Mountain View Cemetery at the top of Piedmont Avenue is known for its breathtaking views and green meadows, and buried beneath its stately tombs and monuments as eternal residents are influential historical figures like Henry J. Kaiser, Anthony Chabot, and Julia Morgan.

But Oakland was already a growing city before the cemetery buried its first person in 1865. Where were Oakland’s earliest residents buried?

Long before the Gold Rush brought settlers west and Oakland was founded, Mexicans, Californios—descendants of California’s early Spanish settlers—and Native people buried their dead in a variety of sacred places. Present-day Emeryville was home to one of the largest shellmounds in the East Bay, where the Ohlones buried their dead for thousands of years. Numerous other shellmounds existed throughout the East Bay but were destroyed by Spanish missionaries who arrived to colonize the land and its inhabitants.

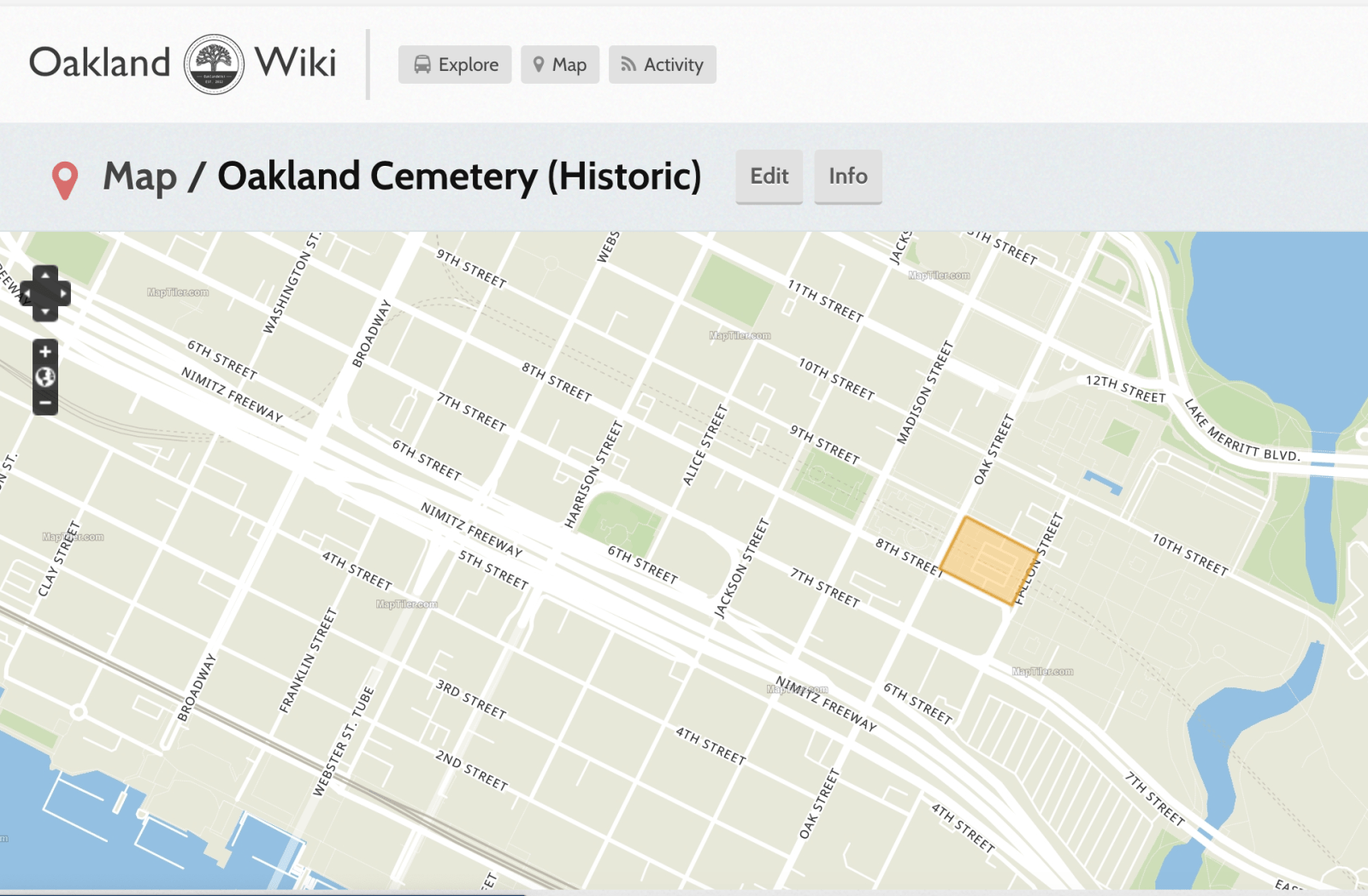

When Oakland was established in 1852, the city had only one graveyard, the Oakland Cemetery, located east of Oak Street between 7th and 11th Streets. At the time, this was the edge of town, and Oakland’s population was only about 100 people. In 1854, a diphtheria epidemic swept across the then-small village of Oakland, killing many children. There are few records of Oakland Cemetery because, according to an Oakland Tribune story from 1952, “the man in charge of the first official cemetery could neither read nor write—and the first 10 or so years of the community’s passing are uncluttered by records.”

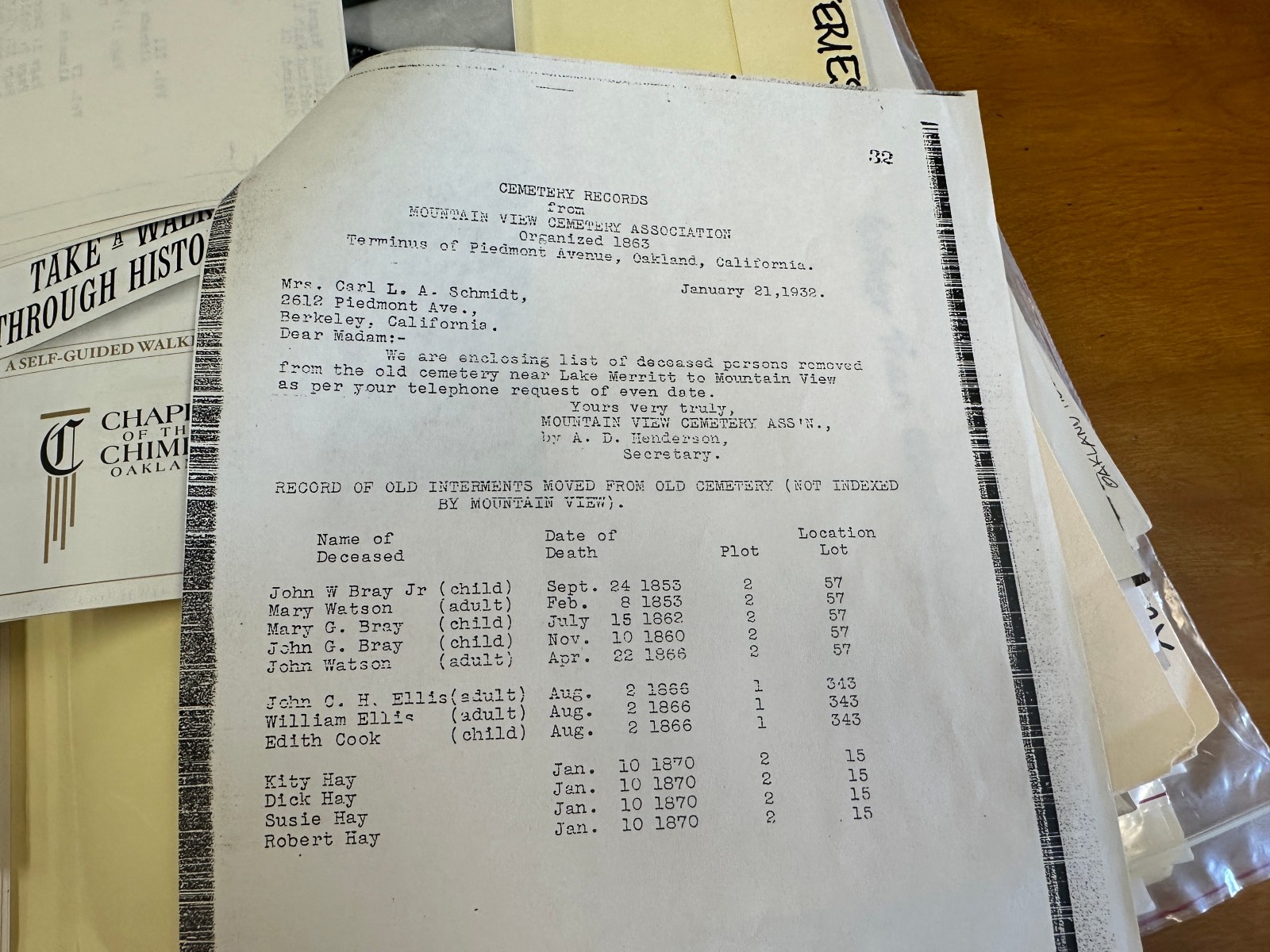

However, at least three family members whose descendants still have ties to Oakland were buried at Oakland Cemetery: John W. Bray, Jr., who died in 1853; John G. Bray, who died in 1860; and Mary G. Bray, who died in 1862, all children. John and Mary were the children of Watson Augustus Bray, one of many businessmen who became wealthy during the Gold Rush, and his wife, Julia Moses. The couple had five other children, including Emma Bray, who was gifted the Cohen Bray house museum in Fruitvale as a wedding gift. The descendants of Emma and Alfred still own the house today.

The remains of the three children, along with nine other bodies, were moved from the old cemetery near Lake Merritt to a second cemetery opened in 1857 and later to Mountain View Cemetery.

Oakland historian and researcher Gene Anderson, author of Legendary Locals of Oakland, has indexed pages on the Oakland Wiki—a contributor-created site all about the city’s history—with records of both cemeteries.

Anderson said that contrary to what some old newspaper articles say and based on maps from when Oakland was first built, the original Oakland Cemetery didn’t stretch past 10th Street. Instead, it only took up an area from Oak to Fallon Street between 8th and 9th streets, where Lake Merritt’s BART parking lot is now located.

As the city grew, so did the need for a larger eternal resting place for its residents. In 1857, the City Council approved creating a new cemetery on a plot of land bordered by Webster and Harrison Streets and 17th and 20th Streets. According to an 1875 story in the Daily Evening Tribune, 40 to 50 residents were buried at the new Webster Cemetery, which was meant to be permanent.

But it wasn’t as eternal as city leaders hoped.

By the summer of 1863, as Oakland’s population rapidly grew, the Webster Cemetery was deemed insufficient, and the remains were dug up again. According to the Daily Evening Tribune, after the remains were moved, curious visitors to the former graveyard encountered “dilapidated enclosures” and “myrtles blooming in profusion.”

The area where the Webster Cemetery was located is now a mix of commercial and residential buildings, including new high-rises and the historic Howden Building. According to Anderson, the cemetery extended into what is now Snow Park.

A monumental burial ground rising in the hills

In the winter of 1863, a group of prominent Oakland leaders formed the Mountain View Cemetery Association. They identified a 200-acre parcel outside the then-city limits and owned by one of the association’s founding trustees, Rev I.H. Brayton. Brayton sold the land to the city for $13,000.

The Mountain View Cemetery opened its doors in 1865. The first burial was that of 43-year-old Jane Waer, who died of “bilious fever.”

Due to limited records of Oakland’s first and second cemeteries, it is unknown if all the bodies from both were removed and relocated to Mountain View. What is known is that the development of the land they once occupied downtown was a hot-button issue at the time.

In 1874, The Oakland Daily News wrote a scathing story denouncing the “revolting and unchristian spectacle” of seeing roads and homes built where both cemeteries once stood. The newspaper mentioned how, at the time, there were “still hundreds of graves there, and there is no legal process by which they can be removed.”

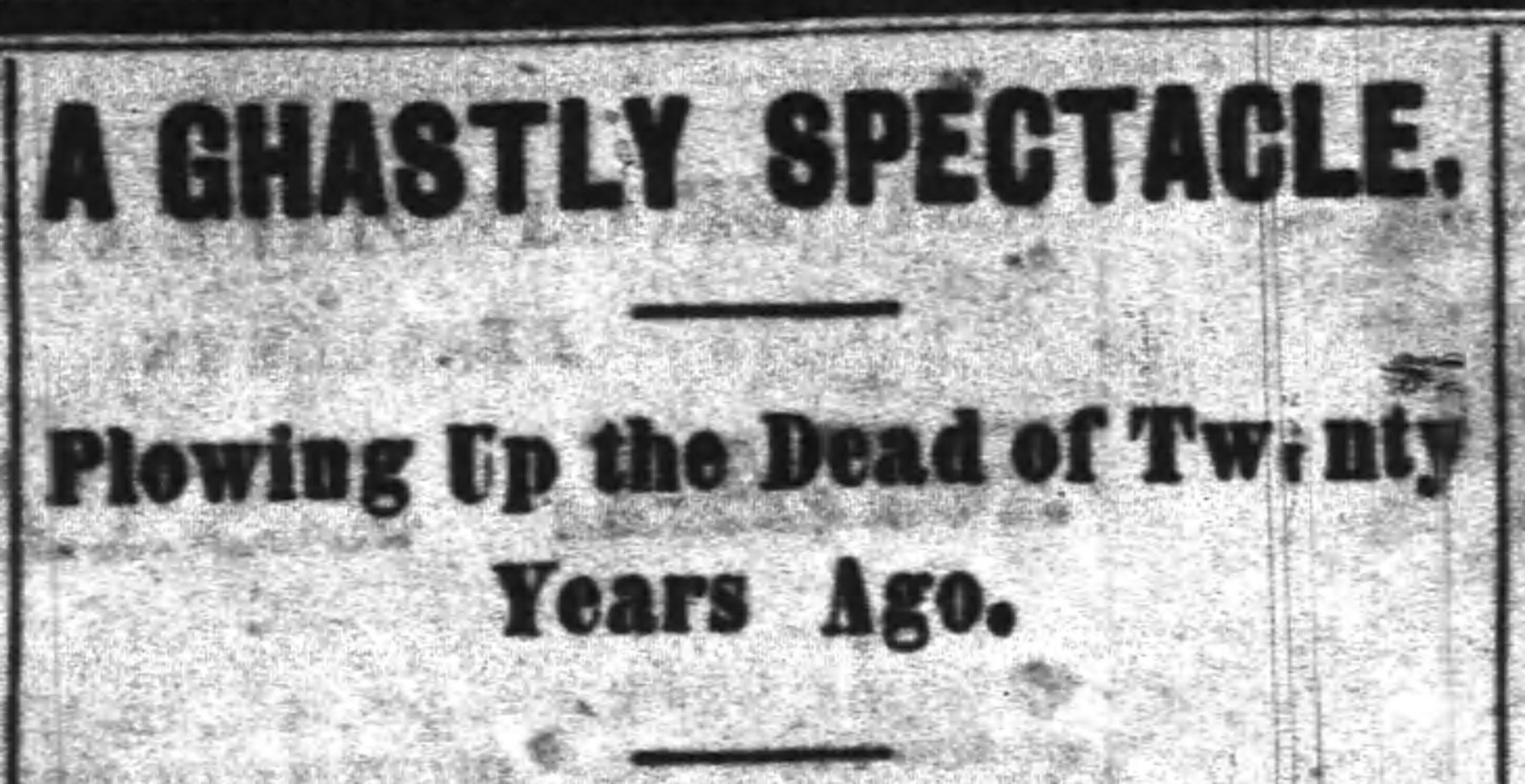

In 1877, another scandal broke out when an excavator plowed into the ground where the Webster Cemetery once was and hit a metallic coffin. Little was done to prevent the casket from being destroyed. Instead, the lid was torn off, exposing a person’s remains to the elements. According to the story, 22 bodies were dug up during the excavation.

A reporter from the Oakland Tribune described the scene.

“The left hand and arm nearly to the elbow protruded from the ground, the hand drooped over gracefully from the wrist. Portions of the coat and vest were visible, as were the outlines of the face, but over these still rested a coating of fine earth.”

The Tribune reporter determined that the body was that of William F. Denman, a civil engineer who died in Oakland in 1860.

With so many years having passed and with so much change, it’s hard to imagine that parts of downtown Oakland were once used to bury hundreds of people. But as you roam the city, remember to stop and think about what may lie below your feet. Consider this from the same Tribune reporter who witnessed the desecration of graves 146 years ago:

“Many bodies still lie buried under the surface of Webster Street, where the tramp, tramp, tramp of the living, and the whirl of the vehicles will probably continue to disturb their bones until time shall be no more.”