East Bay residents had their first opportunity Thursday to see new designs for the San Pablo Corridor Project, which is expected to reshape one of the region’s most important roads and its surrounding streets.

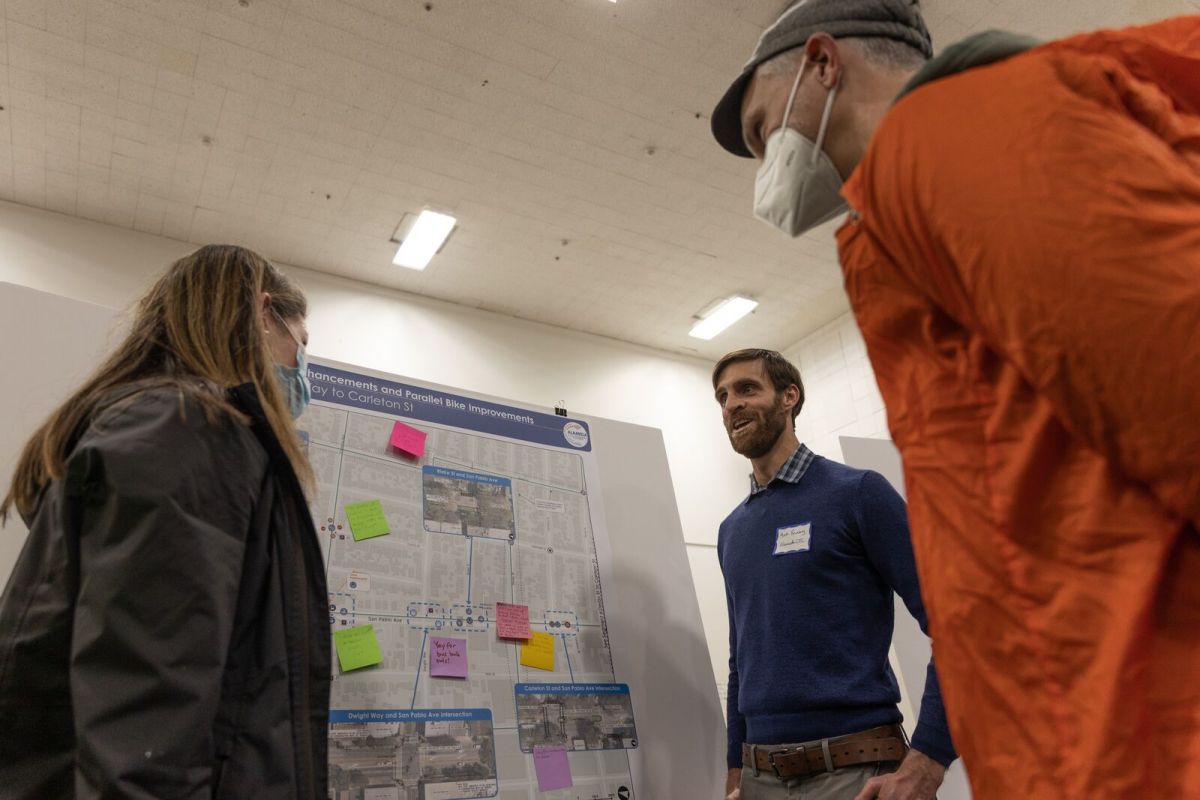

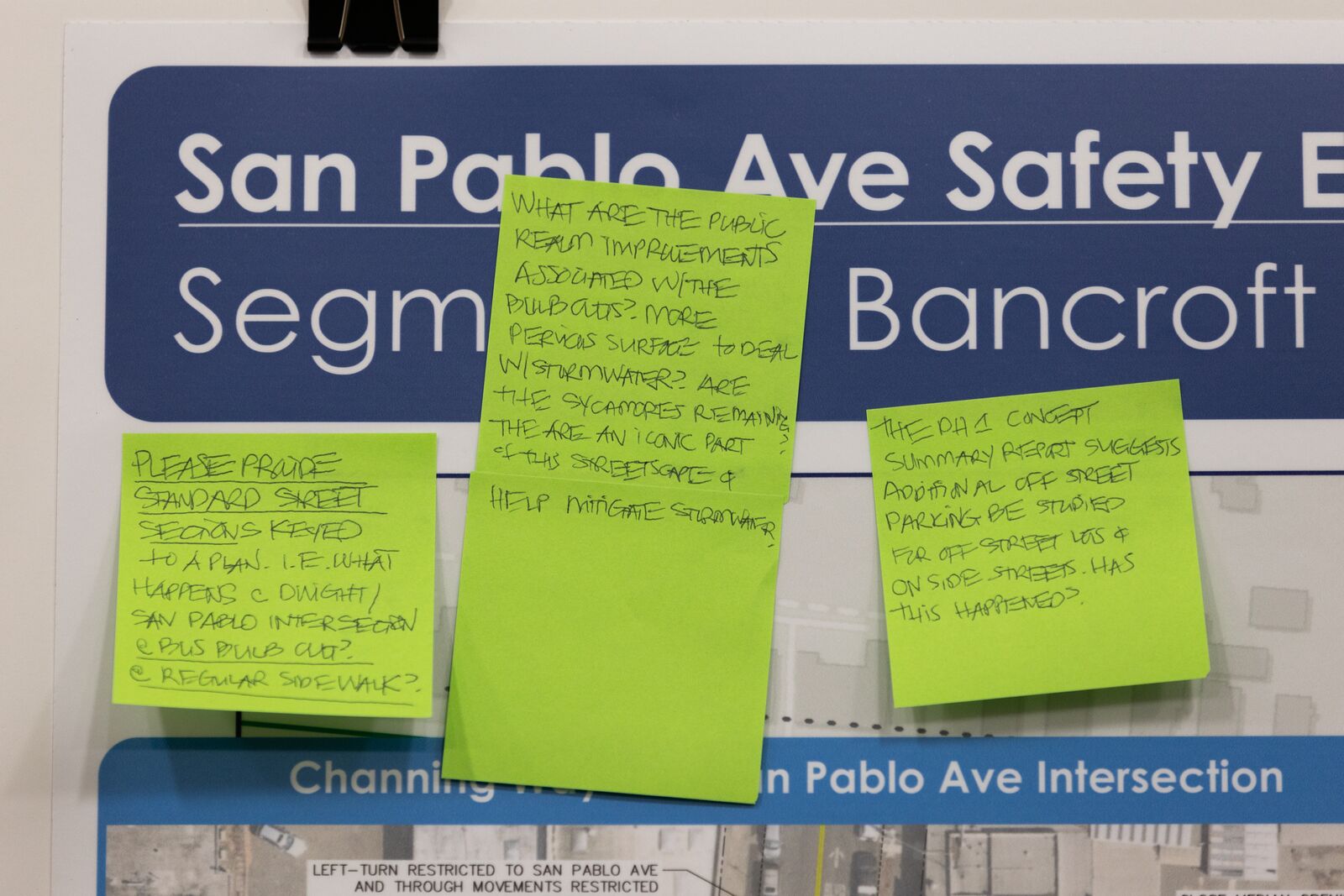

At a community meeting held at the Berkeley Adult School, the Alameda County Transportation Commission revealed designs for intersections on San Pablo Avenue and for the network of bike boulevards in Berkeley and Oakland that will run on sidestreets parallel to San Pablo Avenue. Over 100 people participated, sticking colorful post-it notes with feedback on poster boards displaying road redesigns.

Changes include bus stop upgrades, new traffic circles, pedestrian crossing beacons, and the removal of parking spaces to accommodate this infrastructure. The main goal of the redesign is to make the area safer for pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers. The project also seeks to “make transit faster and more reliable,” according to handouts made available at the meeting.

San Pablo Avenue has the most collisions of any street in the East Bay, according to state and county data. About 64% of collisions causing serious injuries and fatalities involve pedestrians and bicyclists, many struck by motorists, even though bike riders and pedestrians only account for 10% of the road’s users.

The redesign is particularly urgent for the county and the cities involved because they expect to see massive growth in population on and around San Pablo Avenue over the next decade, mainly through new residential and business development.

Last year, the county transportation commission approved spending $3.5 million in Measure BB funds for the planning, engineering, and design of San Pablo Avenue.

Last night’s event was the first of several community meetings this year where engineers can engage directly with East Bay residents. An Oakland-only meeting is expected this Fall.

Feedback ranged from praise to heated arguments to constructive criticism

Ryan Dole of the Kimley-Horn consulting firm, which works with ACTC on the project, said feedback from residents is important because it allows them to fast-track their learning around specific neighborhoods.

“You have to live in the neighborhood in order to have an intimate knowledge of the corridor,” he said. (For example, one local suggested engineers take into account the many delivery trucks that roll up to the ACME bakery when designing that particular section of San Pablo Avenue.)

The conversations were full of technical lingo and largely cordial. Ladan Sobhani of Berkeley said other drivers have collided with her car before on the street and she appreciated the personal interaction with people from the commission and the ability to talk about her fears.

“I really appreciate the safety enhancements, although I’m concerned about reducing lanes of traffic toward Oakland,” she said.

Several people did get into heated arguments with the engineers.

Cleo Masliah said she is worried the new bike lane infrastructure, including on Kains Street in Berkeley, will divert car traffic onto smaller streets, endangering residents.

“What these lane designs are doing [is they are] creating winners and losers. Winners are those streets who get bike lanes,” she said. “These are often the largest streets that could accommodate them, but parallel streets are now losers because now those cars are racing down. They were never meant to accommodate that type of traffic.”

Masliah said the creation of Slow Streets and the addition of temporary diverters during the pandemic already created some of those speeding conditions in her neighborhood, forcing residents to install their own speed bumps. Berkeley eventually forced them to be removed.

Mary Behm-Steinberg, a disability advocate, said she thinks the proposed changes are “dangerous” because she feels they don’t take into account the concerns of the disability community. She said the initial resident survey was “visually inaccessible, with spidery fonts” that could not be zoomed into.

“Our voices aren’t being heard,” she said “I’m worried about emergency vehicles not being able to get through.They are disadvantaging people who are already disadvantaged. Anything that limits vehicle road access is madness,” she said.

Robert Prinz, the advocacy director for Bike East Bay, said he appreciates the design process in the Oakland and Richmond sections of the project so far because they made it safer for all residents with protected bike lanes and dedicated bus lanes on San Pablo Avenue. But Berkeley, he said, is failing its safety goals by placing cyclists on a parallel “mobility boulevard” a block or more away from San Pablo Avenue. Because many will eventually travel to San Pablo Avenue, where most businesses are, he thinks they’ll be put at risk.

“On the way here, I saw a bike rider on the sidewalk, a mobility scooter rider in the street, and a food delivery driver parked at a bus stop in order to make a dropoff. I don’t see this project as addressing any of those things. There are people who are still going to need to bike or scoot or wheelchair in San Pablo,” he said.

Dole, the project consultant from Kimley Horn, said most of the project design decisions that are being criticized, particularly in Berkeley, are focused on “safety enhancements” in narrower streets nestled within residential areas. City residents had already rejected adding protected bike lanes on San Pablo Avenue because they didn’t want to lose more parking spaces there. So the changes to the side streets are necessary.

“The challenge was in seeing these competing interests and trying to find a balance,” he said.

Part of that balance, Dole noted, will require removing dozens of parking spaces in residential neighborhoods instead of in front of San Pablo Avenue businesses. Each placard displayed at the center yesterday included symbols with a negative number, delineating the expected number of lost spaces, most of which will be on the cornered end of residential blocks. This parking removal practice is known as daylighting, and it helps cars, cyclists, and pedestrians see vehicles better as they approach intersections. Many people on San Pablo Avenue, particularly business owners, are worried fewer parking spaces will lead to fewer customers.

George Spies, one of the leaders of the Rapid Response Traffic Violence group in Oakland, which has protested roadway deaths over the last year, said he wishes there was less focus on lost parking in the design presentations and more on the changes that will lead to fewer collisions, injuries, and deaths. He suggested that when the project is presented again, the consultants find a way to show how many people have been hit at specific intersections in recent years, to inform people’s input.

Spies said the focus on parking is an example of the commission and of Berkeley residents’ unrealistic understanding of what is going to happen on San Pablo Avenue over the next 20 years. The city’s rejection of protected bicycle lanes and bus-only lanes on the main artery will lead to more traffic in Berkeley as taller buildings are constructed along the corridor. Most of the people who live in these new buildings, he said, will not own cars and will be transit-dependent, bicycle users, or pedestrians who will expect better road safety to cross the street and intersections.

“We have to think forward and accommodate those changes that Oakland and Richmond and other cities are doing, and do it successfully,” he said.