Every Wednesday, Vicky Ju shows up at The Cook and Her Farmer oyster bar and wine cafe at Swan’s Market in Old Oakland to pick up a 5-gallon bucket of discarded oyster shells. The volunteer then drives to the REAP Climate Center in Alameda, a science center focused on regenerative processes and biodiversity. There, she spreads the shells out in a chicken coop for the birds to eat whatever remaining abductor muscles are attached to the shells.

Learn more, get involved

Point Pinole oyster restoration

Presidio oyster restoration

EcoCenter at Heron’s Head Park oyster restoration

“Save Our Shucks” programs at REAP Climate Center and Bay Natives Nursery

Once picked clean, the shells are moved once again to the roof of a shipping container on the REAP campus, where they will sit in the sun for two years—yes, two years—to bake off any potential living organisms. Finally, volunteers use the shells to make oyster cages and reef balls to create new habitats for oysters in the San Francisco Bay.

It’s a long process, but one that Casey Harper, Deputy Director of the Wild Oyster Project, believes is worthwhile.

“The shells we collect from local restaurants are a great substrate for larvae to attach to a hard surface, form into spat [baby oysters], and build new reefs,” she said.

Only an estimated 1% of the native Olympia oyster [Ostrea lurida] still exist in the San Francisco Bay, and Harper and her team are working to bring them back.

They’re focusing on oysters, because, Harper said, “they act as a natural buffer against flooding and sea level rise. And they’re great filters, with adult oysters filtering gallons of water each day and cleaning pollutants out of the Bay.”

To be clear: the Wild Oyster Project is not reestablishing oyster beds in the Bay for human consumption. Rather, it’s to provide a place for native oysters to thrive and a food source for wild animals.

Long history of oysters in Oakland and the bay

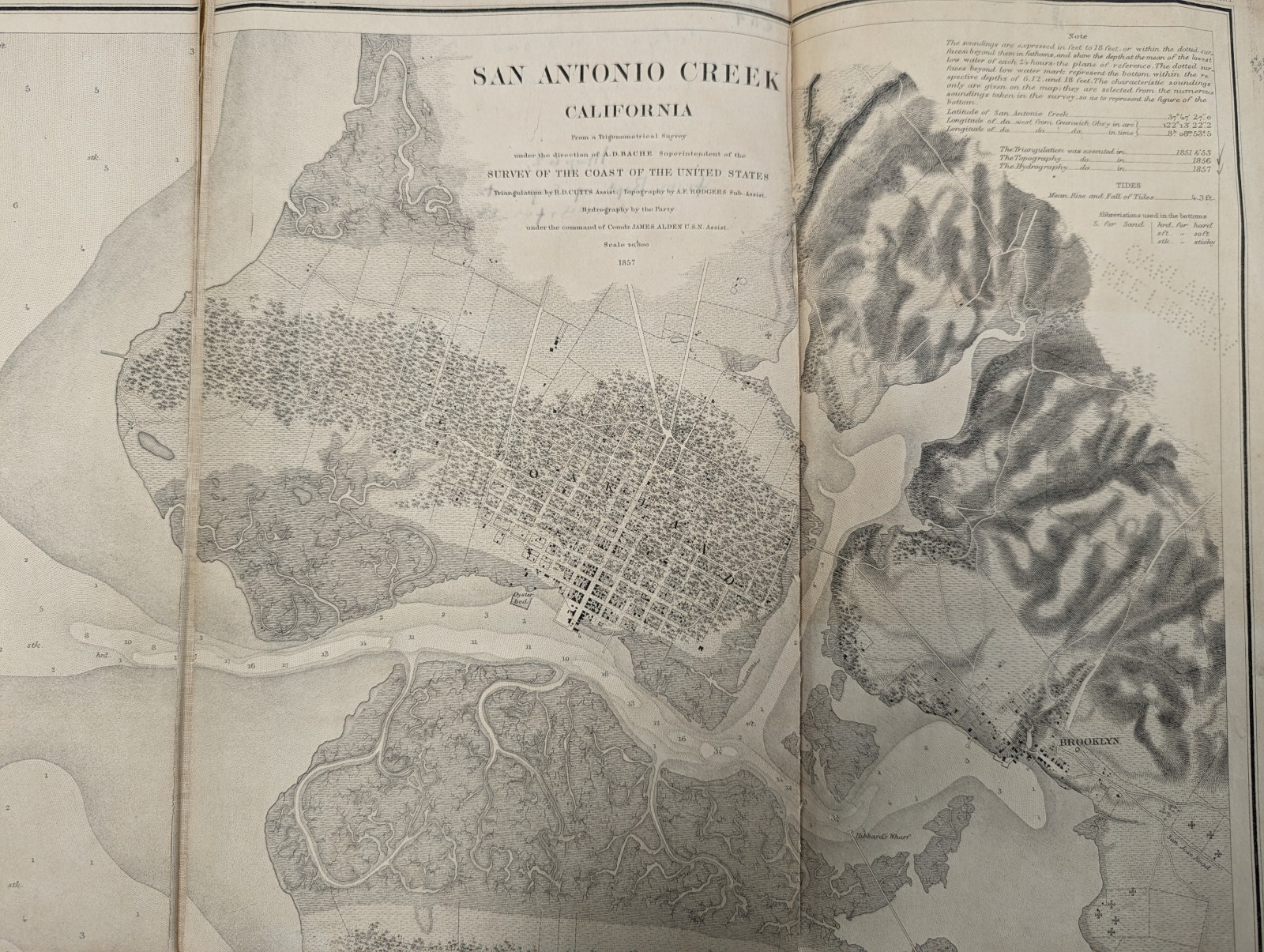

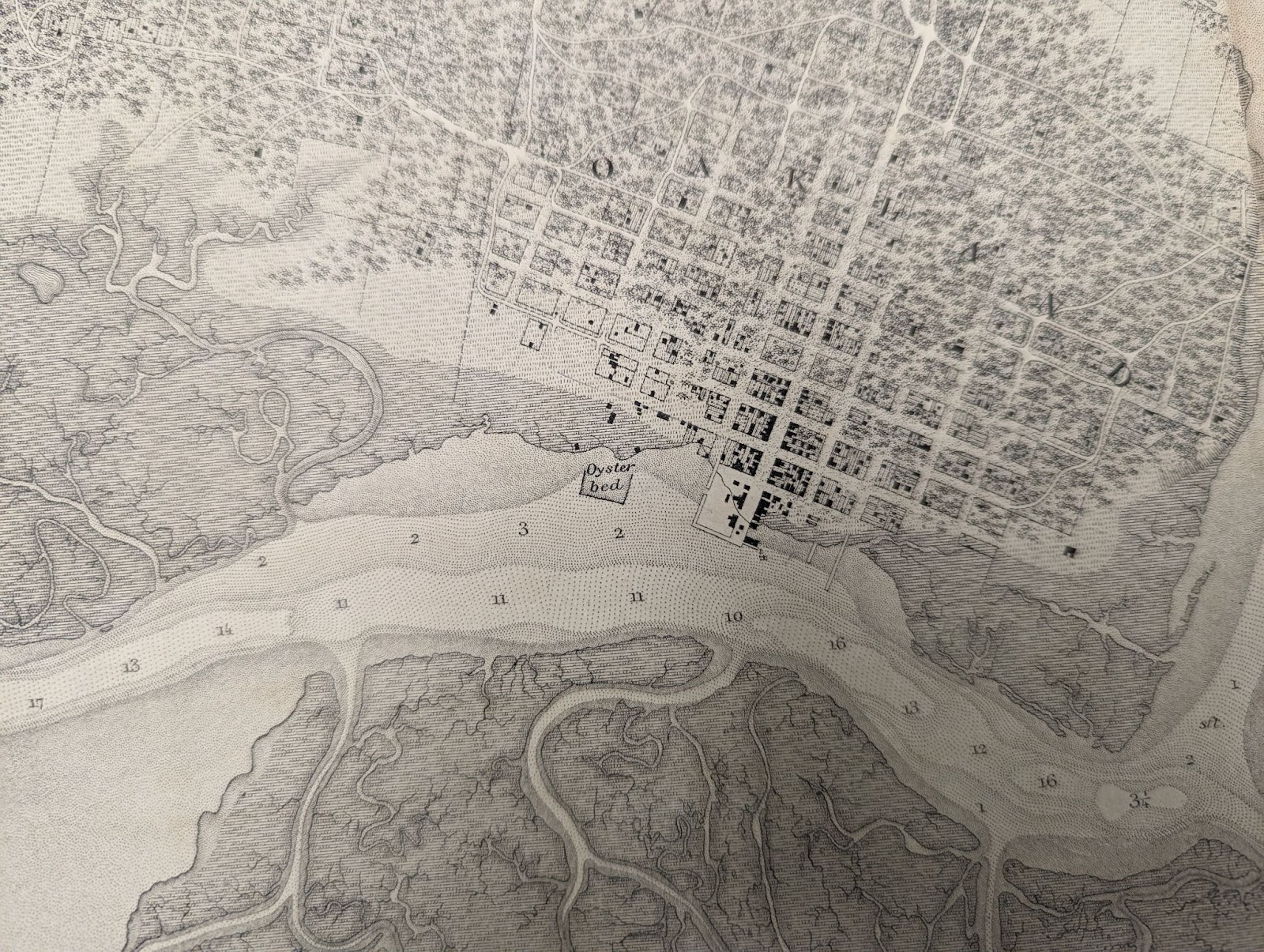

Shellfish, including oysters, were an integral part of the economy and diet of Native Americans in the bay. We know this because of the record of large shellmounds that the first inhabitants of the Bay Area created, including in East Bay locations such as 1901 Livingston St. in Oakland, 1900 Fourth St. in Berkeley, Mound Street in Alameda and Shellmound Street in Emeryville. These mounds included many oyster shells, among other shellfish, which were then abundant locally.

The native oysters were small, flat Olympia oysters which had a coppery taste and took longer to grow than East Coast varieties. Starting in the 1850s, this variety was supplanted by larger oysters of the same species, imported from Washington State by boat to create the first commercial oysters beds in the San Francisco Bay, including in the Oakland Estuary.

In 1869, when the transcontinental railroad opened, some of the early train cars brought fresh oysters to the bay from as far away as Baltimore. Soon, oyster larvae and spat were being imported from New York Harbor by train and planted in oyster beds in the bay. These larger, and faster-growing, oysters (Crassostrea virginica) were more palatable to the European immigrants moving to the bay, and, by the late 1800s, it was this species that was largely being planted in local oyster farms.

Jack London the poacher turned catcher

Dennis Evanosky leads walking tours of Alameda. On a recent stroll, the Alameda Post historian talked about how oysters once dominated the economy of Bay Farm Island, which is next to the island of Alameda.

“Jack London called it ‘Asparagus Island’ in John Barleycorn because of the asparagus farming here,” he said. “But what really took off was oyster farming. It was so successful that oyster pirates emerged who stole oysters from beds at night and sold them on the Oakland wharf … and one of these oyster pirates was Jack London.”

“Oyster farming…was so successful that oyster pirates emerged who stole oysters from beds at night and sold them on the Oakland wharf.”—Dennis Evanosky

Ironically, London later went on to become a deputy in the fish patrol, cracking down on illegal fishing and oyster pirating, which he wrote about in A Raid on the Oyster Pirates.

“There were shared beds in the middle of the bay, and the oyster industry that started in the Oakland-Alameda estuary and Bay Farm Island was later moved south, to the shores of San Leandro and San Lorenzo,” Evanosky said.

What happened to the local oysters?

There were several factors that led to the decline of native and farmed oysters in the San Francisco Bay. One of the main culprits was the sediment that washed into the bay from hydraulic mining during the Gold Rush.

“Oyster larvae need something hard to attach to: a rocky surface or ideally another oyster shell,” said Harper from the Wild Oyster Project. “Once much of the bay’s bottom went from rocky to silt, it was hard for oysters to find areas to attach to.” Harper adds that events such as the Great Flood of 1862, which turned much of the water in the bay into freshwater, proved catastrophic to the oyster population.

“Oysters thrive in estuaries, where there’s a mix of both freshwater and saltwater,” she said. “If the water gets too fresh or too salty or polluted for too long, the oysters will die off.”

And die off they did, compounded by untreated wastewater being dumped directly into the bay, and pollution caused by burgeoning industrial plants in the late 1800s.

A contributor to the shrinking number of oysters in the waters near Oakland was the Standard Oil refinery, which used to be located at the old Alameda Point. Evanovsky points out that, between 1879 and 1903, ships from Southern California carrying crude oil would dock at the then western edge of Alameda, where it was refined into kerosene. The refinery was dismantled in 1903 after a new one was built in Richmond, which was later expanded to become the Chevron Richmond Refinery. The original site, next to the Alameda Naval Air Station, has remained unoccupied since 1903 and is still pending cleanup.

Infill of the bay’s shoreline is another factor in the decline of oysters. That includes when infill from BART tunnel excavations in the late 1960s was used to create the present-day Port of Oakland.

Engaging a younger generation

Steven Day, the co-founder and co-owner, with Romney Steele, of The Cook and Her Farmer, is contributing to the multiple initiatives underway to help restore oysters in the bay. Day was an evidence recovery diver for the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office, and, along with Steele, has experience farming oysters in Tomales Bay. Day currently teaches at Oakland Unified School District, where he tries to get kids more connected and informed about their environment.

“I see my wider goal as a teacher to get my students to dig into Oakland soil, find a place, and have a responsibility to become aware of it,” he said. “[I empower my students to have] an awareness of the world, and become more self-aware; to add sentience to being a human being. Yes, I’m living, but what does that mean to how I’m connected to the environment around me?”

When the Wild Oyster Project reached out to the restaurant to ask about donating its used oyster shells for its “Save Your Shucks” program, Day said it was a no-brainer to join. He and Steele see the donations as part of a larger effort to not only bring back native oysters to the bay, but also to use the opportunity to teach kids in Oakland about how to get more engaged in their environment and surroundings.

“When kids are in the fourth through sixth grades, you throw everything at them because they’re in the age of discovery,” said Day. ”You would be amazed at how many of my students have never touched the ocean. We need to get those young folks more in touch with this incredible aquatic life at our doorstep. We have a responsibility to be stewards of the earth, and I’ll leave this earth a happy person knowing that I’ve done my part to help make this happen.”