Bay Area FM radio news listeners knew him as Scoop Nisker. Buddhism students knew him as Wes Nisker. Readers knew him as a performer and author of Crazy Wisdom, Buddha’s Nature, and other books. I knew him as a close friend and spiritual big brother who encouraged and challenged me to be a better me and smile in the face of life’s absurdities. On Monday, July 31, after nobly struggling for a few years against the ravages of Lewy body dementia, Wes “Scoop” Nisker joined other crazy wisdom masters in that big comedy club in the sky. He was 80 years young.

A native of Norfolk, Nebraska, he moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s after studying at the University of Minnesota and Columbia University in New York. “I went to San Francisco in order to be a beatnik but I was too late, so I was assigned to the hippies,” as he often said. He called Oakland home since 1975.

Almost exactly 20 years ago I profiled him for the New York Times in a piece about “the world’s first Buddhist stand-up comedian,” describing his style and cadence: “He delivers Zen zingers with Borsch Belt timing.”

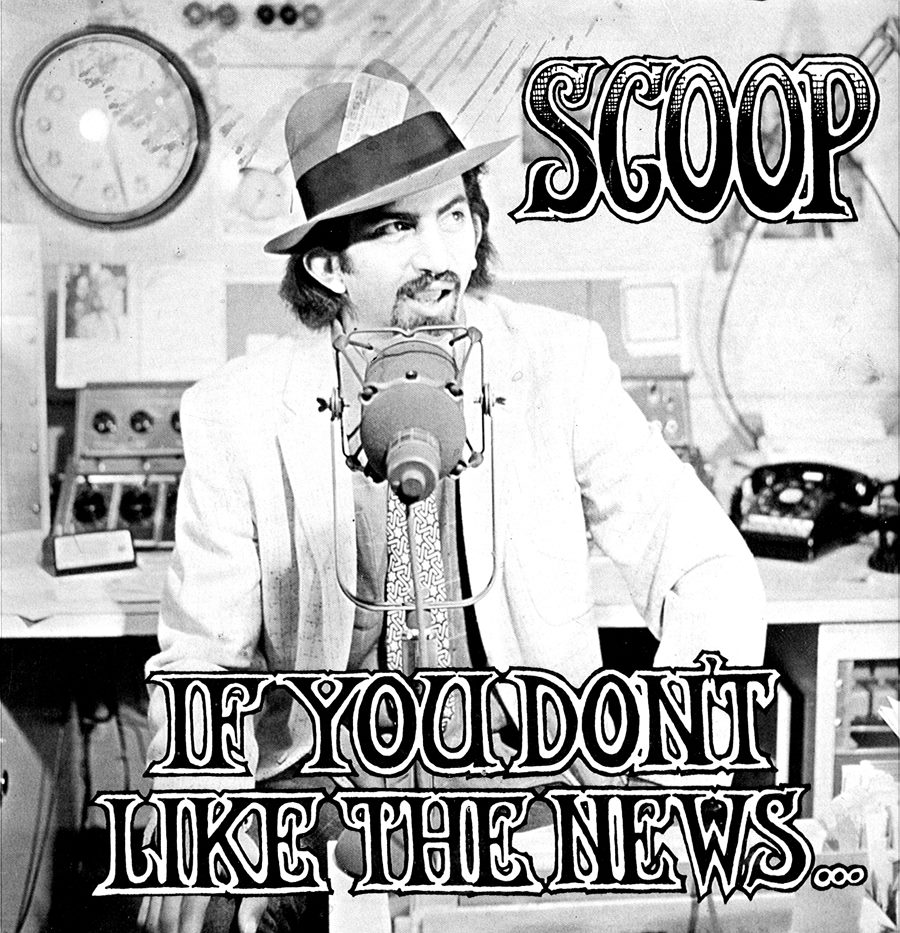

First with KSAN from 1968-72, later with KFOG, and often on KPFA, he was a pioneer at the forefront of a new way of reporting news tinged with opinion. He delivered the news with a rock music background—news you could dance to. Railing against capitalism and big business, war, environmental degradation, hypocrisy, and new age banality while promoting “peace, love and good vibes,” he created audio collages that interwove sound bites with the sounds of our times, like the sound of whirring helicopters that became all too familiar during the height of the Vietnam War drowned out by Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War.”

“He was a perfect example of new free-form radio back in the late ’60s,” Ben Fong-Torres wrote to me. The veteran Oakland journalist, formerly with Rolling Stone, wrote radio columns for the Sunday Chronicle-Examiner’s old Pink Pages that were once must-read fare for media junkies. “It’s hard to talk about his influence on FM radio news because he was like what Bill Graham said about the Dead: they were not only the best at what they did, they were the only ones that did what they did. Scoop was singular. Other radio newscasters, writers, and reporters could admire what he did, but they couldn’t copy him, with his blend of cosmic comedy, anarchic and humanistic politics, and technical dexterity, working music and audio clips into his reports. Good thing he produced an album, several books, and stacks of airchecks so that people beyond the Bay Area can appreciate a broadcaster and performer who was truly one of a kind.”

His news reports were called “The Last News Show,” perhaps in the hope that there would be no bad news to report the next day. His signature closing to each show became a rallying cry to incite activism: “If you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own!” But it was the line before that that indicated his hope for Humankind: “Stay high but keep your priorities straight.”

His other signature was his “man on the street” interviews, most of them conducted on Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue from Dwight Way to Bancroft. It seemed as though everyone knew and loved him. They came up to him—“Yo, Scoop!”—or shouted greetings from across the street. He always said hello back, but later would disclose he often had no idea who his greeters were. While he loved being recognized and adulated, he was a private person, playing his emotions close to the chest. There was something at once familiar and enigmatic about him. As opposed to his rapid-fire verbosity on air, he could say so very much in so very few words off the air.

During his career, he received awards for excellence from Billboard Magazine, the Columbia School of Journalism, and the San Francisco Media Alliance. He was also inducted into the Bay Area Radio Hall of Fame. He performed his stand-up comedy act at meditation retreat centers and on stages throughout the Bay Area and Southern California.

He kept close to his closest friends: Jerry Mander, who worked for Public Media Center and author of “Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television”; Paul Krassner, founder and editor of The Realist; Darryl Henriques, former San Francisco Mime Troupe member, a caustic comedian who played the Swami from Miami opposite Wes; Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield, both at the forefront of the American Buddhism movement.

Kornfield, as much a Buddhism teacher to Wes as a friend who’d been on retreats with him in Asia, wrote on his website last week: “When one of your best friends and spiritual brothers dies, it’s hard to put into words all that it means. Sad and tender, hard to fathom, and also a loving relief for his release from a deteriorating body. Wes spoke with wisdom, humor and wit and had a stunningly unique and creative perspective on the mystery of human incarnation. He was a Bodhisattva who loved to play. He regaled us and awakened us through his books, plays, decades of revolutionary journalism, publication of the Inquiring Mind, and many years of dedicated Dharma teaching.”

Since childhood, he had an inquiring mind. Eventually, with writer and editor friend Barbara Gates, he cofounded Inquiring Mind, the semiannual international journal covering thoughts and trends in the insight, or vipassana, meditation movement based on Buddhist philosophy and practice. Soon he became a teacher at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in West Marin and a member of the Spirit Rock Teachers Council.

After “If You Don’t Like the News, Go Out and Make Some of Your Own,” his focus turned to writing about how to live a Buddhist life in the midst of these un-Buddhist times. His very popular “Crazy Wisdom” gave rise to two more repackaged versions of it. Following those, his literary output stayed with the themes he cared most about, with “You Are Not Your Fault and Other Revelations,” “Buddha’s Nature,” and “The Big Bang, the Buddha, and the Baby Boom: The Spiritual Experiments of My Generation.” The latter two were just reissued in the last six months. In the works was an event at his beloved City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, which event may or may not still happen. Stay tuned.

Lewy body dementia sucks. Little is known about it; there is no known cure. Dementia with Lewy bodies is estimated to affect 1.4 million people in the United States. It accounts for about 5 percent of all dementia cases in older individuals and is the second most common dementia after Alzheimer’s disease. Among those victims was actor and comic Robin Williams, whose diagnosis was revealed by his widow only after he took his life. Lewy body dementia results from the buildup of proteins into masses known as Lewy bodies; the protein also is associated with Parkinson’s disease. In addition, the disease is associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

I first noticed something off with Wes five years ago. At a dinner celebrating my birthday, a group of us were laughing and riffing over dinner at Yoshi’s in Oakland. He started talking about an episode from his favorite TV sitcom, which he watched in reruns every night after dinner and the news. He knew the show so well he could lip-synch the dialogue. He’d nonetheless laugh at each schtick as though he’d seen it for the first time. But that night at Yoshi’s he could not recall the name of the show: “Seinfeld.” I often joked that he loved the show because it famously was a “show about nothing.”

Over the next two or three years I observed a few times with him which reminded me of my mother who suffered from dementia and then Alzheimer’s in the last year of her life. One day Wes drove us somewhere and after he parked, I saw him lock his car, put the keys in his pocket, then take out the keys, unlock and relock the door, repeating this several times until I called him to come along.

His hands began to shake so badly that he needed help opening the plastic wrapper of Babybel cheese. He began to walk gingerly, struggling with his balance to the point where his family decided to move him to The Lake Merritt, which was then housing for seniors. Our walks to the Lake Chalet across the street and a few hundred yards along the lake became slower; he needed to sit and rest on a bench en route. His frustration was palpable. When the Lake Merritt owners changed it to a regular apartment complex, his family moved him to The Point at Rockridge.

In need of much more day-to-day help, he moved once again to what would be his final stop: Elder Ashram in the Fruitvale section of Oakland. With each move, I saw a decline in his cognition. The man with the silver tongue stumbled over words, losing track of what he was saying halfway through a sentence. Yet, he’d still come out with one of his classic Zen zingers, a skewed view of whatever what happening around him and to him. “Surreal” was a word he often used in the last year.

He loved jazz. He loved haiku. He loved puns. He loved hating the mostly bad news. He loved Oakland and Berkeley. But most of all, he loved his daughter Rose Nisker, who he has sweetly shared with his dear friend and former wife, Mudita Nisker, also of Oakland. Rose—full disclosure: she and my daughter Ariana are closest of friends; she is my granddaughter’s godmother and takes the role quite seriously—is herself a star. She started dancing with Berkeley’s Balinese Gamelan Sekar Jaya at the age of 6, performed with them in Bali at 8, years later became its director, and now is a mindfulness producer at the meditation app Calm.

Rose organized his care team, orchestrated Zoom calls for him, encouraged him to keep on repackaging his books and other writing, and nagged him to eat more. She always looked up to her father with pride and awe. She basked in his shadow at events, her big smile beaming. In the last week, she’s been tracking down more Scoop samples on his YouTube page.

I got this assignment from The Oaklandside to profile Scoop two weeks before he passed away. A few days before his last breath, we had mapped out an hour here and there for a series of interviews so as not to wear him out.

That never happened. So I’m left without answers to the questions I’d wanted to ask him. “Have your meditation practice, Buddhism studies, and readings helped you cope with your current reality? How so? Can you look at this all as one big cosmic joke that only the Trickster in you would get? Are you in much pain? What’s it like inside your mind now? Do you have regrets as you look over your life? What do you want to be remembered for most?”

Knowing him as well as I did, I suspect he would answer questions in his last days with some combination of Alfred E. Neuman’s “What, me worry?” and the Indian mystic Meyer Baba’s “Don’t worry, be happy.”