Many East Bay residents are justifiably proud of the athletes who grew up here. Some fans can rattle off the Hall of Famers in the major sports, including Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Willie Stargell, Joe Morgan, Ricky Henderson, Dave Stewart, Gary Payton and Jason Kidd.

In almost every case, the families of these star athletes moved to the East Bay flats from southern states during or shortly after the Second World War, when defense jobs in Oakland and Richmond were plentiful. Segregation often kept Black families in those neighborhoods, even after California passed its fair housing law in 1963.

Not all of the East Bay’s notable athletes were Black — Billy Martin, for example, who was white, attended Berkeley High School before signing with the fabled New York Yankees — but the influx of African-American families to Oakland, Berkeley, El Cerrito and Richmond supercharged the local sports scene even as it transformed its politics.

These Hall of Famers were determined as well as talented. Russell overcame every racial barrier to become a dominant NBA player and the first black coach in any major sport. After his stellar career as a player, Robinson was named the first black manager in major league baseball. Although Stargell was beloved by his fellow players, he never forgave the Pittsburgh Pirates for denying him a shot as manager. Morgan was considered a troublemaker in Houston but made eight consecutive All Star appearances while playing for the Cincinnati Reds. Henderson was famously cocky, and Stewart was known for his death stare from the mound. Payton attributed much of his success to mental toughness, a quality that Kidd admired and imitated. If these athletes had anything in common apart from their prodigious talent, it was their intensity, confidence, and resolve.

Less renowned East Bay athletes also broke new ground. Old-timers may recall that Pumpsie Green, a graduate of El Cerrito High School, was the first African American to play for the Boston Red Sox, the last major league team to integrate. Curt Flood, who played in the same outfield at McClymonds High School with Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson, challenged baseball’s reserve clause, which essentially made every major league player the property of the team that signed him. Flood’s legal challenge failed and ended his career, but the reserve clause was abolished six years later. A three-time All Star and seven-time Gold Glove recipient, Flood posted a .293 career batting average and held the major league record for stolen bases until Ricky Henderson claimed that title. That Flood has not been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame shows that the sports establishment does not always celebrate its iconoclasts.

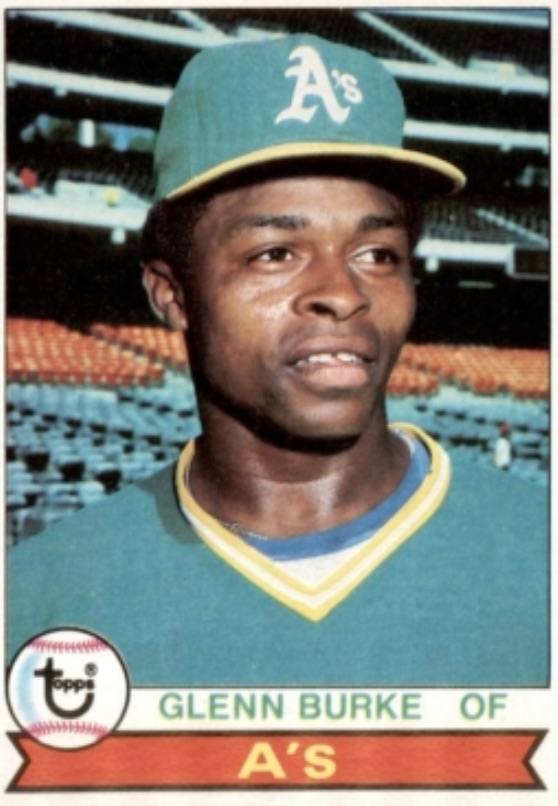

In his new book, “Singled Out,” sportswriter Andrew Maraniss showcases the life and times of Glenn Burke, one of the most extravagantly gifted athletes to emerge from the East Bay.

Born in 1952, Burke grew up in North Oakland and South Berkeley. His father boxed in the Navy, worked in the Oakland shipyards and quarreled with his mother, a nurse’s aide who left her husband the year Glenn was born. Burke honed his basketball skills at Bushrod Park in North Oakland before attending Berkeley High School.

Well under six feet tall, Burke ran 100 yards in 9.7 seconds, bench pressed 350 pounds, and had great leaping ability. In 1970, he led an undefeated Berkeley High basketball team to a Northern California championship and was named the region’s player of the year. After graduating, he played basketball and baseball at Merritt College, where his speed, throwing arm, and home-run power drew the attention of scouts. Although he had not given up on his hoop dreams, he signed with the Dodger organization in 1972. Baseball offered a quicker path to success, and the $5,000 bonus was decisive.

In the minor leagues, Burke became known as a charismatic if difficult clubhouse personality. He was also a sharp dresser, impressive dancer, and feisty competitor. Less well known was the fact that he was gay. After the 1974 season, he had his first sexual experience with a man, one of his former teachers in Oakland. While playing AA ball in Connecticut, he began visiting gay bars. In the offseason, he returned to the Bay Area and explored the Castro district.

In 1975, Burke made it to squeaky-clean Los Angeles Dodgers, where he played behind outfielder Rick Monday. He was popular in the team’s otherwise tense clubhouse, but coach Tommy Lasorda disapproved of Burke’s friendship with his son, whom Lasorda strenuously denied was gay. When Burke’s sexuality became an open secret, the front office offered him $75,000 to marry a woman. The offer was delivered by general manager Al Campanis, who would later be fired for claiming on national television that African Americans lacked the skills to manage baseball teams.

Traded to the hapless Oakland A’s

Shortly after rejecting the Dodgers’ offer, Burke was traded to the hapless Oakland A’s. Burke welcomed the return to the Bay Area, not least because it put him closer to the Castro. But he did not hit it off with A’s manager, Billy Martin, who called him a “faggot” in front of his teammates. After Martin sent him back to the minor leagues, Burke retired at age 27. He never lived up to his vast potential, but many of his teammates thought he was driven out of baseball because of his sexuality.

No longer concerned about shielding his private life, Burke became a hero in the Castro.

“I just started living my life,” he said, “being me.”

Admired for his physique and engaging personality, Burke developed a network of friends. Still focused on sports, he also led his gay softball team to a league championship and won gold medals in the first Gay Games. A friend proposed a magazine profile that would acknowledge Burke’s sexuality even more explicitly. After Inside Sports ran that article, Bryant Gumbel interviewed Burke on The Today Show. Burke expected the media interest to refresh his career. That never happened, but he would forever be considered the first openly gay player in major league baseball.

As the 1980s wore on, Burke’s life spun out of control. His drug use became a problem, and his friends died in droves when AIDS ravaged the Castro. One of his sisters was stabbed to death in 1983, and, four years later, Burke was struck by a car while crossing a busy intersection in the Castro. He was knocked 70 feet, and his legs were broken in three places. Now even his softball career was over. Worse, he had no money, job or permanent home. He wandered the Castro, began to smoke crack and served a 16-month term in San Quentin State Prison for drug possession. In 1993, he was diagnosed with AIDS, and after a period of intense suffering, he died in 1995.

“Singled Out” tells Burke’s story briskly and skillfully. Its plentiful helpings of social history — not only about the East Bay, but also the Castro — distinguish the book from the heartbreaking 2010 documentary film, Out: The Glenn Burke Story, that covers much of the same ground.

Given the fact that “Singled Out” targets young adults, Maraniss’s attention to social context is laudable. (For those born in the 21st century, Burke and his world are ancient history.) Moreover, the period detail never impedes the story or shies away from difficult topics. On the contrary, the capsule histories are consistently clear, measured and on point.

As someone who teaches this material to college students, I appreciated Maraniss’s adroit narration, but my interest in Burke was also personal. Having grown up in the East Bay almost a decade after him, I was aware of his legend but never saw him play. I was eager to see a full-length treatment of Burke’s immense talent, thwarted career, and personal challenges.

Despite the tragic ending, “Singled Out” is by no means gloomy. Maraniss emphasizes Burke’s ebullient personality along with his professional and personal setbacks. He also inserts several fun facts about the Oakland A’s organization, which at that time employed clubhouse attendant Stanley Burrell and ball girl Debbie Stivyer. Burrell parlayed a chance encounter with A’s owner, Charlie O. Finley, into a rap career as MC Hammer. Stivyer, who presented milk and cookies to umpires between innings, started Mrs. Field’s Cookies. Only Maraniss’s emphasis on Burke as the inventor of the “high five,” which Burke bestowed on teammate Dusty Baker after an important home run, seems slightly overdone. Then again, I aged out of the book’s target market four decades ago.

Above all, “Singled Out” presents the clash between Burke’s sexual identity and the norms of professional baseball. Of course, Burke was not the only gay player in the major leagues, much less in professional sports. Even so, no active major league player has come out since Burke’s announcement four decades ago. As a result, his story resembles a cautionary tale rather than a progressive milestone in the tradition of Bill Russell, Frank Robinson or Curt Flood.

Major league baseball is still not ready for Glenn Burke, but the time may be right for Maraniss’s deft biography.