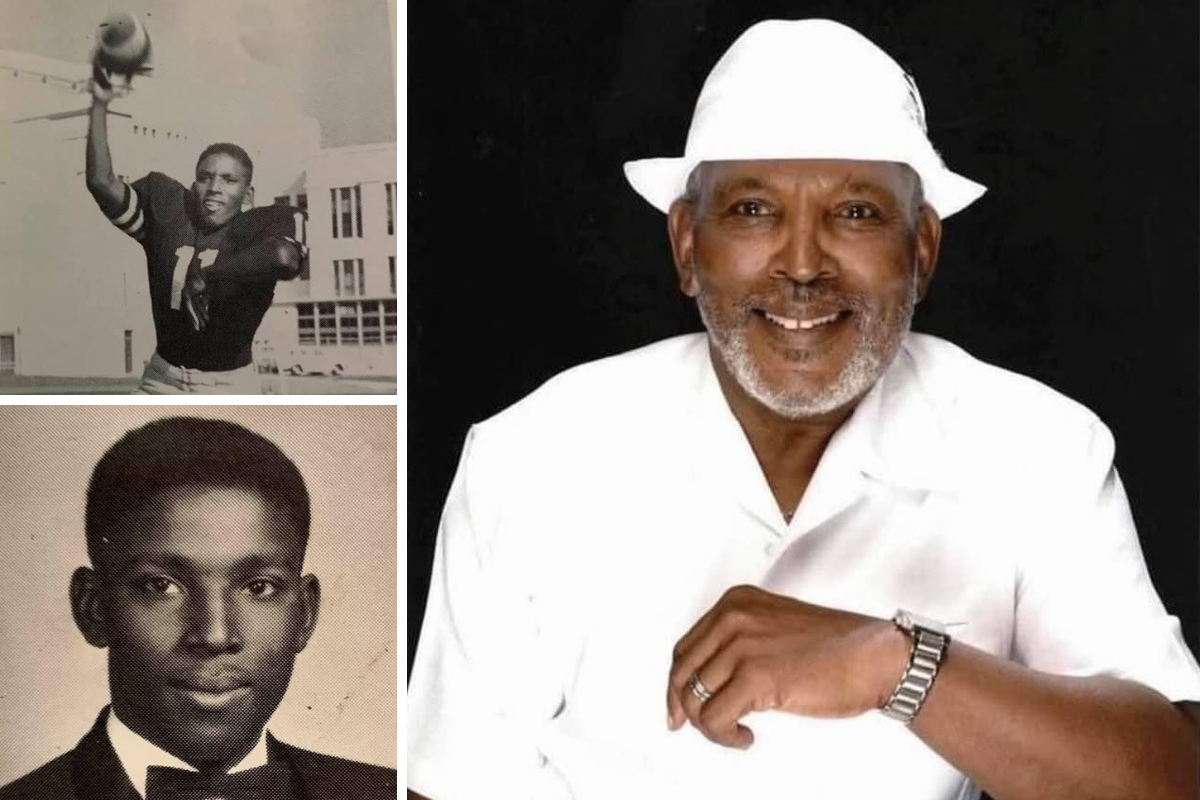

The Oakland Tech High School community lost an icon on Friday, March 19, with the passing of a lifelong Oaklander, Wayne Brooks.

Raised in Oakland’s Hoover-Durant neighborhood, now known as Hoover-Foster, Brooks built his life around Oakland Tech. Described by friends as a born leader with a magnetic personality, he was a star athlete and the school’s starting quarterback by the time he was a sophomore. He graduated from Tech in 1965 and by 1971 had joined the school as a teacher. He would stay there—teaching Black history, U.S. history, American government, economics, and coaching sports—until his retirement in 2011.

His daughter, Breanna Brooks, spoke to The Oaklandside briefly by phone and recalled how it felt to be a student at Tech when her dad was on campus. “I couldn’t wait to get there to be with him. I just remember everybody knowing me as Mr. Brooks’s daughter. I enjoyed going to see him. I’m a daddy’s girl, and I always had to share him at school.”

Referred to affectionately by many as simply “Mr. Brooks,” his passing solicited an outpouring of remembrances on social media from former students and colleagues. Their commentaries, and several interviews conducted by the Oaklandside with people whose lives he touched, draw a picture of an educator whose joy was infectious, who cared deeply about the emotional well-being of his students, and who was a mentor and inspiration to his peers, with whom he maintained lasting and heartfelt relationships.

“He was a father figure to everyone”

Leon Sykes attributes his decision to become an educator to Mr. Brooks and several other Black teachers who he had as an Oakland Tech student in the early 2000s. Sykes, who also goes by DNas and is recognized for his radio and podcasting work, as well as his lifeguarding at various public pools around town, currently teaches audio production and media arts to 10th graders at Fremont High School.

Like so many other Tech students over the years, Sykes said Mr. Brooks was more than a teacher—he was family.

“Mr. Brooks, I called him Uncle Wayne, because we legitimately were all his kids,” said Sykes. “He was a father figure to everyone and he was a male figure that you needed in the schoolhouse. Then I found out that my uncles and Mr. Brooks were all frat brothers, and I was like, well, you have no choice!”

Mr. Brooks would open up his classroom nearly every day at 7:30 a.m., recalled Sykes, and he and a lot of the young men at the school would show up.

“Some of the homies, you know, we would go and sit in his class before school started. I wasn’t the greatest student, academically. I wasn’t as invested in school, but in his world history class, I actually did the work,” said Sykes. “Just to be in his presence, you know—he demanded excellence, and not necessarily in the sense of a lecture, but in letting you know what the real world is going to be like, and that where you’re at right now, you’re not always going to be there. That in itself really pushed me to do better.”

Mr. Brooks was the rare teacher, said Sykes, who created spaces for students to have real, personal conversations about the big questions in life. When Sykes was a sophomore at Tech in 2001, he recalled watching the events of September 11 unfold on a TV screen in Mr. Brooks’ classroom. The memory stuck with Sykes, as much due to how Brooks handled the moment as the catastrophe itself.

“During that time we didn’t always have the introspective conversations that you may see with young folks now, where they’re intimate and everything, and they have access we didn’t necessarily have,” said Sykes. “So for him to have that door open meant something. We were actually able to watch it and kind of break it down.”

Now that Sykes has students of his own, he draws on those same qualities he admired so much in Mr. Brooks.

“It’s not always just, ‘Okay, we have to write a story and we have to record the story,’ as much as, ‘Let’s talk about who you are, let’s connect this to your individuality.’ I could have done a lot worse in life. Mr. Brooks taught me that there’s always a chance to grow, and that’s what I’ve learned from him: that even your students that you may consider to be the most problematic, are sometimes the ones that you need to focus on more, give them support, and push them to be better.”

“That’s who he was and who he always will be. It wasn’t just teaching. He was honestly a part of our lives, a person that was the walking example of a mentor, and somebody who legitimately cares about his community.”

“Kids just flocked to him”

Yetunde Reeves was still getting her feet wet as an educator in Oakland in 2002 when she met Mr. Brooks. Reeves was teaching at McClymond’s High School in West Oakland that year but figured she could help her students and earn some extra money at the same time by also teaching summer classes at Oakland Tech. By then, Brooks had been teaching at the school for three decades.

That Brooks was teaching summer school, in the first place, left an impression on Reeves. “You spend summer with kids and you just do all that you can do to support young people, and that was Mr. Brooks. He didn’t have to work summer school by that time, I’m sure. It’s a choice to spend your summers with young people, and I think that was a significant example for younger educators—that the work isn’t a tenure assignment.”

Mr. Brook’s commitment to his students was reflected back in how they responded to him as an educator, said Reeves.

“Kids respected him. He was a very jovial, kind, supportive teacher. He was seen as a father figure, or an uncle—a no-nonsense person but someone who had expectations for young people, and was going to support them getting to the next level for themselves,” recalled Reeves. “He was the teacher that walked around and checked on everybody, you know? All the kids just flocked to him. He was a larger-than-life personality.”

Reeves credits her four years of teaching social studies and U.S. history at summer school alongside Mr. Brooks as one of the experiences that inspired her to stay the course and pursue a lifelong career in education as a teacher and school administrator. She would eventually go on to become the principal at McClymond’s High School in West Oakland and lead a variety of other successful schools in Oakland and elsewhere. Reeves, now a high school principal in Baltimore, Maryland, says she’s still applying lessons learned from her days in Oakland, surrounded by standout educators like Mr. Brooks.

“We’re doing some work [in Baltimore] around creating an academic culture—really pushing kids towards college—and I’m able to build on the work that we did. That’s really been my life’s work, and I’m continuing that on the East Coast with lots of lessons from Oakland.”

After Reeves left the district in 2010, Mr. Brooks made a point of keeping in touch with her over social media. The correspondence was consistent, said Reeves, right up until the last couple of years.

“It wasn’t more than just, ‘How are things going? Hope you’re well,’ you know, just those general check-ins. But of all the adults in Mr. Brooks’s life—I’m sure he had a lot of people that he came in contact with—it just always made me feel really special to hear from him regularly. It was just really touching.”

Reeves, who grew up in Palo Alto and taught briefly in Los Angeles after graduating from UCLA before moving back to the Bay, considers herself fortunate to have landed at Oakland Unified School District early in her career, at a time when she was looking for role models.

“I personally found a lot of inspiration in seeing veteran Black teachers,” said Reeves. “Mr. Brooks was part of a generation of educators who had been in Oakland as students. I’m not from Oakland, but it was amazing to just be a part of a city where so many educators were from the community. Having educators who devote their entire life to young people is what we need more of. I’m a lifelong educator, Mr. Brooks was too, and I think that creates a sense of community and signals to kids that they’re important, that people are willing to invest time, energy, love, and compassion into them. So I kind of grew up as a practitioner in Oakland and it was a phenomenal experience, because of educators like Mr. Brooks. He’s like the gift that keeps on giving.”

“Wayne was one of us”

When Mr. Brooks passed, Marty Price didn’t just lose a respected former colleague. He lost a lifelong friend. The two had grown up together in Hoover-Durant and attended high school together at Tech. Price says that even back in high school, Brooks had a positive energy that rubbed off on those around him.

“Teachers always loved Wayne; they didn’t always love me,” laughed Price. “And our peers always loved him. He was everybody’s brother, everybody’s uncle as an adult, everybody’s pseudo poppa, you know. Wayne was a quarterback and a leader. He was just good with people. There’s something made in some people that can’t be taught, and with Wayne, teaching was a calling. He was more than a teacher, he really was.”

Price’s own journey as an educator began in 1984, at age 40. He’d been working for years in the trade show industry and was volunteering on the side as a youth sports coach on his children’s teams. Eventually, he realized that working with kids was a calling. He got his teaching credential and took a variety of jobs at Oakland schools, eventually moving into administrative roles. He reunited with Mr. Brooks at Tech as a school site administrator in 2000, and the two worked there together until 2005. Price describes the period as “the best five years of my education career.”

“His room was a refuge for kids, some of whom didn’t have homes to go to. Mr. Brooks, his classroom was really more than a classroom. Kids would go there before and after school. Wayne always welcomed them and always had something good to say. He’d come up to kids and if they were having a problem—we were both huggers, and I know you can’t hug kids now—but he would comfort kids in distress, even if they weren’t in his class. I grieve, knowing that he gave so much to Tech.”

Price noted that he and Brooks came up during an era when Black teachers were far and few between, and those who were there were expected to go above and beyond. “We grew up at a time when we didn’t have a lot of Black teachers. The ones we did have had master’s degrees from Columbia, while the white teachers, by and large, had bachelor’s and a credential,” he said. “I’m not deriding that—that stuff worked out too. But our Black role models had to be the best of the best.”

Mr. Brooks, said Price, was among that group. He personified the sense of community embodied by Oakland Tech and was one of countless influential but unheralded educators to have a lasting impact on Oakland’s kids.

“Everybody thinks that we have a public face of Oakland public schools in Tom Hanks, but we also have a public face that is not known, and it’s guys like Wayne—people that grew up in Oakland public schools and have dedicated their lives to kids,” said Price. “So it’s a big loss for those of us old-timers who grew up with him.”

“Wayne was one of us. He represented the neighborhood, and he understood that Tech was more than a school. He understood that Tech was a community.”