Longtime residents of Oakland’s Golden Gate neighborhood have a nickname for the sprawling intersection of Stanford and San Pablo avenues. “Holy corner.”

In fact, all four corners at this convergence are owned by spiritual organizations. Three of the properties belong to the SYDA Foundation, a New York-based nonprofit that operates ashrams and meditation centers around the country, including the Siddha Yoga Ashram in Oakland. The fourth corner is the Star Bethel Missionary Baptist Church.

But SYDA’s presence in Golden Gate reaches far beyond the intersection. The foundation and associated people own some 30 properties in the area just south of the ashram, the group’s main building.

About half of these properties are vacant—empty houses, storefronts, and undeveloped lots, some obscured by fences, and some unoccupied for years or even decades.

Neighbors who’ve become aware of the ashram’s property holdings are surprised by how much the organization owns, and the group’s real estate portfolio has increasingly become a topic of discussion among Golden Gate residents.

“Over time, we’d hear, ‘Oh, that’s an ashram property.’ ‘That space is owned by the ashram,’” said Alex Bernardin, who moved to Marshall Street, around the corner from the ashram, nine years ago. “We would get a sense of, oh, they’re sitting on a lot of land.”

Vacant properties have become a hot topic in Oakland in recent years, as city leaders and activists scour for low-hanging and low-cost solutions to the local housing crisis. Voters in 2018 passed Measure W, a tax on vacant properties, hoping the $6,000 annual fee would pressure the owners into renting out their unused units or developing housing on their fallow parcels.

However, Oakland’s vacant property tax has not been applied to the ashram’s properties, and the group has received religious tax exemptions on much of its real estate in the area, according to public records.

Several neighbors who’ve recently contacted or spoken with The Oaklandside expressed frustration that, as homelessness has exploded in North Oakland and new cafes and shops have sprung up on other parts of San Pablo, so much property on these blocks remains unoccupied and stagnant. For some, burgeoning public safety concerns in the neighborhood have only heightened their focus on these properties.

The SYDA Foundation did not respond to many requests for interviews, but a local representative for the organization sent a statement saying the group is working with neighbors to improve conditions at its properties.

Many residents emphasized that their irritation is with the unused land, not with the local ashram members who’ve long lived in the neighborhood or visit the meditation center, who have no involvement in property decisions.

These neighbors are hoping the organization will eventually reactivate the boarded-up shops and paved lots. But with decision-makers on the other side of the country, and years of status quo, it’s not clear if the will is there.

“This could be a vibrant neighborhood,” said Bernardin. “From a housing supply standpoint, those are spaces that could be lived in. Meanwhile, people are being pushed off the ladder, onto the streets.”

An unlikely, but welcome, arrival in North Oakland

The ashram is often credited—by its members and outsiders alike—with helping turn around the Golden Gate area during a tough time. It took over the old Stanford Hotel, which had become dangerous and decrepit and closed in the early 1970s after a 17-year-old was shot and killed inside of it.

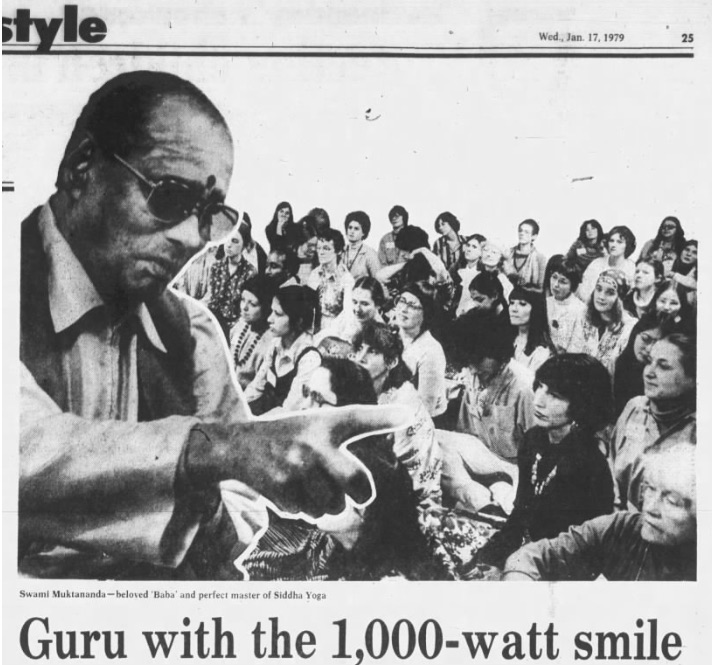

Around this time, Indian Swami Muktananda Paramahamsa, called Baba by his fervent followers, began spreading his Siddha Yoga teachings in the west, opening ashrams, mediation centers, and chanting and meditation groups.

“Rooted in the wisdom of India’s ancient sages, scholars, and philosophers, Siddha Yoga welcomes people of all faiths and cultures, teaching that divinity lies within each human being,” the Oakland ashram website says. “Yoga” in this case is not limited to Hatha yoga—the physical practice—but a broader set of spiritual practices and tools.

“Yoga means union,” said Carolynn Melchert, a longtime Oakland ashram member who moved to Marshall Street in 1988. “And it’s about the union of your spirit and your whole self with the divine.”

Muktananda bought the shuttered Stanford Hotel in 1975, opening what would become one of the first and largest ashrams of the SYDA Foundation—short for Siddha Yoga Dham of America. The organization is headquartered in the Catskill Mountains, and now led by Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, who took over in the 1980s when her guru Muktananda died. There are dozens of Siddha centers around the globe.

The organization’s arrival in Golden Gate changed the face of the neighborhood. Since World War II, that part of North Oakland had been a diverse and predominantly Black neighborhood, initially with a thriving business district fronting San Pablo and Stanford avenues.

In 2015, cultural researcher and North Oakland resident Sue Mark interviewed Golden Gate residents about what the area was like in decades past, for a project called Commons Archive. (The interview collection is available at the Golden Gate branch library.)

Joanne Dickerson-Harper, an interviewee whose family moved to the area in 1948, said they “liked the fact that we had grocery stores, we had department stores; everything was centrally located.”

But like much of Oakland, the neighborhood was experiencing systemic disinvestment by the government and landlords, writes Mitchell Schwarzer, author of Hella Town. Golden Gate was zoned for industrial uses by the city, despite being largely residential, according to Schwarzer. Once the streetcar lines closed and highways were built, traffic was diverted off of San Pablo, and retail fled with it.

By the time Robin Freeman moved in around 1978, the neighborhood “was in decline, and a little bit rough,” he told The Oaklandside. There were “some drug houses, but also families that had been here for a long time. It was working-class,” said Freeman, emeritus chair of Merritt College’s environmental program and co-director of the David Brower, Ronald Dellums Institute for Sustainable Policy Studies.

One of Freeman’s favorite haunts was Sue and Gene Cafe, “a wonderful breakfast place” in what’s now a vacant SYDA property. Coffee cost a quarter and you had to “yell your order.”

Longtime residents initially viewed the ashram, and its predominantly white devotees, as a curiosity, according to a 1983 Oakland Tribune article.

“When the smiling, gentle-mannered, reddish-orange clad strangers with the Hindu red bindi—or third eye, inner eye, as they are commonly called—moved in, it baffled many residents of this largely black, working class community,” the article says. But over the following years, neighbors began to embrace the newcomers, who planted flowers, maintained public landscaping, renovated the rundown hotel building—and brought a sense of safety and peace to the neighborhood, several longtimers are quoted as saying in the story.

Citing the ashram renovation and other nearby projects, the city councilmember at the time, Marge Gibson, predicted that San Pablo would undergo “the same renaissance as did Piedmont and College avenues.”

By the late 1980s, there were some 200 households with ashram members living within a half-mile radius of the Stanford Avenue center, said Seth Melchert, who became one of them when he and his wife Carolynn bought a house on Marshall Street in 1988. This was the heyday of the Siddha Yoga Ashram in Oakland.

“There was such an impulse, such a surge, such a movement,” around the ashram and guru Muktananda, Seth Melchert said. “He had this undeniable, powerful impact on people. They’d have these mystical experiences just by him looking at them or touching them.”

It was a feeling of transcendence that could be associated with the counterculture movement of the era or psychedelic drug use, said Melchert, but was an experience more internal and spiritual for the participants.

A social scene developed around the Oakland center.

“We raised our kids with a whole gaggle of other kids who are all connected to the ashram,” said Seth Melchert. He and Carolynn Melchert spoke with The Oaklandside in their home, where a photograph of Gurumayi hangs prominently in the living room. Even after Muktananda died, the community continued to grow for another 20 years, he said.

“There was a tremendous vitality that brought together people of all walks of life,” said Seth Melchert.

The ashram also attracted high-profile devotees, including once-and-future Governor Jerry Brown and former Black Panther Ericka Huggins. Later, the anonymous ashram and guru featured in the book and movie Eat, Pray, Love was widely assumed to be a Siddha Yoga site in India and Gurumayi, though SYDA has tried to distance itself from the works. In the 1990s, SYDA was briefly embroiled in controversy after ex-members spoke out about alleged abuses by the organization’s leaders, which led to an investigative report in The New Yorker.

In the early 2000s, the ashram shifted to a more “internal” and “contemplative” focus, according to Melchert. The social scene aspect subsided, with devotees turning towards “the individual practices at the core of the teachings,” he said.

Neighbors said it appears that the ashram’s membership is waning, and aging.

“When I first lived in this neighborhood, properties were occupied by younger members,” said Marisa Villa, who moved to Golden Gate in 2000. She’s not an ashram member but rents a house owned by SYDA. “They might be experiencing a generational shift. Seasons change,” she said.

Villa said she has a “great deal of affection for what the ashram has tried to do—I remember San Pablo back in the day.” And she’s grateful to have had a stable, affordable place to live for two decades.

“The problem comes with the lack of usage,” she said. “There’s very little that happens on San Pablo because the ashram has a blank face along that side.”

Nonprofit tax exemptions on vacant properties

The hundreds of North Oakland residents once connected to the ashram had mainly lived in houses and apartments they owned or rented, not SYDA property. The foundation appears to have bought most of its property in the 1990s and early 2000s. Nobody is entirely sure why the organization acquired so much real estate in the area, or why it has let many of the houses and lots sit empty for years.

Multiple people interviewed for this story brought up a longstanding rumor that SYDA intended to develop a large campus on these properties. Some pointed out that the organization has bought up essentially an entire city block—the west side of San Pablo, stretching from Stanford to 55th, save for one or two small parcels.

Property decisions, according to local ashram members, are made by the board of trustees in New York.

The Oaklandside sent multiple requests for interviews to the SYDA board and national organization, as well as the Oakland ashram.

Judy Scott, who works for SYDA on its Oakland coordinating team, responded with a statement.

“As we continue resuming operations following the COVID closure, the Siddha Yoga Ashram in Oakland has been and will be engaging in the beautification and landscaping of SYDA Foundation properties,” she wrote in the email. She didn’t respond to a follow-up request for an interview.

When the late community organizer Josephine Lee spoke to Mark, the cultural researcher, in 2015, she said it “bugged” her that SYDA could let so much property sit there and not have to pay taxes. Lee co-founded the San Pablo Avenue Golden Gate Improvement Association and created a free Sunday jazz concert at the neighborhood library. She speculated that city officials won’t “touch [SYDA] because it’s a religious group and they’re afraid.”

The current city councilmember for the area, Dan Kalb, did not respond to requests for an interview. But other residents also told The Oaklandside that they think SYDA is either unmotivated to do anything about its empty parcels, or is intentionally sitting on them, because it’s exempt from taxes as a nonprofit and spiritual organization.

SYDA is not, in fact, off the hook for all property taxes. The organization pays tens of thousands of dollars in city and county parcel taxes each year. But it does get a pass on some forms of property tax—and it’s not completely clear why.

Property owners can get an exemption from the city of Oakland’s vacancy tax for a few reasons, including if they’re a nonprofit organization. SYDA did not pay the vacancy tax on any property, according to tax bills from last year. We were unable to determine whether Oakland failed to identify the parcels as vacant, or if they were identified but SYDA received the nonprofit exemption. The city declined to share this information, citing safety concerns around publicizing the locations of vacant properties.

SYDA did claim and receive a “welfare exemption” on many of its properties, allowing it to avoid paying many property taxes. This broader exemption is for properties owned by a nonprofit and “used exclusively for charitable, hospital, or religious purposes,” according to the state. California determines whether an organization is eligible for the welfare exemption from local property taxes, and a county determines whether specific properties apply. The exemption doesn’t apply to special taxes and assessments, which the organization still has to pay.

Nine SYDA properties that are reportedly vacant—including five documented as vacant by the Alameda County Assessor—received the welfare exemption during the last tax year, despite seemingly having no use, let alone a charitable or religious use. The exemption on these nine properties applied to over $33,000 in taxes SYDA would have otherwise been required to pay last year.

The Oaklandside asked the assessor’s office for clarification on why these properties received the welfare exemption. A staff member responded that the office is “looking into this claimant’s exemption history.”

Other SYDA properties are in use. There are apartments rented to both ashram members and other tenants. There’s a commercial building rented to a bike shop and a salon. Some of the largely vacant parking lots and undeveloped lawns are used for occasional but significant ashram events, once or a few times a year according to neighbors. (These would still be considered vacant for the purposes of Oakland’s tax, which considers anything with fewer than 50 days of use per year “vacant.”)

Starting this summer, Golden Gate residents began meeting with each other about a range of concerns arising in the neighborhood, around safety, crime, and illegal dumping. Much of their focus has been on a homeless encampment on 55th Street, and people experiencing mental health crises on the streets. Also at the center of these discussions has been a long-vacant, deteriorating apartment building at the corner of San Pablo and 55th.

This property is not owned by SYDA directly. Instead, the owner is a trust in the name of the late Peter Sitkin, a well-known public interest lawyer who represented the ashram, and Janet Dobrovolny, local attorney who is a longtime ashram member and is listed on business records as a SYDA agent. She is the previous listed owner for two other properties now owned by SYDA, and currently owns another in-use rental property in the neighborhood. She didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

Oakland has received 20 complaints about the rundown corner building since 2019, records show.

“Owner has been unresponsive to many neighbor’s requests to clean up lot which is attracting trash, public defecation, rats, etc.,” one person wrote.

“Does College Ave have anything like this for this long of a time?” asked another.

This summer, the owner filed for a permit to demolish the structure, city records show. A yellow city notice posted on the property in early September said the building would come down in 30 days. The owner meanwhile sent a junk collector, according to neighbors. But the building still stands, and city records say the tear-down is “on hold” pending a site check.

Scott, the SYDA representative, said in the statement she sent The Oaklandside that she has been meeting with neighborhood groups to “see how we can continue to work together,” noting a “neighborhood cleanup and beautification project” scheduled for the end of the month.

Visions for a thriving Golden Gate

In her 2015 interview, Lee, the neighborhood organizer, said a group of residents had approached the ashram at one point, asking why they weren’t interested in building condos or the like on their properties. You could make some money, they reasoned.

Ashram leaders responded, “We’re not interested in making money,” according to Lee.

Other neighbors are wary of this sort of development. Another resident interviewed in Mark’s project, Fred Williams, criticized the high-cost, luxe apartment buildings springing up nearby along San Pablo.

“The wind don’t even blow here no more the same, since they put these big old buildings up,” he said. “They make it so out of reach that the average person can’t afford to be here.”

If SYDA suddenly decided to sell or develop its vacant lots, there’s no guarantee that the housing eventually built atop them would be priced affordably for the people struggling to stay in North Oakland, let alone the people living on the streets around the ashram. In recent years Oakland has crushed its targets for market-rate development, but lags significantly on affordable housing creation.

In Oakland’s new Housing Element, the official roadmap for building more housing throughout the city, two of the large, vacant SYDA lots are included on the list of sites where new homes could be built.

There’s also a growing movement—sometimes called YIGBY, or Yes in God’s Backyard—to encourage and enable churches and other religious institutions to build housing on their property. Last week, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill allowing faith institutions and some colleges to build affordable housing even if local zoning prohibits it.

Asked what they’d like to see in place of the vacant properties—and what a thriving Golden Gate would look like 15 years from now—neighbors who spoke with The Oaklandside shared creative and varied visions.

Villa, who started her jewelry business in her living room, wants opportunities for other designers to move into small studio spaces and shops.

“For the neighborhood to become more attractive, it will need to be more of a retail core, to get people walking—sort of like how it used to be,” she said.

In decades past, Freeman was part of multiple efforts to draw up plans for the area. He and students and Merritt and UC Berkeley proposed a bike path down Stanford, a farmer’s market, and featuring the seasonal Temescal Creek. But the experiences were demoralizing, he said, because city officials shut down the proposals.

Freeman would like the SYDA property to be “open to the public, rather than just these blank spaces.”

Seth Melchert’s dream for the SYDA properties would involve an Indian music school and school for the study of Indian scripture and philosophy. He’s in favor of senior housing and “a wellspring of nature growing.” A temple would round out the vision.

“I dream of spaces dedicated for young people to gather, and engage in study groups and diverse creative arts expression, possibly also creating and tending gardens for food and native plant cultivation,” said Carolynn Melchert. She’d like to see more street trees too, as the sweetgum trees planted by the city in the past have largely rotted and fallen.

For Marshall Street’s Bernardin, the concept is simple: small businesses, and housing.

“The two things we don’t have now,” he said.