A year after Oakland shut down its pandemic-era network of Slow Streets, the city’s transportation department is working on bringing the bike and pedestrian-friendly roadways back as part of the city’s redesigned bike plan.

At next week’s Bicyclist and Pedestrian Advisory Commission meeting, OakDOT will announce that some sections of its planned 70-mile neighborhood bike routes will be repurposed as Slow Streets. This will allow the city to add even more car-slowing infrastructure like speed humps and stop signs. The program’s main goal will be to encourage residents to walk, bike, and use other transportation options like scooters, and to discourage cars.

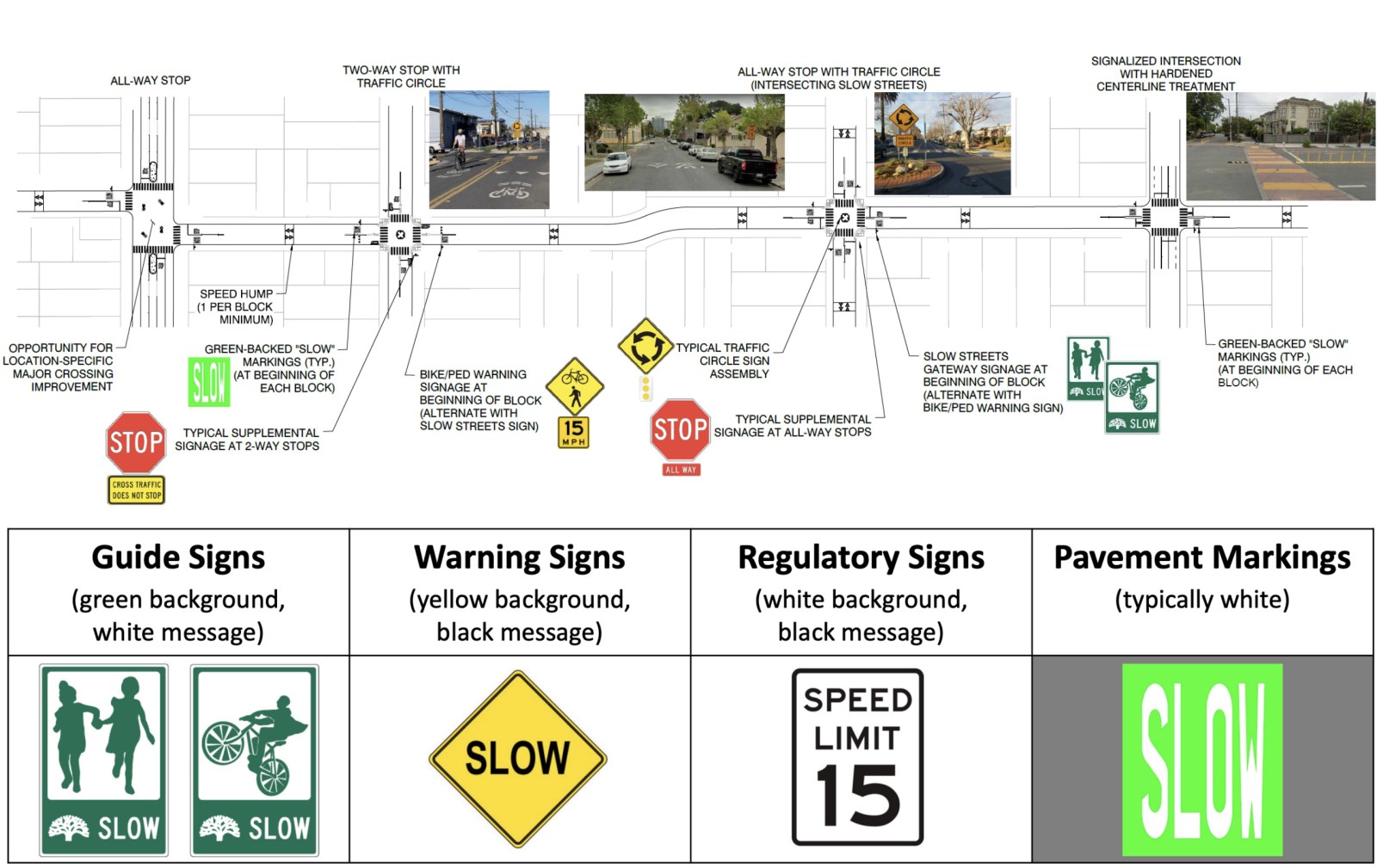

The new Slow Streets program will not be the same as what residents saw during the pandemic. The biggest difference is that through traffic—cars driven by people who don’t live or work on a particular street—will be allowed under the new program. The new Slow Streets will be designed to encourage people to drive at 15 mph, even though the city doesn’t have the authority to enforce this speed limit because of state regulations. This design will include signs and physical infrastructure.

The new Slow Streets will also take longer to go up. Where the first Slow Streets went up within a couple of months of the emergency declared by the city due to the pandemic, streets in the new program might not be complete until the end of this year or later, after city staff reaches out to communities where the routes are planned.

“No milestone decisions are being made at this time. We are proceeding slowly to work through the positive and negative lessons learned from the pandemic response,” said an email from OakDOT’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Program staff sent to residents.

Not all of the roads currently designated as neighborhood bike routes will become Slow Streets. According to OakDOT, this includes roads with medium-to-heavy vehicle traffic, those used by industrial trucking, and other roads that already function as critical corridors for emergency responders. “We won’t be successful if we pick streets that a lot people need to use as through streets,” Jason Patton, a Senior Transportation Planner for OakDOT, told The Oaklandside.

Part of Webster Street, which runs from Uptown to Temescal, is currently designated as a neighborhood bike route but will need additional design changes to become a Slow Street because of its critical through-way role for drivers. The city currently classifies Webster as a “collector street,” or a road that connects neighborhood streets to wider “arterial” streets with more traffic. 41st Street, on the other hand, is a neighborhood bike route connecting Broadway to Webster and OakDOT is looking to expand it as a Slow Street to the edge of Highway 24.

City staff plan to apply to the state for designation changes that will allow Oakland to turn Webster and similar collector streets, like Shafter Avenue in North Oakland and the southern part of 38th Avenue in Fruitvale, into Slow Streets.

Most of the roads that will be chosen for Slow Streets, though, will travel through single-family home neighborhoods.

Actual physical changes to the roads that can slow vehicle traffic will be added through the city’s five-year paving plan, approved by the City Council last year. The city will pay for these changes with Measure U infrastructure funds. The already approved Capital Improvement Program may also fund some road work. There are about 50 miles of streets that overlap between the paving plan and the current neighborhood bike routes plan.

Patton said the most important aspect from a systemic point of view is that the redesigned roads will seek to change people’s driving behavior.

“If your destination isn’t on the Slow Street, we are going to encourage you through design not to drive on that street,” Patton said.

A pandemic-era program that made bicyclists and walkers happy, but irked some neighbors

The city first rolled out its Slow Street program three weeks after the pandemic shutdowns in March 2020. The program’s initial goal was to close more than 70 miles of streets to provide “safe spaces” for people to enjoy by walking, riding bikes, or other non-vehicle uses. Most indoor entertainment and exercise options were closed at the time due to worries over airborne virus transmissions. The closures forced vehicles off these roads, except for emergency vehicles, delivery service cars, and cars driven by neighborhood residents.

The implementation of Slow Streets, which only ended up on 21 miles of roads, received mixed reviews from residents.

Supporters who lived in areas with better infrastructure, like Temescal and Rockridge, could take their kids onto a Slow Street to teach them how to bike, or they could enjoy a walk to nearby restaurants without worrying as much about speeding cars. Many of these residents worked from home during the pandemic.

East Oakland residents, on the other hand, were more critical of Slow Streets. They usually drive to work at locations outside their neighborhoods, and infrastructure in and around their communities tends to be in worse shape—fewer stop signs, no speed bumps, potholes, and more.

Public interest in Slow Streets continues

George Spies, an Oakland resident and member of the Traffic Violence Rapid Response advocacy group, says he is looking forward to Slow Streets reinvention. He lives on Webster Street and enjoyed how little car traffic there was toward the end of 2021. But by the time his neighborhood’s Slow Streets signs were taken down last year, Spies said that most drivers were already ignoring the rules and driving around the placards.

“They weren’t changing driving behavior. With them gone, we now have people driving past at 30 mph and running stop signs,” he said.

Spies, who attended the bike and pedestrian commission’s recent infrastructure meeting, said the city would like to use more traffic diverters in the flatlands. Diverters can be cement blocks, big planters, or metal rods that are placed above the roadway to create dead ends, one-way streets, and other barriers that reduce traffic.

“A principal idea they have is that a neighborhood is for going into and out of and not through,” Spies said.

Berkeley and other Bay Area cities have been using more diverters to slow traffic and make it harder for cars to drive through neighborhoods. Spies thinks adding diverters in largely low-income neighborhoods might actually bring more equitable safety that wealthier neighborhoods already enjoy. “If you look at the map of the city, as soon as you start going up the hill, there are diverters there. In the Lakeshore area, Crocker Highlands, Trestle Glen, and Oakmore. Those places are safer because of it.”

But OakDOT is proceeding cautiously with this idea because it might make it really hard for residents of East Oakland to get around.

Robert Prinz, the advocacy director of Bike East Bay and a member of the bike and pedestrian commission’s infrastructure subcommittee, said he is looking forward to riding his bike on the Slow Streets. He said a Slow Streets network could be even more fun for bicyclists than riding on protected or buffered bike lanes on arterial roads because multiple people can ride together.

“I actually really enjoy shared neighborhood streets because you can ride side-by-side,” he said. “They end up becoming very social sorts of facilities where you can ride as a family or friends and have a conversation.”

Tegan Hoffman, a north Oakland resident, told us she is “thrilled” the city is considering bringing back a version of the streets they used for two years.

“For the first time our neighborhood truly felt like a neighborhood where residents could enjoy their community by the places they live, especially since Oakland is a park-poor city,” she said.

Feedback wanted

When the first Slow Streets were set up nearly three years ago, many Oaklanders noted the flimsiness of the plastic and steel barricades the city placed at intersections made them easy to remove. A few ended up face-down in nearby ditches or were stolen. Many residents also complained that the signs were hard to read. “The temporary materials were not sustainable,” Patton told The Oaklandside.

This time around the city plans on installing permanent signs on metal poles, some which may feature kids riding scraper bikes. The city may also paint “SLOW” in giant bright letters on the pavement.

Sign visibility for these redesigned streets is quickly becoming a hot topic in other parts of the Bay Area. In San Francisco, a group of residents supportive of the city’s Slow Streets network, which includes 17 roads, recently sent their transportation department a letter demanding the city continue using colorful signs to mark the streets and avoid vehicular conflicts.

OakDOT told The Oaklandside it intends to reach out to residents on all local streets that might be affected, including busier roads. If the city chooses 38th Avenue as part of its Slow Streets network, a big arterial street like Foothill Boulevard and a collector street like Brookdale will obviously be impacted.

Prinz said the new Slow Street framework would help OakDOT staff analyze neighborhoods in their entirety to help them prevent the negative traffic impact residents saw in the program’s first iteration.

“Different neighborhoods have different street grids, connectivity destinations, and traffic types. The intention is to get a sense of how traffic is flowing, how people want to use the street, and then try to develop a solution that fits that,” he said.

OakDOT is taking email feedback about this project at oakdotbikeped@oaklandca.gov. Patton said the department is “trying to be realistic” about its capacity to respond to comments and incorporate them into the work.

“Pandemic Slow Streets generated a lot of interest, both positive and negative. We were overwhelmed by the volume of feedback we were receiving. In order to be more responsive, we are going to move more slowly,” he said.

Members of the public who wish to comment on Oakland’s new Slow Streets plan can attend the Bicyclist and Pedestrian Advisory Commission meeting over Zoom, which will take place at 6 p.m. next Thursday.