Journalist William Gee Wong will launch his new book, “Sons of Chinatown: A Memoir Rooted in China and America” on Mar. 24, just blocks from where the author was born.

Wong, 82, a longtime journalist—dubbing himself “yellow journalist”—became prominent locally and nationally as one of the few columnists writing about Chinese American identity and Asian American issues in a mainstream newspaper at the time.

Sons of Chinatown: A Memoir Rooted in China and America

William Wong will launch his book on Sunday, Mar. 24 at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center. Wong will be in conversation with Harvey Dong, co-founder of Eastwind Books. Eastwind Books will also be selling the memoir at the event, or they be purchased online.

Wong spent decades writing about news, businesses, and Chinese American communities and Asian American stories, mostly for mainstream newspapers such as the SF Chronicle, The Wall Street Journal, and the Oakland Tribune. In 2022, the Society of Professional Journalists Northern California chapter honored Wong with a Career Achievement Award.

Now, he turns his storytelling to his family’s past, from his father’s immigration during the Chinese Exclusion Act, to Wong’s childhood in Oakland Chinatown, to his career as a journalist, and the meaning of place, identity, and culture.

“Rooted in Chinatown”

Wong’s father immigrated to the U.S. in 1912 as a teenager from Toisan in Southern China. As a “paper son,” Wong’s father, who he refers to as “Pop,” came to the U.S. pretending to be the son of a U.S.-born man.

After the 1906 earthquake and fire, which burned down all of the records in San Francisco City Hall, including birth certificates, “paper son” was a common way that Chinese boys and men immigrated to the U.S. The year 1912 was during the Chinese Exclusion Act, which almost completely barred immigration for Chinese people unless they had familial ties in the United States.

Wong explains the book title refers to both himself and his father as the “sons” of Chinatown. “In a metaphorical sense, he and I are both sons of Chinatown,” Wong said. “He was, legally, a son of a native, which got him in.”

Wong was born in 1941 on Harrison street between 7th and 8th in Oakland Chinatown. His early childhood years were rooted in this tight-knit, ethnic enclave.

“It was like extended family because my family was like a lot of other Chinatown families from generally the same region [in China], with some Cantonese and some Hoisan-wa speakers,” Wong said, referring to the Toisanese language.

He remembers other families with shops—Wong’s parents were also entrepreneurs, owning a restaurant called Great China on Webster Street (now Imperial Soup).

“There was a live chicken and duck store on 8th and Webster, herb shops, restaurants, laundries. It was a really small and almost homogenous community with families with children of about the same age group.”

Within a few square blocks, a sense of safety and community was felt. Wong attended Lincoln Elementary School, just like the other kids in the area, and played at the rec center. “Chinatown was my universe. The streets of Chinatown were our playground. Lincoln school was our American unifying institution where we all learned English and played together at Lincoln Square.”

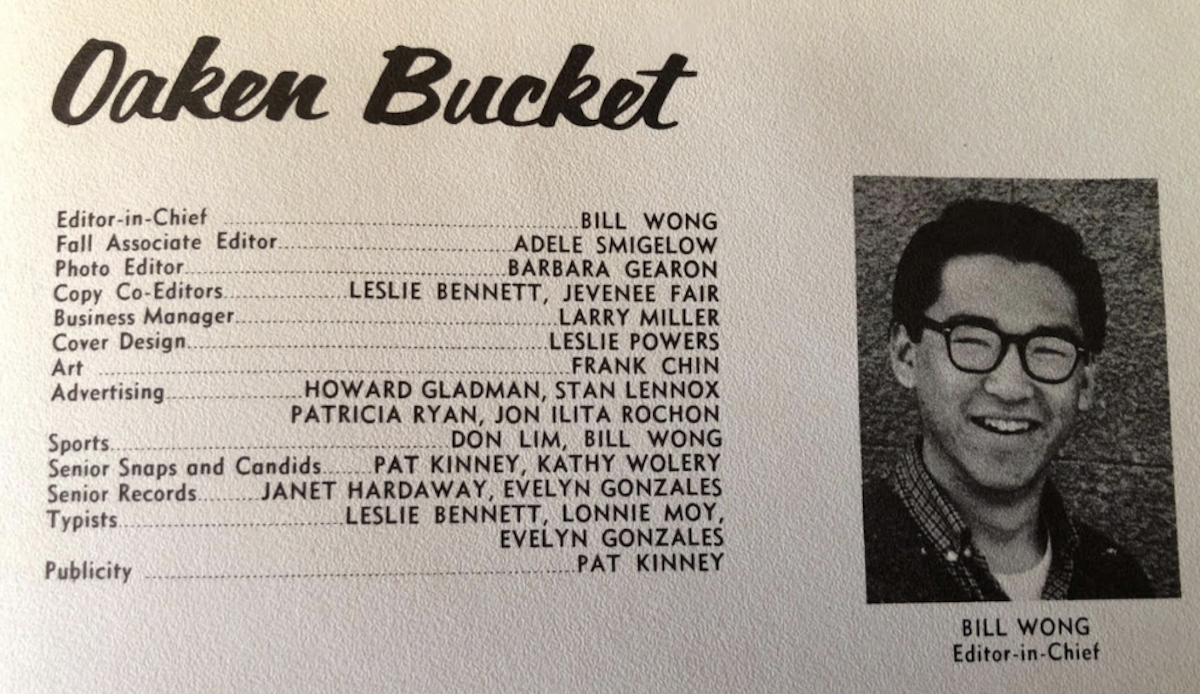

Wong’s early days as a reporter and editor, including at Oakland High’s newspaper

Growing up in Oakland Chinatown, Wong said he loved to play sports. In the late 40s, Wong began listening to Cal football games on the radio. He avidly followed American sports – basketball, baseball, and football – and also read the Oakland Tribune sports pages.

At Oakland High, Wong tried out for sports teams but didn’t make the cut. “Once I knew I wasn’t going to be an athlete, I said, ‘What’s the next best thing?’” It turns out it was writing about sports for the school paper, the Aegis, at Oakland High.

Wong attended UC Berkeley, and became the sports editor of the Daily Cal, the student newspaper, and then eventually became editor-in-chief for a semester in 1962. He later worked for the San Francisco Chronicle and moved to the San Leandro Morning News. Later, he moved to the San Francisco News Call Bulletin.

He took a break from writing and joined the Peace Corps program in the Philippines in ‘64. He decided to go back to school, at the Columbia Journalism School. Right after grad school, he landed a job in Cleveland working for a Wall Street Journal bureau. He returned to the Bay Area in 1972 to work at the S.F. bureau of the Wall Street Journal.

Asian American community stories

Wong returned to the Bay Area during a time of social movements and identity formation and change. “I had a period of rediscovery,” Wong reflected. Wong points to the Asian American movement of the late 60s, when Asian American studies programs were founded at both S.F. State and UC Berkeley, as big changing points.

When he worked at the S.F. bureau of the Wall Street Journal, his office was close to Chinatown. There, he learned about East-West, a bilingual Chinese American weekly.

At the same time, the Wall Street Journal encouraged Wong to come up with enterprise feature stories. “I knew I had an opportunity to both learn about this growing Asian American movement, and perhaps write about it occasionally for the Wall Street Journal.”

Wong estimates he published 6-8 major feature stories on the front pages of the Wall Street Journal, including a profile of the newly-formed Chinese for Affirmative Action, one of the first Asian American civil rights organizations post-WWII. Wong also wrote for East-West and AsianWeek, which was published by the Fang family in San Francisco and now-former owners of the SF Examiner.

While most of Wong’s writing was focused on business and other topics, Wong said that covering Asian American issues was “the proudest journalism moments for me.”

Back to Oakland at the Oakland Tribune

As a seasoned journalist by the late 70s, Wong was a part of a work reduction at the Wall Street Journal after nine years of working there. Around the same time, he had met Robert Maynard, then the editor-in-chief of The Oakland Tribune. Wong contacted Maynard, asking if there was a spot for him at his hometown paper. “I said I just wanted to write, and I was specific I wanted to write about Chinatown and Asian American stuff,” Wong said.

Maynard initially hired Wong as a business editor and was later promoted to assistant managing editor, which meant that writing took a backseat. “At the time, it was a pretty big deal for a Chinese American journalist like me from Chinatown,” Wong said. Wong saw his placement at The Tribune as part of the newspaper industry’s efforts to integrate more journalists of color into mainstream newspapers. Wong later became the paper’s ombudsman from 1984 to 1986. “That reignited both my desire to be a writer and to marry that with my continuously evolving search for my racial and ethnic identity.”

Robert (“Bob”) and his wife Nancy Maynard became the publishers of the Oakland Tribune, the first time a Black publisher ran a major U.S. newspaper. “Maynard was an extremely important figure in my journalism career, because he gave me several opportunities I might not have gotten if I worked at a newspaper owned by white people,” Wong said, referring to Bob Maynard.

Through Wong’s columns at the Oakland Tribune, he developed an audience and reputation for his commentary on identity, race, and stories that highlighted Asian American issues and Chinatown.

In 1992, Bob Maynard sold the paper, and new editors were brought in. In March of 1996, Wong was let go. He was told that the position was being downsized, but he was the solo staff person who was let go that day. Wong alleges it was a firing, and an unjust one. Wong’s departure from the Oakland Tribune led to public outcry, including support from former CA governor Jerry Brown, who lived in Oakland at the time (Brown later became mayor of Oakland for 8 years).

Wong insists that the cut was personal. He was one of the few Asian American columnists in the nation, writing about Asian American issues.

Post-Oakland Tribune

After the Tribune, Wong stayed busy. He wrote a book, “Yellow Journalist: Dispatches from Asian America,” was published in 2001 by Temple University Press. Wong continued to work on freelance writing and other projects, but he never returned to full-time journalism.

Wong’s memoir was initially sparked by the desire to connect with his children and grandchildren, and for them to learn about their family history. He showed an early draft to his son and daughter-in-law, who then asked, “Where are you? They wanted to hear more about me,” Wong said. In the last 13 years, Wong continued to write, re-write, and edit his memoir.

Wong said he is happy his memoir is finally completed. “I simply would like people to read it and get the message,” he said.