Update, Jan. 21: The St. Vincent de Paul homeless shelter will reopen to guests Monday evening, according to the city.

City spokesperson Karen Boyd said that all shelter guests—the 25 who tested positive for COVID-19 and the several who did not—should have been offered rooms in the county isolation hotels.

“Unfortunately, as the City learned just today, some people who did not test positive but who were exposed during this outbreak, did not receive a referral. This was unfortunate, as close contacts are eligible for quarantine assistance,” Boyd said in an email Thursday. “City staff are now working with SVDP staff to locate those guests, and hotel rooms are available if they are located.”

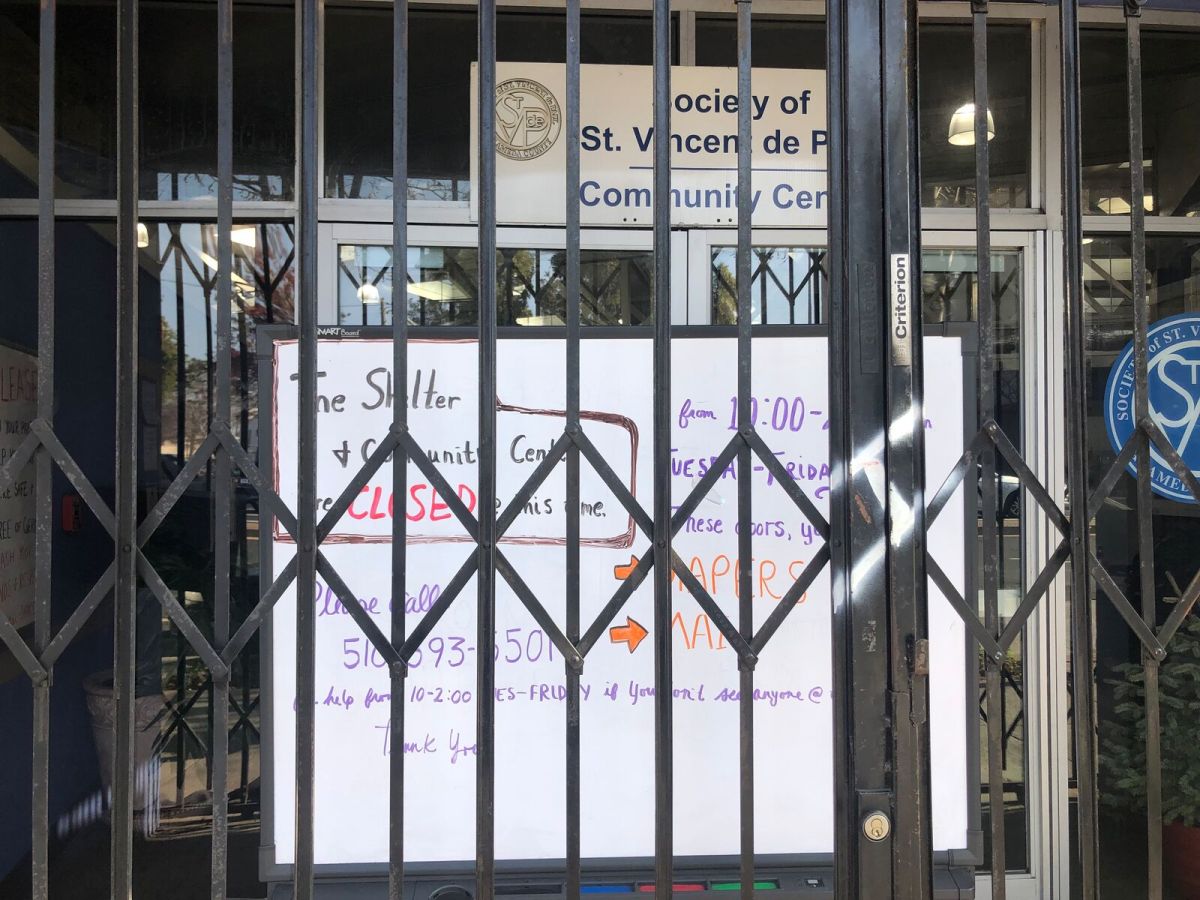

Original story, Jan. 19: A COVID-19 outbreak affecting some 20 unhoused residents and seven staffers has temporarily shut down a large West Oakland homeless shelter.

St. Vincent de Paul, which has operated its nightly shelter on San Pablo Avenue throughout the pandemic, closed over the weekend after numerous tests from earlier in the week came back positive. The city-funded shelter had been serving roughly 40 guests each night, and had recently received winter-relief funds to open an additional room on particularly cold or wet nights.

Seventeen of the guests who tested positive were moved into county-run isolation hotel shelters, where they can quarantine. A couple others declined to move there, said Blase Bova, executive director of St. Vincent de Paul of Alameda County.

“Almost all have been gotten into safer ground,” she said.

But that left at least 10 guests who did not test positive for COVID-19 to fend for themselves and abruptly find another place to sleep.

“It’s a horrible thing to be evicted from a shelter when you are healthy,” Bova said. “All we could really offer them at that moment was a blanket. I think the whole [shelter] system is kind of maxed out at the moment.”

It is not yet certain when the shelter will reopen. Bova said she’d like to wait until case rates in Alameda County are down to pre-omicron levels and employees are comfortable returning. But the city is encouraging a much earlier start date, possibly as soon as Thursday, she said.

No such thing as an “omicron-proof shelter”

When the pandemic began in 2020, many public health experts called for the closure of congregate shelter facilities—those like St. Vincent de Paul, where guests all sleep in the same room. They said the safest place for unsheltered people to live during the pandemic is in housing that allows them to stay by themselves or in small household groups. Some congregate shelters in Oakland, like the nearby St. Mary’s Center, stopped operations immediately after the virus began spreading.

“We now have very good data and studies that show that congregate shelter is not safe,” said Dr. Coco Auerswald, a public health professor at UC Berkeley and UCSF. She collaborated on a report in April 2020 that outlined the risks of indoor group facilities, where social distancing is challenging and isolating sick guests is impossible.

Unlike some other shelters, St. Vincent de Paul continued serving unhoused residents throughout the pandemic. Many people sleeping at the shelter have “reservations,” allowing them to stay long-term—some for several months at a time—and store their belongings there. The shelter also accepts some drop-in guests.

“We do have a congregate setting, but even in COVID outbreaks and surges, our model has been amazingly effective,” Bova said. Until last week, there had been just one positive case among the guests throughout the entire pandemic, she said.

Bova attributes that success to the large distances between beds, regular testing, required masking (staff wear N95s and guests are offered them), and a high vaccination rate among guests.

Omicron pierced the armor of our model.

Blase Bova

“We have a culture where people are really looking out for each other, trying to keep each other safe,” she said. Her experience at St. Vincent de Paul led Bova to believe that congregate shelters were still much safer than encampments, where residents, although outdoors, are exposed to numerous other health risks, as well as a lack of distancing and masking.

But “omicron pierced the armor of our model,” she said. The highly contagious variant has caused case rates to skyrocket among both housed and unhoused residents, according to the county.

“There is no way to have an omicron-proof shelter,” said Auerswald, noting that even people living in shared apartments or houses are very likely to get exposed to the virus currently.

Seven of the St. Vincent de Paul shelter’s 12 staff members also tested positive, Bova said. All staff have been guaranteed two weeks’ pay, and those who have continued working received temporary raises, she said. Other St. Vincent de Paul programs, like its curbside meal service, which provides 600 meals a week, have continued operating.

The organization had already been short-staffed for months before the outbreak, however, and city workers have been stepping in on an emergency basis.

Hundreds isolating at county hotel shelters

County isolation shelters—mostly repurposed hotels—have seen an inundation of hundreds of residents, including the 17 from St. Vincent de Paul, needing to quarantine over the past week.

In late December, there were 25 unhoused people isolating in quarantine hotels, said Jerri Randrup, spokesperson for the Alameda County Health Care Services Agency.

This past weekend there were more than 400.

“We added approximately 230 rooms…and have worked around the clock to keep up with referrals,” she said in an email. “The omicron surge brought a dramatic rise and we reached capacity on Saturday yet were able to accommodate referrals.”

Alameda was the first county to participate in Project Roomkey, the state program funding hotel shelters. Thousands of people have now stayed in the hotels, some of which are reserved for people who test positive and others designed for longer-term, preventative stays. Hundreds of those residents were set up with permanent housing after the hotels.

Auerswald said that, throughout the Bay Area, officials could have gone further in taking advantage of state and federal funding—and empty hotels—to keep many more residents safe.

“Two unsafe options should not be the only options,” she said, referring to congregate shelters and outdoor encampments. “It’s really critical for us to decrease the risk, and the only way to do that is to provide proper housing.”