On a typically chilly Oakland winter evening, when fog obscures vistas and frigid air seeps into poorly insulated homes, there can be nothing more soothing than huddling around a fireplace with friends or family. Across the city, many residents light up logs on these nights, ushering holiday spirit and warmth into their homes.

Wood burning is also the largest source of air pollution in the winter. Smoke from fireplaces and fire pits can leave neighbors with watery eyes and scratchy throats and exacerbate chronic health conditions like asthma.

In 2008, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (the public agency regulating air pollution locally) adopted its “wood burning rule,” urging residents to light fewer fires and keep the air cleaner and healthier. On “Spare the Air” days, when poor air quality is forecasted, it is illegal to use fireplaces and other wood-burning devices. Anyone can file a complaint if they notice smoke on these days, and if you’re caught in violation of the policy you can face fines up to hundreds of dollars.

Have the Spare the Air campaign and wood burning rule worked? Are Oaklanders aware of the dangers of wood smoke, and have they stopped using their fireplaces so much?

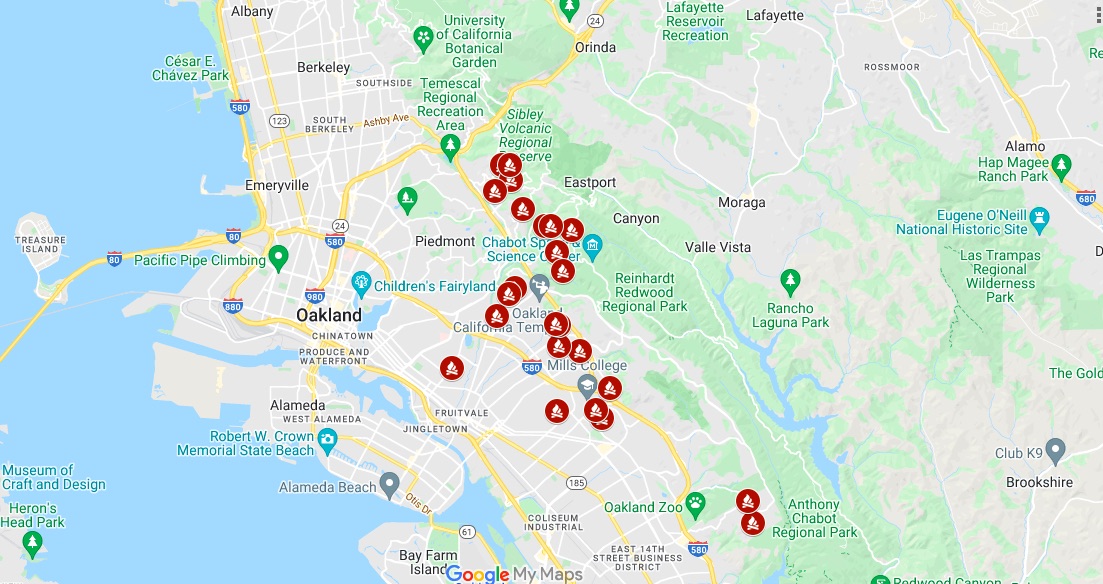

The Oaklandside reviewed 14 years of complaints and violation data, obtained through a public records request. We found that local complaints and violations were heavily concentrated in the Oakland hills.

The 1,255 complaints filed in Oakland since 2008 vastly outnumber the handful of citations issued in the same time period, raising questions about the effectiveness of the enforcement method, and about the level of awareness around the dangers of wood-burning.

Surveys also suggest that most residents haven’t changed their behavior over the years—contributing to poor air quality caused by increasing wildfires.

“On a cold winter night when the air is not mixing, it’s not nice to your neighbors to light a fire,” said Allen H. Goldstein, associate dean for academic affairs at UC Berkeley’s Rausser College of Natural Resources. “That’s the basic message.”

Wood-burning is the biggest source of particulate pollution in winter

During the winter months, the region experiences frequent “temperature inversions,” where a layer of warm, stagnant air creates a lid that causes toxic emissions to settle closer to the ground. These inversions cause those hazy winter days common in the Bay Area. There isn’t enough energy from the sun to heat the ground, or enough air to disrupt the inversion. So when pollution accumulates from fireplaces and the like, it sticks around instead of dispersing.

Some areas, like the Oakland and Berkeley hills, sit above the inversion. Smoke settles much lower, mostly affecting the flatlands, Goldstein said. “The problem is more persistent the lower you are,” he said.

But the overwhelming majority of both wood smoke complaints against households and violations are concentrated in the Oakland hills. Less densely populated areas with more single-family homes and at higher elevations topped the list of complaints reviewed by The Oaklandside.

This could be due to the higher prevalence of fireplaces in the hills, compared to flatter neighborhoods where there are more apartment buildings and newer construction. The Bay Area has a ban on installing fireplaces in new homes. Residents in the hills may also be more sensitive to woodsmoke and more likely to file a complaint, since those neighborhoods are prone to wildfires.

Wood-burning complaints and enforcement are concentrated in the hills

Data obtained from the air district shows there is a gulf between the number of woodsmoke complaints filed and violations issued. In Oakland, 25 fines have been issued compared to 1,255 woodsmoke complaints since 2008, the year the ban began on Spare the Air days.

Some residences in the hills were repeatedly complained about. One property that backs up to Joaquin Miller Park had 28 complaints lodged against it over a five-year period. (It is unclear if the same person filed all those complaints, or if several neighbors rang the alarm.) The 94611 ZIP code—Glen Highlands, Montclair, Piedmont Pines, and other neighborhoods above Highway 13—had the highest number of both categories, with 302 complaints and 10 violators.

The upper Dimond, Redwood Heights, and Oakmore area—94602—followed, with 197 complaints and five violations found. In other areas, complaints went nowhere. No violations were issued to residents of 94609 in North Oakland, despite the ZIP code being the third most complained about.

The other two ZIP codes in the top five in terms of complaints were: 94610 (Grand Lake/Adams Point/Trestle Glen/Crocker Highlands) with 117, and the East Oakland hills area code of 94619, which had 105.

Bay Area-wide, 1,827 violations have been issued and more than 30,000 complaints made since the start of the wood burning rule. Some tiny towns had double or triple the number of violations compared to Oakland, a city of about 440,000 people.

Forest Knolls and Woodacre, small Marin County communities less than three miles apart and set against an open space preserve, saw 62 and 58 violations respectively. There have been 1,272 woodsmoke complaints since 2008 in Forest Knolls, which has a population of approximately 1,770.

Kristine Roselius, spokesperson for the Air District, said topography has a lot to do with the volume of complaints in a given area.

“When just one person is burning wood in a neighborhood that might have more stagnant air, we’re likely to get more complaints about it,” Roselius said. “In Marin County, there may be hundreds of calls about one address.”

El Sobrante, Martinez, Fairfield, Pacífica, and Montara—all smaller than Oakland—also had more violations. Surprisingly, San Francisco had only two.

When is the wood-burning policy enforced?

If someone logs a complaint about a neighbor’s wood-burning behavior, it’s far from certain that it will result in a consequence for the resident who was using their fireplace illegally. While the agency has a cadre of patrol officers, they can’t rush out the moment a complaint is filed to confirm that illegal wood-burning is occurring, said Roselius. Instead, they monitor areas that produce a “high volume of complaints” and head there on a following Spare the Air day.

Wood smoke in Oakland: FAQs

“Our inspectors have to verify a complaint—they have to actually witness the burning—then we send a notice of violation in the mail,” said Roselius. They might also see smoke emerging from additional residences where complaints have not been logged, and those households can receive notices as well. Each address that’s the subject of a complaint receives a packet of information on the wood burning rule and the health impacts of wood smoke, regardless of whether the complaint is verified, however.

Residents who receive violation notices can choose whether to take a class about wood smoke or pay $100. The fine for the second violation is a much steeper $500, and the amount increases from there.

Notably, the Air District issued no violations in Oakland in 2021. According to Roselius, that’s because there were only five Spare the Air alerts that year, and they were in August due to wildfire smoke. Residents were less likely to have fires going during those warm, smoky summer nights.

More people are aware of the dangers of wood-burning. But have they stopped doing it?

In the years since the Spare the Air campaign launched, residents in the Bay Area—home to 1.4 million fireplaces and woodstoves—have become far more familiar with the dangers of wood smoke. But it’s less clear whether this knowledge has prompted people to burn wood less frequently.

Each year since 2008, the Air District has enlisted a San Diego-based research firm to survey Bay Area residents’ opinions about wood smoke. The most recent survey, conducted in 2020, found that 82% of adults perceive negative health effects associated with breathing wood smoke. This was the highest level of awareness ever tracked by the annual survey, which found that only 69% of adults knew about the health risks in 2008. However, there are still disparities based on education level and language.

“Certainly there’s a much better awareness of wood smoke being harmful,” said Roselius. “In 2008 that knowledge was not there and we’ve worked to build that since then. We have our advertising campaign but we also go door-to-door in neighborhoods where we see lots of complaints.”

Over the same time period, Bay Area wildfires have increasingly choked the region with smoke that causes headaches, burning eyes, and other health issues, likely contributing to the increased recognition of the health impacts of burning wood.

Awareness of the wood burning rule has also increased, growing from 59% to 68% of survey respondents between 2008 and 2020.

“It’s a spectacular success story in the Bay Area how quickly the public has learned about the dangers of wood smoke and has changed their behavior as a result,” said Roselius.

However, it’s unclear just how much behavior has changed. Among households that have a wood-burning device, like a fireplace, 22% of survey respondents said they refrained from using them in 2020 because of the Spare the Air alert program or health concerns.

But that statistic has remained virtually unchanged since the implementation of the wood burning rule and launch of the survey in 2008, when 23% of respondents gave the same answer. In fact, it dipped in 2019, when just 8% of respondents said they’d refrained from wood-burning for those reasons.

As March gets underway, the threat of particulate matter pollution will wane, with fewer fireplaces in effect and fewer temperature inversions trapping smoke at the surface.

But summertime brings its own air quality risks. On warm days, ozone pollution, commonly known as smog, is the greatest source of poor air quality, often caused by car emissions.

Wood-burning is still not recommended, though, and while fireplaces typically sit untouched on warm nights, other devices are still common in the summer. Those backyard fire pits and beach bonfires? They may not be as innocent as they seem.