Retired Oakland librarian turned author Dorothy Lazard was at home tending to her garden when The Oaklandside visited her recently for an interview. Taking care of her garden is one of the things she wanted to do after retiring in December 2021. She also wanted to work on her then-unpublished manuscripts.

In the year and a half since her retirement, Lazard has accomplished both. Her garden is well-taken care of. And on May 16, her memoir, What You Don’t Know Will Make a Whole New World (Heyday), was finally published. She started writing the pages of what eventually became the book in 2017, a year before her 50th anniversary of living in California.

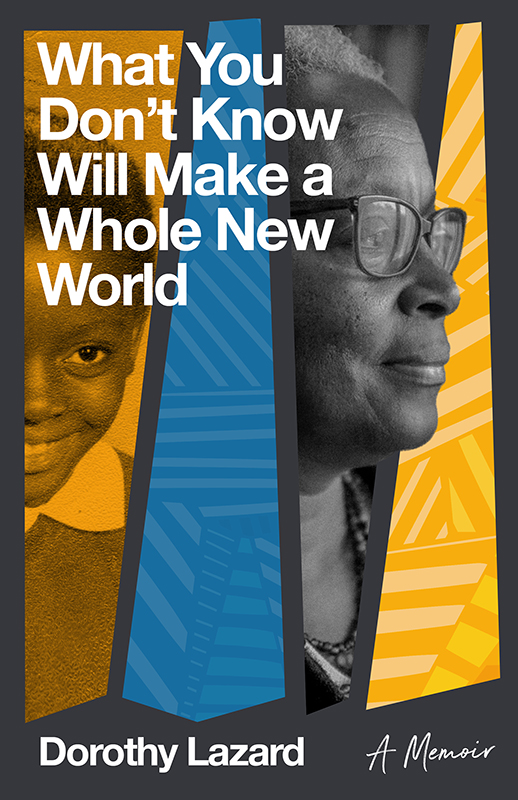

One of the photos on the cover is a portrait taken by The Oaklandside’s visual photojournalist, Amir Aziz; it was the feature image used for our story about her retirement. Lazard didn’t know then that the photo would also end up on the cover of her book. But ever since it was taken, it’s held a special meaning for her.

“This picture was so moving because I look like my mom. But my mom never got as old as I’ve gotten,” Lazard said. “Maybe she would have looked like this if she had lived this long. It was emotional when I first saw it.”

Lazard dedicated a section of her memoir to recounting the events that led to her family’s move from the Midwest to the Bay Area when she was a small child.

Lazard was born in St. Louis in 1959 to Lavurn (“MaDear”) and Jack (“Mr. Bear”) Lazard. Her mother’s ailing health, and the inability of her much older father to care for her and her brother, Albert, landed both siblings in an orphanage at an early age. This prompted Lazard’s grandmother, Ella (“Mam’Ella”) Baskin, who had a strained relationship with her daughter Lavurn and lived in San Francisco, to travel to St. Louis to take custody of both children and bring them, along with their mother, home with her to California.

Later in the memoir, readers also learn how Lazard’s fourth-grade teacher Mr. Eckhart, at Grattan School in San Francisco, played a pivotal role in developing her lifelong hunger for learning about history and geography.

“I’ve always loved geography because of him. You know, I was a map librarian at OPL because of him,” she said. “When I was told that I was going to be responsible for the maps collection and the history collection, I couldn’t have been more thrilled.”

Lazard wrote the memoir from the perspective of her younger self during the period when the family relocated from St. Louis to San Francisco in 1968 and later to Oakland, where she lived from 1970 to 1978, to show how those experiences shaped the woman she is today.

“I wanted to show how, when you’re a kid, you don’t have any agency; the only thing you have agency of is your brain,” she said. “Ultimately, this is a story about my relationship, not only with my mom and the rest of my family but with my brain. That’s how I could get power. That’s the story I wanted to tell.”

Lazard’s memoir takes a deeply personal turn in the retelling of her mother’s death on October 12, 1972, and how she navigated her grief:

“That day cleaved my childhood into two: the half where my mother existed in the world and the other half, which began that morning…What happens to a child without a mother?”

In addition to the sometimes painful family dynamics, Lazards’ book describes the challenges that came with growing up as a Black kid in Oakland in the ‘70s.

“I wanted to spend some time in the book showing that we were too young to be out at the marches,” she said. “But we were the ones who had to integrate the classes and had to be bussed to school.”

She describes the reasons why she moved to different neighborhoods and the things she learned about Oakland while riding the bus from west to east to get to Castlemont High School every morning.

Lazard credits “Aunt Clara” (what kids used to call the AC Transit bus back then) with helping her see how the demographics of the city were changing. At the time, white residents were moving out of East Oakland and other parts of the city to the suburbs, a phenomenon called “white flight.”

“There were still a fair number of white people in deep East Oakland when I was in junior high and high school,” she said. “And they just were not happy. I saw that when I would ride the bus.”

While living in West Oakland, Lazard also saw the landscape change: Victorian homes were demolished to give way for the construction of the Grove Shafter Freeway that connects the Nimitz Freeway (880) to the MacArthur Freeway (580); West Oakland residents left in despair by broken promises of new supermarkets, affordable housing, and jobs; and the construction of City Center, which made many small mom-and-pop businesses disappear.

“I put the history in there, not just because I’m a history nerd, but because that’s what the city taught me,” she said. “That’s the part of the book I enjoyed writing.”

Lazard’s work as a librarian, her charisma, and her expertise have gained her an online following. Years ago, fans started the #DorothyLazardFanClub. She still isn’t used to the notoriety.

“I became well known through people like you and [journalists Pendarvis Harshaw and Alexis Madrigal], but people don’t know how I became that well-known librarian,” she said. “Or what did you guys say? Legendary.”

At last month’s Bay Area Book Festival, she said attendees came up to her quoting lines from the book. At the same event, John Freeman, a writer and the executive director of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, said that her memoir didn’t read like it was her first book but more like her seventh. “That was an amazing compliment,” she said.

It won’t be long before Lazard publishes more books. She’s currently working on two manuscripts while also on the road promoting the memoir.

“My hope for the book is that people get a different perspective on Oakland and understand that you could come from a humble background and have a successful life,” she said. “I want them to celebrate Black girlhood, especially the story of a kid of color finding a way to empower herself. It’s important to find ways for kids to empower themselves. That’s one of my biggest hopes.”

Correction: the Grove Shafter Freeway connects the Nimitz Freeway (880) to the MacArthur Freeway (580).