Did a veteran Oakland police officer send two men to prison for life by bribing an informant—and then commit perjury to cover his tracks?

Or was this a case of zealous but sloppy police work, with an officer scrambling to secure righteous convictions after a callous killing—and to keep his star witness safe from violent threats?

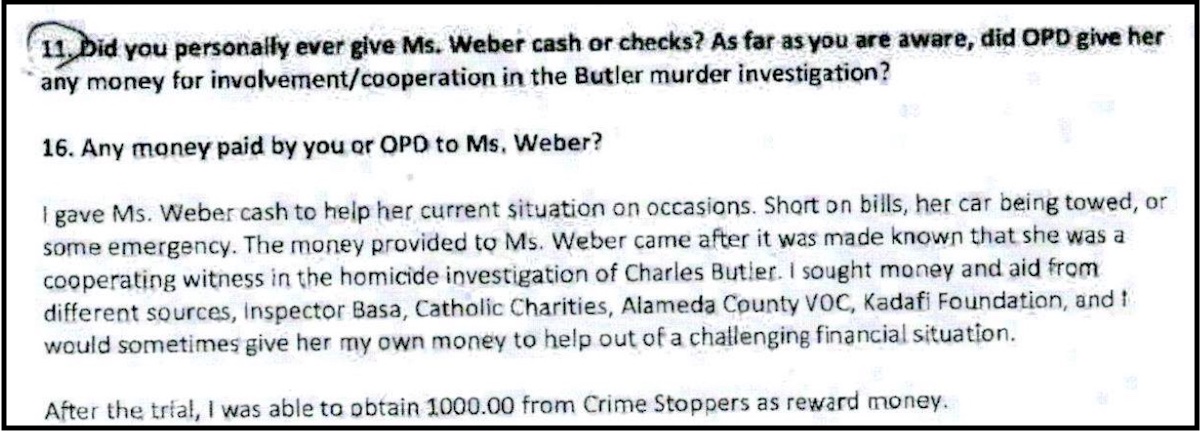

OPD Officer Phong Tran faces criminal charges of felony perjury, bribery, and witness intimidation for allegedly making secret cash payments to Aisha Weber, whose testimony sent Giovonte Douglas and Cartier Hunter to prison for the December 2011 killing of Charles Butler in North Oakland.

When attorneys for Douglas and Hunter appealed their convictions two years ago, they revealed that Tran had made previously undisclosed payments to Weber before, during, and after the 2016 murder trials. They included a sworn declaration from Weber in which she recanted her testimony, saying she lied to OPD investigators and the jury about witnessing Butler’s killing to secure financial assistance and housing. And they pointed out that during Douglas and Hunter’s trials, Tran testified under oath that he’d never met Weber before she came forward as a witness in the case—even though Tran later acknowledged they had first met two years before the murder.

This new information convinced a superior court judge that Tran’s actions had tainted the cases against Douglas and Hunter. Both men were freed last year. Earlier this month, Douglas and Hunter filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Tran and the city of Oakland, seeking monetary damages for wrongful conviction and the years they spent behind bars. And District Attorney Pamela Price decided to charge Tran last month following media reports about the overturning of Douglas and Hunter’s convictions last year.

However, the criminal case against Tran isn’t the first official investigation of his actions in the Butler homicide case—and recent court filings indicate that Tran may have compromised additional murder convictions in his work at OPD and as part of a cold case task force with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

This metastasizing scandal comes as District Attorney Price faces strident criticism in some corners for a perceived leniency towards prosecuting street crime. Some assistant district attorneys—including Amilcar “Butch” Ford, the assistant district attorney who handled Douglas and Hunter’s original trial in 2016—have left the DA’s office, issuing broadsides against Price on their way out the door.

But the criminal charges against Tran deliver on Price’s campaign promise to prosecute Alameda County law enforcement officials accused of criminal misconduct. In January, Price established a new public accountability unit in her office to investigate crimes by public officials, including police, and she has reopened eight cases of in-custody deaths, including several fatal shootings by Oakland police officers.

“Tran’s actions are beyond the pale,” Alameda County Public Defender Brendon Woods said in an interview. Attorneys with the public defender’s office have filed briefs in several cases alleging similar misconduct by Tran. “When you’re orchestrating lies and getting people to testify falsely, you’re committing a greater harm by attacking the underpinnings of our legal system.”

Tran’s attorney, Andrew Ganz of the Rains Lucia Stern law firm, declined to comment for this article. But in brief statements to the media, Ganz vowed to fight the charges, which he describes as “baseless.”

A jury will probably decide whether any of Tran’s actions rose to the level of crimes. Tran has pleaded not guilty and has a preliminary hearing later this week.

“The DA treats murderers like heroes, looking for every possible excuse to keep them out of jail,” Ganz told reporters in a previous statement about the case, referring to district attorney Price. “Yet, real heroes such as Oakland Homicide Detective Tran—who has dedicated and risked his life to try to keep the city safe—are treated like criminals.”

Red flags begin to emerge

The Oakland Police Department knew something was wrong even before Giovonte Douglas and Cartier Hunter’s convictions were overturned. In August 2022, weeks before Superior Court Judge Morris Jacobsen would issue his ruling voiding the two men’s murder convictions, Captain David Elzy, who led OPD’s Criminal Investigations Division, received a call from Deputy District Attorney Timothy Wagstaff.

Wagstaff told Elzy the basics. There’d been a homicide in December 2011. An Oakland resident named Charles Butler was shot in North Oakland after getting into an argument with another driver. OPD investigator Tran was assigned to the case, but there wasn’t enough evidence to file charges against the two men Tran suspected.

The case languished for two years, but then an eyewitness emerged seemingly out of the blue.

Aisha Weber called OPD’s homicide division in early September 2013 and was patched through to Tran. A longtime North Oakland resident, Weber was known to OPD for dealing drugs in the neighborhood and was familiar with the players in the street life. Weber told Tran she’d seen the killing up close. She agreed to an in-person interview with Tran and his partner at OPD headquarters.

Weber told them that on the day of the homicide, she’d seen two men she knew as “Gio” and “Corn” following Butler’s car. She would recount this same story three years later, during their 2016 trials, breaking down in tears while testifying about seeing a green Lexus pull up to Butler’s car while stopped at the intersection. She said Hunter got out of the Lexus and fired “six to nine shots” from a handgun, one of which struck Butler in the head. Butler’s vehicle jolted forward and crashed into parked cars. Weber recognized Douglas, the driver, and Hunter, the shooter, from around the neighborhood, she testified.

Weber’s recollection ended up being the key to the case. She was the only one who could place both men at the scene of the murder.

However, in March of 2022, after the two men had been sent to prison, and while they were appealing their cases, disturbing information emerged. Between 2011 and 2016, Tran used Weber as a source of information, allegedly slipping her up to $2,000 in cash out of his own pocket in exchange for tips about what was happening in the neighborhood, seeing her occasionally on the streets of North and West Oakland. These payments had never been reported to Douglas and Hunter’s attorneys or Tran’s supervisors at OPD.

Moreover, Tran may have lied on the witness stand when he testified at the two men’s trials in the summer of 2016.

During cross-examination, Douglas’ attorney asked Tran if the first time he’d met Weber was when she walked into OPD headquarters in 2013 to give her statement.

“Is this the first time you had any contact with Ms. Weber, in September 2013, to your knowledge?”

“When she came down to my department?” asked Tran.

“Yes,” replied the defense attorney, to which Tran answered, “yes.”

However, Tran had known Weber and used her as a source of information since early 2011, when Tran responded to an unrelated shooting in which Weber had been injured.

Based on this information from Wagstaff, OPD opened an internal affairs investigation to determine if Tran compromised a criminal case by giving cash to Weber and if he lied by testifying that he’d met her for the first time in 2013.

Allegedly paying an informant “to help keep her safe”—but not documenting it

Sergeant Mega Lee was assigned to the case. To hear Tran’s side of the story, Sgt. Lee sat down with him and his attorney, Ganz, last September.

In defense of his actions, Tran said everything he did was to keep Weber safe. And that none of what he did was, to his knowledge, against OPD rules.

An Oakland native who grew up on 20th Avenue and enlisted in the police department in 2006 after serving in the Marine Corps, Tran spent five years working patrol as a problem-solving officer and gang cop before transferring to the Criminal Investigations Division in 2011. He became one of OPD’s most experienced homicide investigators and worked long hours trying to clear cases. When asked by internal affairs, Tran estimated that over roughly a decade, he’d worked on over 700 homicide cases and was the lead investigator for around 50 of these.

In 2021, his total compensation was $427,949.23, $148,495.37 of which was overtime pay.

The Butler homicide, however, was one of Tran’s first murder cases, and he told Lee he was still “getting his feet wet” as an investigator at the time.

Tran told Lee that threats against Weber’s life were made after she came forward in 2013. According to Tran, his investigative files for the case, including Weber’s statement, had been “leaked” before the trial and shared among known gang members in Santa Rita Jail.

According to Lee’s investigation, Tran got a call from a sheriff’s deputy at the jail in mid-2014 telling him that “Weber was known as a ‘snitch,’” and “there was word out someone wanted to kill Weber.”

The next year, the Alameda DA’s office notified Tran about wiretapped calls from Santa Rita Jail which indicated Hunter and Douglas may have been trying to have others dissuade Weber from testifying against them. One intercepted conversation between Charles Johnson and Jonathan Appling, two alleged North Oakland associates of Douglas and Hunter, alarmed Tran. At the time of the call, Johnson was an inmate at Santa Rita along with Douglas and Hunter.

On the call, Johnson could be heard telling Appling to “check” someone named Aisha because she was “getting on the [witness] stand.” Moreno wrote in his report that “Johnson was most likely talking about a witness, and after listening to this, she may be in danger.”

A month after intercepting the phone call, Tran and his partner at the time, Sergeant Caesar Basa, searched Douglas and Hunter’s jail cells. The OPD investigators noted that they found unredacted files of the Butler murder case, complete with witness information.

Another witness in the Butler case, identified in published appellate court records as “D.C.,” also feared retaliation for turning state’s evidence because two of Douglas’ cousins lived on his block, and he feared they would potentially harm him if news of his cooperation became public.

When he spoke with Lee for OPD’s internal affairs investigation last year, Tran said the cash he gave to Weber was “to help keep her safe.” He told Lee he gave Weber anywhere between $1,500 and $2,000, about $500 of it before Douglas and Hunter’s trials. Tran handed Weber this cash outside OPD headquarters and over coffee at a nearby Starbucks. He called the meetings and payments a “welfare thing” as opposed to a part of the case against Douglas and Hunter, and he didn’t document them.

These payments were completely separate from the witness assistance program payments Weber would eventually collect through the DA’s office and a $1,000 OPD Crime Stoppers program payment after the trials concluded.

“In retrospect, Tran felt he should have known better and documented it, and he was being perhaps just lazy at the time,” Lee wrote in her internal affairs report about the undisclosed payments.

According to Tran’s statement to internal affairs, the only other person who knew about the cash handovers to Weber was his partner, Basa, who later became an inspector in the DA’s office and continued working the Butler case. But there’s no sign in any records OPD gathered for its internal affairs review that Basa documented these payments, and he died in 2021—before he could be interviewed about the case.

Lee had to decide whether Tran had compromised the Butler murder case by paying Weber. OPD’s rules state that no officer should improperly influence the legal process or engage in any activity intending to interfere with a criminal investigation or prosecution.

Lee concluded that the payments were above board because Weber’s story about the shooting hadn’t changed from when she gave her first statement in 2013 to the trials in 2016. In other words, Lee’s thinking went; the cash Tran gave Weber didn’t appear to have changed Weber’s claim of having witnessed the murder. Lee also concluded that it has been “an acceptable practice” for Oakland police investigators to make undocumented cash payments to witnesses of crimes.

LaDoris Cordell, a retired Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge and the former head of San Jose’s Independent Police Auditor, told The Oaklandside that police and prosecutors universally understand that paying witnesses and not recording these payments and informing defendant’s attorneys is highly inappropriate. Such conduct, Judge Cordell said, can taint a case to the point that any convictions would have to be thrown out.

OPD’s Departmental General Orders require officers to document their relationships and payments to confidential informants. The policy states that “all informants are assets of the Department, not of the managing officer,” and personal or undocumented financial relationships are forbidden between officers and informants. All financial transactions leading to criminal convictions must be formally documented.

The Oakland Police Department did not answer questions from The Oaklandside about its policies regarding the treatment of informants.

But in her report, Lee of internal affairs flagged the practice of OPD investigators paying tipsters “without proper documentation” as a problem that needed to be addressed. While noting that OPD allows undocumented payments in limited circumstances, she advised that the department “provide training to the [Criminal Investigation] Division on proper payments to witnesses/victims during an investigation to avoid giving the impression that payments are made to influence [witnesses].”

Lee’s finding that Oakland cops can pay informants off-book appears to directly contradict Department General Order O-04, which governs such practices. The guidelines say that all contacts with “temporary” or “citizen” informants—lesser categories than a “managed confidential informant” —are to be documented, as are any payments of assistance or rewards for helping solve a crime.

“That’s prohibited behavior; it’s sneaky, underhanded, and stinks of a quid pro quo,

said Cordell, who investigated similar allegations against a San Jose officer while working as that city’s Independent Police Auditor. “It appalls me that Internal Affairs comes back and says, ‘It’s OK.’”

OPD concludes Tran didn’t lie on the witness stand

In addition to the matter of Tran’s payments to Weber, OPD’s internal affairs also had to conclude whether Tran committed perjury. At Douglas’s 2016 trial, Tran said, under oath, the first time he’d had contact with Weber was in 2013—when she showed up to OPD to give her eyewitness account of the killing.

Tran and Weber had, in fact, first met in February 2011 after she was shot in the arm during a barbeque on 32nd Street in West Oakland. According to statements later made in court and to internal affairs, Tran helped another officer interview Weber that day but noted that she wasn’t cooperative. At the end of the interview, Tran and Weber struck up a casual conversation, and he gave her his phone number, but Tran claims they never spoke over the phone or texted after that. Instead, he told internal affairs he would “only see her [Weber] occasionally when she was out in the neighborhood” while he was working homicide cases.

Homeless and raising two children at the time, Weber told Tran she sold marijuana in West Oakland but wasn’t involved in gangs or violent crime. In written responses to questions from the district attorney last year, Tran described Weber as someone who wasn’t interested in becoming a confidential informant. Still, he wrote that she “was interested in passing on information about dangerous people.” Tran told internal affairs and the district attorney he viewed Weber as a “citizen informant” rather than a confidential informant.

The difference, as Tran explained to internal affairs, is that “a confidential informant is providing information for some sort of benefit, whether it is for payment, or to work off prior criminal activity,” whereas “a citizen informant … is providing information for the betterment of their community.” Tran did not explain why he did not document payments to Weber as a “citizen informant,” which is required by OPD’s informant handling guidelines.

However, Weber did end up providing information in the Butler case with the expectation of financial benefit. As she stated in a declaration to the superior court last year, when Douglas petitioned to have his murder conviction overturned, Weber decided to cooperate with the police in 2013 to secure housing for her family. On top of the money Tran paid her out of his own pocket, Tran also helped line up tens of thousands of dollars in state-funded victim assistance payments through the DA’s office that paid the rent on an apartment, and a $1,000 Crime Stoppers reward for her in 2017. These assistance payments from the DA and OPD were documented, and Douglas and Hunter’s attorneys were made aware of them before the trial.

But while Tran characterized Weber as a petty marijuana dealer, she had been arrested and prosecuted for more serious offenses in the Bay Area and Southern California. Her extensive criminal history through 2011, included in records obtained by The Oaklandside, dates back to 1990 and includes convictions for dealing cocaine, child abuse, felony grand theft, and several probation revocations, one of which involved possession of a firearm and ammunition.

In the grand theft case, which dates from 2008, Weber forged timesheets claiming she provided in-home care services to a woman who had died nine months earlier. Weber pleaded no contest and served five days in jail and five years probation. Her probation was revoked in 2009 following a misdemeanor charge for cruelty to a child, which resulted in court-mandated classes.

In March 2011, less than a month after Weber first met Tran, a warrant was issued for her arrest in Alameda County for wire fraud to obtain government assistance and perjury. The charge could have landed her behind bars for at least a year in addition to violating her probation.

Nothing came of either allegation. Weber’s rap sheet indicates that the welfare fraud and perjury case was “compromised” and dropped by the district attorney in May 2011. The Oaklandside is unaware of any information suggesting that Weber’s involvement with Tran had a bearing on this decision.

Whatever Weber’s motivations may have been, by 2011, she had decided to become an informant for Tran and later a witness in the Butler murder case. But when asked by the defense attorney at the 2016 murder trial if September 2013 was the first time he’d had “any contact” with Weber, Tran answered “yes.”

Tran told internal affairs he gave this answer because all the questions from the prosecution and defense up to that point were focused solely on the Butler case. As Lee of internal affairs put it in her report:

“Tran, due to the past two hours of testimony, interpreted the question to be asking whether September 2013 was the first time Weber came in and met for the Butler case. Tran’s mind was not about any other cases at the time. In the context of the testimony, Tran was only thinking about the first-time meeting with Weber regarding the case.”

Lee wrote in her report that it was “reasonable that Tran did not make mention of his prior contact with Weber on the stand based on the semantics of the line of questioning.”

In her final report, Lee determined both allegations of perjury and compromising a criminal case were “unfounded,” an administrative categorization that essentially means the claimed misconduct did not happen and would not be used against Tran for future performance evaluations.

While evaluating Tran’s conduct in the Butler homicide, Sergeant Lee also reviewed his history of complaints dating back to 2006. In 61 prior cases, Tran was cleared in the overwhelming majority. However, Tran had been disciplined multiple times over the years. In 2008 he failed to turn in a person’s belongings after they were arrested, and he failed to document all contacts with civilians in 2010, violating departmental regulations and his supervisor’s orders. In 2015, internal affairs found he had gotten into an avoidable car crash while on duty. According to two OPD veterans who spoke on condition of anonymity to freely discuss internal disciplinary matters, 61 complaints is an unusually high number.

Most recently, Tran and six other officers were investigated for unprofessional conduct and making derogatory statements. The remarks were recorded on body-worn cameras during the apprehension of a manslaughter suspect that also resulted in a non-lethal police shooting in 2021. Officers’ cameras that had taken footage of the arrest and shooting were taken downtown to OPD headquarters. However, one of the devices, unbeknownst to Tran and other officers, was still recording in the homicide unit’s office. When the audio was later reviewed, internal affairs investigators heard Tran referring to a civilian who had been at the scene of the police shooting as a “lesbian-looking bitch.”

When asked whether his comments were appropriate by an internal affairs investigator, Tran said “he believed he was at the time having an adult private conversation,” and “there was nothing about the conversation he found to be harassing or discriminating to anybody.”

He later conceded that the phrase “lesbian-looking bitch” was an “unfortunate stringing together of words.” Internal Affairs sustained Tran for violating the city’s anti-discrimination and non-harassment policy.

Citing “eerily similar” patterns, public defenders call for a thorough review of Tran’s cases

Following OPD’s decision to clear Tran of wrongdoing last year, he returned to work as a homicide investigator. According to warrants filed in Alameda County Superior Court, Tran worked at least four cases involving kidnapping, murder, or attempted murder in 2023.

One was a February 15 incident where three OPD officers were allegedly shot at 10 times while investigating armed robberies. Two suspects, including a juvenile, were arrested after the shooting.

Tran also authored warrants concerning the February 24 murder of a man inside his friend’s apartment on 67th Avenue. According to the warrant, the suspect told OPD officers the victim had been keeping him hostage inside his apartment and that the shooting was in self-defense.

District Attorney Pamela Price has stated that her office is reviewing at least 120 criminal cases involving Tran with the assistance of the Northern California Innocence Project. However, the DA’s office has not given any further details about which cases it has concerns about.

The Alameda County Public Defender’s office is also scrutinizing Tran’s work, and according to court records obtained by The Oaklandside, the defender’s office has already zeroed in on several cases.

In one, Tran is accused of offering a witness money, job opportunities, and relocation to an exclusive beachside community on New York’s Long Island. In 2020, Tran and his partner flew to Trenton, New Jersey, to interview a woman, Shacree Stevens, who had accused her boyfriend, Atiba Barnes, of domestic violence. Stevens told the West Coast cops that Barnes had previously confided in her that he’d killed someone in Oakland years before moving to the East Coast.

According to a motion by Deputy Public Defender Daniel Taylor, Tran allegedly promised Stevens relocation money “to put her up in the Hamptons” if she would identify the killer. Stevens then identified Barnes in a photo lineup. Taylor alleges that Tran and his partner, who were designated as FBI agents as part of a joint cold-case taskforce formed in 2014, never identified themselves as Oakland cops and that they “repeatedly referred to themselves as federal agents who could provide her with numerous benefits, including money, jobs and employment opportunity, ability to relocate and inferences to the witness protection program.” This gave an inflated impression of their ability to help and coerced her to cooperate, Taylor wrote.

In another case, involving the 2013 murder of Donitra Henderson in North Oakland, the public defender’s office has accused Tran of building a homicide case around the statements of a witness who was previously a suspect in the killing and had fled the state.

Leonard Jones was charged for Henderson’s killing in 2016. The case against Jones, Assistant Public Defender Christina Moore wrote in a February 2023 court filing, is “eerily similar” to the case against Douglas and Hunter because it relies on the testimony of a single witness. That witness, Dominique Smith, fled California for the East Coast after speaking with another OPD investigator in 2013.

Tran took over the Henderson murder case and interviewed Smith in 2014, after Smith was arrested by U.S. Marshals on unrelated forgery charges. Smith’s arrest and transport to OPD headquarters were not recorded. According to the public defender, there was no “plausible reason” why Tran and his partner did not record their interactions with Smith while she was being driven back to Oakland.

Immediately after this unrecorded car ride, Smith blamed Jones for the murder. Moore, the public defender, wrote that this is “circumstantial evidence” that Tran and another OPD officer “told her what they wanted to hear from her during the transport so that once inside [the interview room] she immediately told them it was Jones who was responsible for Henderson’s murder.”

Alameda County Public Defender Brendon Woods sent a letter to District Attorney Price on March 13 asking for thorough investigations into alleged misconduct by several law enforcement officers in the county, including Tran. Woods highlighted two more cases where Tran allegedly “cut corners and broke the law.”

According to Woods, during the interrogation of Steven Buggs, a Black man who’d been arrested on suspicion of homicide, Tran told Buggs that even if he invoked his Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination and refused to answer questions, a jury of 12 “white dude” jurors would see him as a “big scary black guy.” According to Woods’ letter, Tran told Buggs, “By you not sayin’ anything, you might as well…squeeze that noose a little tighter.” Buggs was convicted after a trial.

In the case of Jonathan Weems, who pleaded guilty to manslaughter for a March 2012 killing, Woods accuses Tran of pressuring an eyewitness into fingering Weems in a photo lineup. And in the case of Tavares Williams, convicted in the October 2014 shooting death of Marlin McCray, Tran allegedly testified that he paid informants “regularly” and had a variety of arrangements with confidential informants, including a “mercenary contract” for people “just looking for cash.”

Buggs, Weems, and Williams are all currently serving state prison sentences.

Given the seriousness of the allegations against Tran and the number of cases involved, Cordell, the former head of San Jose’s Independent Police Auditor, said an outside agency like the state attorney general should take over any criminal or administrative reviews. “They need to serve warrants, they need to audit his finances, he needs to give up his informants,” Cordell said.

Alameda Public Defender Brendon Woods said examinations of past cases should go beyond Tran. “There should not only be an investigation of Tran’s actions but also of anyone who touched his cases—partners, supervisors, district attorneys, from 2011 onwards,” Woods said. “There are people who should have known about this.”

Meanwhile, Tran is pressing for his right to a speedy trial to clear his name.

“Phong Tran and his reputation have suffered extreme and undue harm,” Ganz, Tran’s attorney, wrote in court filings last week. “There is no basis for the charges. We believe they are not prepared to prove them.”

Correction: Steven Buggs did not plead guilty to murder, he was convicted at trial. And Leonard Jones’ case is still pending.