Theaters of various sorts have entertained people in downtown Oakland since the city’s earliest days. In the mid-to-late 19th century, they attracted crowds with live plays and vaudeville productions that often included comedy, burlesque, and dance. But the turn of the 20th century brought a bright new attraction to the town’s theaters: motion pictures.

The Oaklandside is partnering with Oakland North and Oakland Lowdown to examine what’s working well and what isn’t for people in our urban center. Read more.

Illustration by Bea Hayward

Early cinema sparked the fascination of Oaklanders. Older theaters adapted to accommodate films, and new movie houses sprang up around town. By the 1940s, coinciding with a post-war American filmmaking boom, Oakland’s movie theaters had reached peak popularity, with dozens across the city, many of them downtown.

But some 80 years later, downtown’s movie scene couldn’t be more different. In fact, Oakland as a whole currently has only a small handful of movie theaters: Landmark’s Piedmont Theatre (founded in 1917, it’s the oldest operating motion picture house in Oakland), the historic 1920s-era Grand Lake Theater, the New Parkway Theater, and Regal’s Jack London Cinema, the only theater remaining in the greater downtown area. Two other prominent downtown venues, the historic Paramount and Fox theaters, host performances but no longer screen films.

So, what happened to downtown Oakland’s once-thriving theater scene? We set out to learn more by digging through archival records at the Oakland History Center, combing through newspaper articles dating back to 1874, researching the pages of Oakland Wiki, and reading the book Theatres of Oakland by Jack Tillmany and Jennifer Dowling.

Before movies, Oakland’s theaters were alive with stage plays and burlesque

In December 1895, French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière held the first public motion picture screening in Paris. Six years later, Oakland showed its first “moving picture” at Peck’s Broadway Theatre on Broadway and 13th Street.

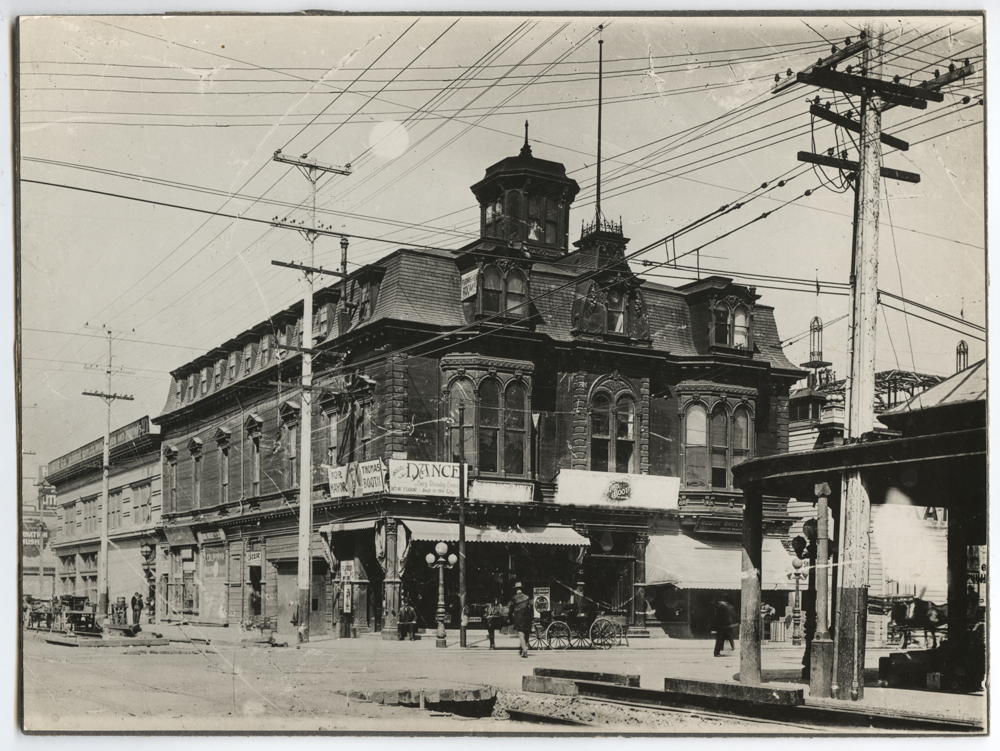

But the first theater in Oakland to show movies regularly was the Dietz Opera House on 12th and Webster streets, which operated from 1875 until it shuttered in 1905. A few doors down, the Dewey Theatre was famous for its “vaudeville” shows, a type of entertainment that included comedy, burlesque, and dance. In 1911, both venues burned to the ground, leaving behind a prized piece of real estate that would turn into commercial buildings years later.

Despite the fiery loss, over the next four decades, Oakland’s movie-going audience exploded, and the city became home to dozens of movie theaters, many located downtown.

The golden era of movie theaters in Oakland

In the 1940s, Oakland was home to 49 theaters. The two largest were the Fox and the Paramount, “larger than any on the West Coast, except for San Francisco’s Fabled Fox,” according to an excerpt from the book Theatres of Oakland.

During the war, Oakland operated as a 24-hour city, and many theaters offered showings all day and night to cater to military service members, workers, and residents. Audiences were offered more than just a film; many theaters showed animated shorts, newsreels, and live-action short comedies to accompany the featured programming. Theaters competed with dance halls, arcades, bowling alleys, and other types of entertainment, giving service members discounts. Although they were never utilized, the theaters downtown were among some buildings that served the war effort as emergency air-raid shelters.

The post-WWII economic boom ensured the theaters’ continued success, but as televisions became common household items, many failed to keep audiences. Some shifted to screening foreign or adult films, like the Turner & Dahnken’s Circuit’s T&D Theatre—colloquially known as the “Tough & Dirty”—which opened in 1916 at 429 11th Street. While T&D tried to remain relevant by offering screenings of live sporting events, it eventually shuttered in 1973 and was razed in 1979. In the years since, the address was changed to 1000 Broadway, home of the Trans-Pacific Centre.

The original Fox Theatre opened in 1923 at 1730 Broadway. It was later renamed the Orpheum and remained in operation until 1952. The building was demolished in 1967.

The current Fox Oakland opened in 1928 at 1819 Telegraph Ave. It shuttered in 1966 when many businesses—theaters, department stores, and others—were leaving downtown. Nonetheless, the Art Deco and Middle Eastern-inspired theater became a city landmark in 1978 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The city of Oakland purchased the building in 1996, and it reopened in 2009 after extensive renovations totaling $75 million.

The Dufwin Theater was opened in 1928 at 517 17 Street by Henry Duffy and his wife, actress Dale Winter. Together, they had a theatre troupe called the Henry Duffy Players and ran about a dozen theaters on the West Coast. In the late 1930s, it reopened as the Roxie Theater and operated until the early 1980s.

In 1930, as the country dealt with the start of the Great Depression, a yearlong project by Paramount Publix Corporation—the theater division of Paramount Pictures that went on to build many other theaters across the county—promising to boost the local economy and employ hundreds of workers, from builders and plumbers to steelworkers and carpenters—broke ground. As a result, on Dec. 16, 1931, the Paramount Theatre, Oakland’s largest art deco movie palace, opened its doors.

When BART broke ground and began construction in Oakland in 1966, it greatly disrupted the Paramount’s operations. Increasing crime rates at the time also put the theatre in a dire position. The last screening of a mainstream film at the Paramount took place in 1970. The famous marquee wouldn’t be lit up again until 1972 when the Oakland East Bay Symphony purchased and renovated the theater. The Paramount has been a city, state, and national historic landmark since the 1970s. Until the pandemic in 2020, the theatre hosted a Paramount Movie Classics night with screenings of 35mm film prints and old-school newsreels.

The Beaux-Arts-style Grand Lake Theatre, designed by the Reid Brothers architect firm, opened its doors in 1926. Reid Brothers was also commissioned to design the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. The original Grand Lake Theatre had its box office outside, and the marquee was shorter than the one we see today, installed in 1937. When it first opened, the theatre only had one auditorium, including retail space. In 1981, what was the balcony of the original auditorium became a second-floor auditorium. That same year, the building was also designated as an Oakland Landmark. The theater’s third and fourth auditoriums were added in 1985. Today, the Grand Lake is still a popular destination for Oakland movie-goers, and its marquee can often be seen sporting politically aware messages.

The rise of TV and the decline of movie theaters in Oakland

By the early 1950s, the rise in popularity of TV disrupted the attendance to theaters nationwide. Americans no longer had to go to the theater for nightly news programming or casual entertainment. In Oakland, many theaters were razed to give way to downtown urban development. Most of those remaining were repurposed as offices, apartments, and churches.

Hollywood studios and movie theaters were forced to adapt to retain audiences, leading to the advent of “blockbuster” movies in the 1970s. Beginning famously with Steven Spieldberg’s Jaws in 1975, this new style of large-budget studio-produced films made massive profits in ticket and concession sales.

But despite these changes in the movie industry, by the late 1980s, downtown Oakland was down to two theaters—the Fox and the Paramount—after having had 17 during the peak years of the 1940s. After it closed in 1983, The Roxie became an office building, although the original tile murals were restored and preserved and can still be seen today. The architectural firm Weeks and Day designed the building’s facade and was commissioned to work on downtown Oakland’s I. Magnin Building and the Fox Theatre.

The current state of theaters in downtown Oakland

The advent of the Hollywood blockbuster coincided with changes in the movie theater business, with many independent urban theaters being replaced by multiplex chain theaters—often in the suburbs—which could show more films and often host larger audiences.

The Jack London Cinema opened as Oakland’s first multiplex in 1973 at 201 Broadway. It didn’t gain traction with moviegoers, though, and transitioned into an adult venue renamed Xanadu, then Secrets. The adult-film theater operated until 2016 and was demolished in 2023.

Jack London Cinema reopened near its original location at 100 Washington Street in 1995. It remains the only operating theatre in Oakland built since the Paramount in the 1930s. Since reopening after the pandemic, the theatre eliminated box office attendants and switched to automated ticket machines.

While Jack London Cinema stands alone downtown, it may not be the sole downtown movie theater in the years to come. Oakland film professionals remain committed to building the industry in the city in a campaign that has gained the support of the mayor. This could signal the return of movie screenings, film festivals, and premieres at some point in downtown’s future.