As a child, Jim Covel always saw the Rotary Nature Center at Lake Merritt as his second home. In turn, his home was a second nature center. Jim’s father, Paul Covel, was the first municipal park naturalist ever appointed to the first wildlife refuge in North America. At the time, there was no place like it in any urban area across the nation. Oaklanders would take injured and orphaned wildlife to the center and Paul Covel, having nowhere else to take them when he clocked out of work, would bring them home.

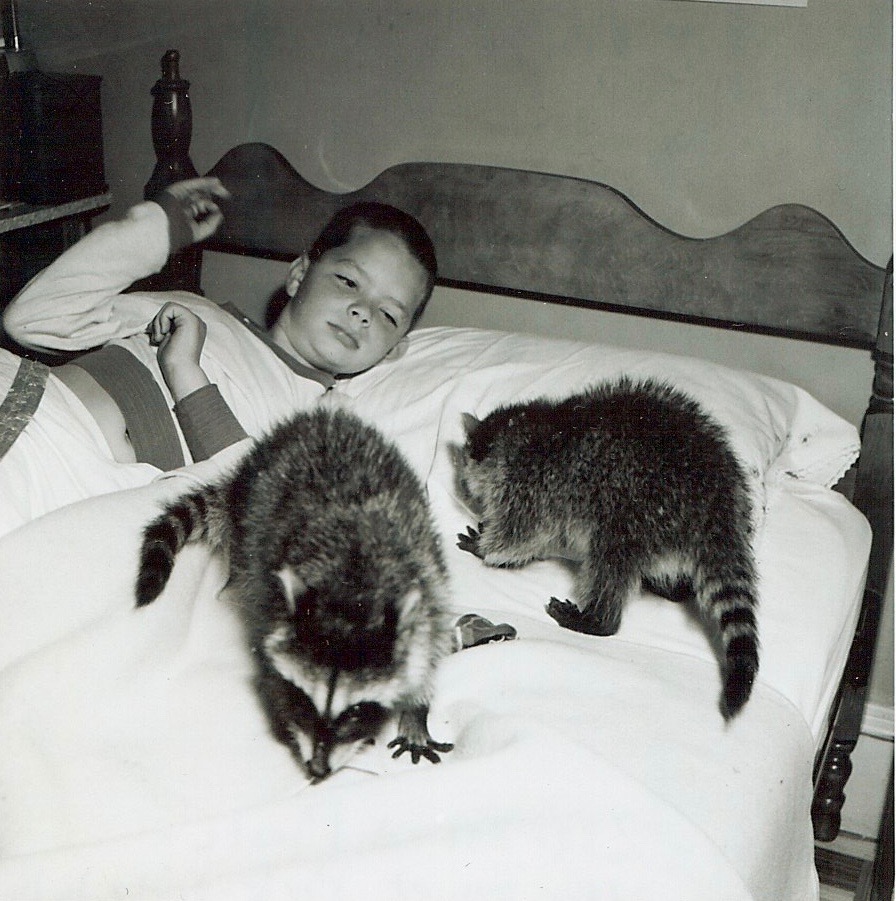

“My dad couldn’t just leave them at 5 o’clock when he locked up the nature center, these things came home with him,” said Covel. “Our home was full. Every spring we’d have raccoons and opossums, and we often had fawns. Oh! We had Gus the porcupine. We had all kinds of animals. And then birds. So many small birds—they were all orphans—that lived in our basement, in our garage, in our backyard, in the back laundry porch.”

Covel spent much of his childhood caring for these animals at home. As he got older, he started helping out around the center too. He remembers there were “a whole cadre of teens” that would lend a hand. But even back then the center required more work than just a handful of young volunteers could provide.

When the Rotary Nature Center opened in 1953, then called the Rotary Nature Science Center, it was flush with resources and funding which brought the unique wildlife oasis to life. From its inception, the center, located at 600 Bellevue Avenue in Lakeside Park, drew crowds of Oakland residents wanting to learn about and steward the city’s wildlife, especially around Lake Merritt. Within a few years of its opening, the center’s programming exploded. There were educational talks, exhibits, and activities. Schools brought students there every day of the week on field trips. The center’s team of naturalists expanded, and the center hired more staff to keep it running.

But the Rotary Nature Center’s heyday is long past. Seventy years after it first opened, the center has seen its budget dwindle. The once thriving institution is now supported by a handful of dedicated community members, several city staffers, and a small non-profit, Community for Lake Merritt. Its doors closed years ago for what many thought would be a brief period of time. But after almost six years—with only one year of opening in between—the center remains shut to the community.

A recent fire scorched the outside wall and a portion of the roof, which left the cash-strapped organization fighting once again to reopen its doors. While the damage was relatively minimal, it delayed the center’s already drawn-out reopening. The center’s leaders say the repairs will take around six months.

In the meantime, frustrations continue to grow. Community members eagerly wait for its return and reminisce on the history of the once-prosperous center. Those who’ve worked and volunteered at the Rotary Nature Center say it is a treasure that’s been neglected for too long. Many have grown tired of watching the building and its surroundings deteriorate and are pushing the city to make investments and reopen its doors to the community.

The first of its kind, revealing the wild within the city

When Paul Covel moved to the Bay Area from the East Coast in the late 1940s he brought with him a love of the outdoors. A naturalist who’d worked as a zoo bird keeper and museum collector, Covel began volunteering at Lakeside Park where he met Brighton “Bugs” Cain. Cain was a local entomologist who was employed as a naturalist by the Boy Scouts for America. Cain, seeing their shared love for outdoor education, took Covel under his wing. He even paid Covel to help him cultivate specimens for his personal collection. Around the same time, Covel met William “Bill” Penn Mott, Jr., the superintendent of parks for the city of Oakland. Together, the three of them were key figures in the Oakland parks and wildlife scene at the time.

When Cain died suddenly in 1951, there were cries from those who loved and admired him to find a way to honor his legacy. As a result, with money from the Rotary Club, the city of Oakland, and help from local community members, the Rotary Nature Center was created.

“I’ve always seen the Rotary Nature Center as Oakland’s gift to itself because it came from so many parts of the community,” Jim Covel said.

The center started with Paul Covel as its lone staff member. At first, Covel had nothing more than an old gardener’s shack in Lakeside Park to work out of. But once the official center was built in 1953, it was filled with educational materials, taxidermied animals, and specimen collections. The small green and brown building sat near the water’s edge, where community members could closely observe the lake’s array of birds and wildlife. Inside, dozens of rescued animals made themselves at home.

In 1961, as more orphaned and injured animals started being taken to the center, the city hired Rex Burress to become its first animal keeper and migratory waterfowl manager. He would later become a head naturalist there as well. Buress was passionate about sharing the beauty of nature—especially nature that appeared in an urban setting.

Not only was the Rotary Nature Center the first of its kind, but its very existence was a stark contrast to what many thought a natural park could be. The integration of city life and the natural environment was at the core of the center from its inception. The Rotary Nature Center and Lake Merritt as a whole have been a refuge for Oakland residents wanting to escape the claustrophobia of city life. But the center has also been a place where people’s thinking about the relationship between human cities and “wild” places has been challenged and changed.

In 1962, Burress wrote a letter to John Muir, telling the famous naturalist and conservationist that his well-known disdain for urban living was misplaced. Muir believed in connecting with the farthest reaches of the natural environment whenever possible. Burress pointed out that many people didn’t have the privilege to seek nature far beyond cities, and that the wild can be found everywhere, even in an urban environment.

The center thrived throughout the mid-20th century. As it grew, it became a staple in the community. Its collections of specimens on display, education exhibits, rescued animals, and of course, so many birds, wowed visitors and inspired young people to pursue scientific professions and jobs advocating for the environment. School children who grew up in Oakland would take regular field trips to the center, learning from the naturalists and observing local wildlife.

Lake Merritt was North America’s first wildlife refuge. In 1869, Oakland Mayor Samuel Merritt—after whom the lake is named—declared the lagoon to be an official wildlife sanctuary for migrating birds.

Beginning in the early 20th century, the city organized feedings of wild ducks. When the center would hold these feeding spectacles the area would be overwhelmed with ducks clambering to snatch a slice of bread. In addition, the Rotary Nature Center had small coin-operated feeding stations where children and adults came to feed birds. While these feeding activities no longer take place—due to the now understood negative impacts of feeding birds food that is outside of their natural diet—the city did establish several bird islands throughout the lake to provide a home for Oakland’s avian residents. The islands are still there today, used by hundreds of birds to roost.

David Wofford, a lifelong Oakland resident and co-chair of Rotary Nature Center Friends, a nonprofit organization focused on environmental stewardship and education, was always excited to visit the center as a child.

“It was a very fun time. Sometimes it involved my classroom, other times it was just friends and family visiting the Lake,” said Wofford. “It was a bright sunny time. I looked forward to going.”

At its peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the center had four full-time employees and numerous volunteers. It was during this time that the city and Paul Covel hired another employee, Stephanie Benavidez, to help run the center.

Covel retired from the center in 1975, although he kept volunteering for years after. Rex Burress, the center’s next supervising naturalist, retired 20 years later. When Benevidez took over as the center’s lead naturalist in the 1990s, she had been working at the center for some time, and according to Jim Covel, his father was thrilled to have her take on the role.

Budget cuts and hard times

Those who know Benavidez said she was all about community involvement and accessible education as the Rotary Nature Center’s lead naturalist. Benavidez used to drive around in her “nature van” bringing educational materials and interactive exhibits to folks throughout Oakland.

“When my dad retired, boy she jumped into that with both feet and did such an amazing job with picking up that program,” said Jim Covel.

However, starting in the 1990s the Rotary Nature Center’s budget started to shrink. The city had other priorities and less revenue to fund essentials like public safety and fixing roads. Positions were cut. Eventually, Benavidez was the only full-time staff member. Even with volunteers and some part-time staff, most of the responsibilities fell on Benavidez’s shoulders. The work was overwhelming. Over the next couple of decades, the center continued to stagnate. The city didn’t provide significant funding and it seemed to many like the city no longer valued it.

In May 2017, city leaders confirmed that they were investigating how the Rotary Nature Center was being mismanaged, including the alleged mistreatment of rescue animals. Sources with knowledge of the investigation said the city’s refusal to adequately support the center, and personal issues in Benavidez’s life, created a crisis. The animals, which consisted of several reptiles, a tortoise, two guinea pigs, and three birds, were in rough shape. The animals were found living in filth, their cages stacked and shoved into small spaces. The center was shut down. Benavidez took a different position in the city’s parks and recreation department before retiring. And the center stopped accepting rescue animals.

This incident was a devastating blow to the nature center. It was also a wake-up call. As the city discussed how to move forward, Dianne Fristrom, the founding member of Community for Lake Merritt, the Rotary Nature Center’s official fiscal sponsor and Lake Merritt stewardship group since 2016, swooped in with a $100,000 donation to renovate the center in 2018, essentially saving the building from an uncertain future. As renovations began, the center reopened briefly. The pandemic followed shortly after and once again the building was closed.

A light at the end of the tunnel finally seemed to appear when the city hired Oakland resident Sonomia Byrd to run the center a year and a half ago. There had been a couple other directors that had been hired to run the center before her, however, Byrd is now the longest serving director since Benavidez.

“My dad was a blue-collar worker, retired from PG&E, father of five, my mom would work in the nursing industry.” Byrd said. “And with five kids at the time on just one salary, this was the place where we would go.”

Byrd had worked at the center in her early twenties and at the time was in awe of Benavidez’s ability to connect the community with nature. She said watching Benavidez work was like “seeing a magician create magic out of thin air.”

Byrd came in with big plans for bringing the center into the 21st Century. She worked with the city of Oakland to create a budget for the center that would allow her to bring in modern technology, interactivity, new programming, language inclusivity, and more for its array of visitors.

However, in September, yet another shocking incident threw the future of the nature center into question.

The center ablaze and an uncertain future

Wofford rushed to the center when he heard there was a fire. He and other members of the Rotary Nature Center Friends group were panicking, calling each other, and fearing the worst. When he got there, Wofford was relieved the building was still standing.

The fire, which broke out on September 17, burned 15% of the outer wall and a portion of the roof. While the damage to the specimens and educational materials was minimal, the building will require a fresh coat of paint to address smoke damage. The fire’s cause still hasn’t been determined, according to the city.

Whatever the fire’s cause, Katie Noonan, the founder of Rotary Nature Center Friends, and others feel that the building has been put at risk because it’s been closed for so long. Years of disuse and dilapidation have left the center vulnerable. While Noonan understands the intricacies that come with city funding, she, and so many others, want to see the center up and running.

“I don’t know the whole story about what they’re dealing with, so I don’t want to point fingers,” Noonan said. “It was frustrating, and saddening that as the world kind of deteriorates in so many ways that this incredible asset isn’t being used to educate people and bring people together. ”

The fire was just one more blow to the community members that have poured their time and energy into getting the center back on its feet.

Byrd said that although the fire was another setback, it was also a blessing in disguise. She said it gives them the time—and clear incentive—to put the work in to get the center up and running. The processes that need to occur for the center to finally reopen are complicated and require funding that takes time to acquire, said Byrd. She has faced some pushback from community members who don’t agree with the current pace of the repairs, but she wants people to remember that she cares for the center.

The Rotary Nature Center was the first of its kind and has touched the lives of countless Oakland residents. While it has been through its ups and downs—and now as it recovers from the fire—community members are imploring city officials, Oakland residents, and environmentalists to finally provide the resources and attention they believe the center deserves.

Jim Covel believes Oakland has always been a leader in environmental education, helping to bridge gaps between the natural environment and the community. He hopes that the nature center can continue to be a place for those looking to engage with the natural environment and learn from the experts, as people once could when his father started there 70 years ago.

“I’d like to see the nature center as a symbol—as a tangible home—for an idea and a program that really covers the whole city and allows citizens of Oakland to be citizens of a natural world and to remind us that we still have a lot of nature around us in Oakland and to celebrate that.” said Covel. “With all of the other things that they have to fund and support, I hope that the people that have to make those kinds of choices can still remember that there used to be, and still can be, a really robust nature program there, hopefully we can get back to that.”

That’s a mission that Byrd said resonates with her.

“I was born and raised in Oakland. I feel like this is my backyard, as well as everyone’s backyard who visits Oakland,” Byrd said. “How can I deliver to them a nature center in the vein of Paul Covel and Bugs Cain and Stephanie and all these amazing naturalists that came before me?”