, workers, and shoppers in and out of the area, the city’s plan includes improved connections to and from Brooklyn Basin, Jack London Square, Lake Merritt, and BART stations through strategies like protected bike lanes, better use of open space, and a pass-through to 3rd Street for emergency vehicles.

The plan also cites the potential for Oakland to adopt building regulations on physical accessibility for all Oaklanders. Alameda’s enactment of universal residential designs, so that potential disabled residents can access new developments, is cited as an example.

Economic opportunity, ‘culture-keeping,’ and community health

A number of elements in the plan were included to address equity concerns and promote economic and cultural diversity downtown.

Some of the zoning changes in the downtown plan that are meant to decrease the distance between Oaklanders’ homes and workplaces, for example, would allow some tenants to lease ground-floor storefronts at more affordable rates.

This proximity could also have public safety benefits: With more Oaklanders out and about, city planners predict the added foot traffic could prevent some crime in the area.

The establishment of “youth empowerment zones” would provide career and professional development—with an emphasis on business and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) jobs—to underserved young people, and these efforts would be coordinated in partnership with local nonprofits.

The plan also aims to establish more “maker spaces,” or publicly accessible places where residents can work on collaborative projects with equipment that’s too expensive for the average person to keep in their garage. Current maker spaces—like Port Workspaces in Uptown and Jack London Square—would be preserved and not displaced by new ones under the downtown plan.

Downtown Oakland’s history would be celebrated through the use of public markers and art displays, although the plan doesn’t offer specific examples of what areas or aspects of downtown’s history would be honored or memorialized.

When it comes to entertainment, the plan includes measures meant to alleviate the frustrations of some downtown event promoters and venue owners over government red tape and difficulties navigating the city’s permitting process. Among the recommendations is a user-friendly website for event planners to apply for permits and other planning documents from the city, and the creation of special zones downtown that wouldn’t require an event permit.

The plan also discusses the potential for new city codes to allow for things like pop-up events, public art installations, and new cultural district zones more easily.

Specifically, the plan supports the continued development of a Black Arts Movement and Business District along 14th Street from Oak Street downtown to Frontage Road in West Oakland—first established in 2016—with public art, signage, and storefronts, along with “special urban design elements and marketing materials.”

While the downtown plan calls for the Black Arts Movement and Business District to create its own plan—which could include a master lease program—it does suggest street improvements, like wider sidewalks and custom bike lanes, as well as a “pocket plaza” to host artists and musicians.

Dover, Kohl & Partners—the Florida-based planning firm the city hired to help create the downtown plan—emphasized the potential benefits of activating public parks and open spaces for art and community events. The combination of permanent housing for unsheltered residents and allowing temporary pop-ups and vendors in public spaces, they wrote—without the need for permits from the city—could help improve the quality of Oakland’s parks and provide more “‘eyes on the street,’ which may also have the added benefit of reducing crime and vandalism.”

The plan recommends “incentives to encourage childcare facilities throughout downtown Oakland,” although few details are provided, along with “partnerships with educational institutions to provide more targeted job training centers.”

What’s next for the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan?

While the city doesn’t currently have any public meetings listed on its Downtown Oakland Specific Plan website, Winter said city staff hopes to start adoption hearings by the end of the year, but “anticipate that they may run into 2024.”

Those hearings would begin with the Planning Commission, which must approve the plan before the plan goes before the City Council for a vote. If adopted, it will be up to developers at that point to make the next moves.

“We expect that as soon as market conditions pick up, developers will be interested in leveraging the benefits provided by the DOSP,” Winter said.

For Hauser, watching the plan be developed over the past several years has felt “like studying for an exam and never taking it.” She’s excited to see the city’s plans for downtown finally come to fruition.

“Downtowns are not going anywhere,” she said. “This is where our cultural and economic lives center around. The quiet we may see today is temporary.”

Illustration of downtown Oakland by Bea Hayward