Five candidates with a wide range of professional backgrounds are competing to represent District 7 on the Oakland Unified School District’s school board. District 7 includes Oakland’s easternmost neighborhoods from wealthier areas in the hills to working-class flatland communities near the airport and Coliseum. There are 27 schools in District 7, the most of any of the city’s seven districts. The winner will take over from James Harris, who is stepping down after 8 years in the seat.

Candidates identified outdated and inadequate facilities, pollution and other environmental concerns, the growth of charter schools, and a more expansive curriculum, as important issues they hope to address.

Listening to residents—while not always agreeing with the majority

In interviews with The Oaklandside, several D7 candidates stressed the importance of community engagement.

Kristina Molina, who works as a communications coordinator for the Alameda County Assessor, said she has divided her supporters into caucuses representing different groups, including parents, youth, and Black residents. By meeting with each different group during her campaign, Molina said she can hear from all kinds of students and families in District 7.

Molina is concerned with the stress and trauma that many students in deep East Oakland experience due to gun violence poverty, and how this affects their education. If elected, Molina said she would establish what she calls a “first responders team” that could include teachers, counselors, or other school staff who would work closely with students who have failing grades to find out what’s preventing their success in school, and create means to help them achieve.

“I believe that brown and Black children are incredibly smart and incredibly talented. But they are being faced with a tremendous amount of stress by living in the flatlands, and that needs to be counteracted by more resources in our public schools,” Molina said.

Clifford Thompson, an elementary school teacher in Richmond, said his biggest priority is making sure that community voices in the district are heard. One area where he breaks with a majority of the OUSD community is on the topic of school police. In June, the school board voted unanimously to disband its school police force and create a new safety plan that doesn’t include campus police officers. Thompson thinks a complete elimination of school police went too far.

“Totally dissolving the police, I don’t feel is the appropriate thing to do right now,” he said. “I think there are some people that would take advantage of other people, if they knew that there was no recourse that the person could take.”

Thompson thinks a reduction, not a complete elimination, would have been a better option. He would rather see some funds spent on retraining police.

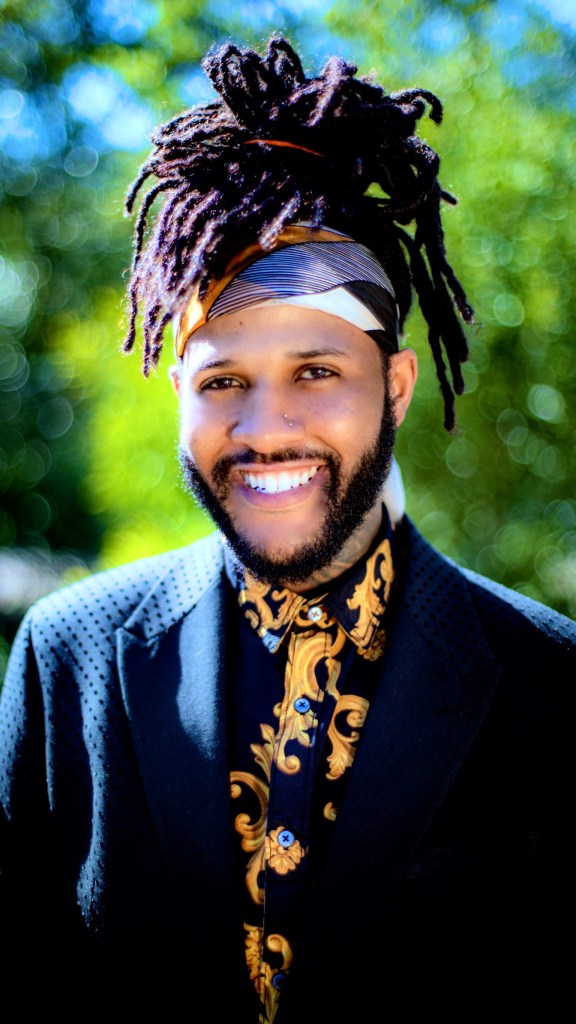

Bronché Taylor, a program coordinator with the Oakland Public Education Fund, says meeting regularly with District 7 residents is how he’ll get feedback and update constituents about what’s being discussed at school board meetings.

“I really, really believe that a lot of people are not aware of the different policies and how public education works, and it doesn’t serve them,” he said. “And there are people who are benefiting off of communities not being informed.”

Ben Tapscott, a former basketball coach at McClymonds High School and a public school advocate, said community members encouraged him to come out of retirement and run for the school board. Tapscott has been active with the New McClymonds Committee, an alumni group that has opposed school closures and raised questions about what the district is doing to clean up environmental contamination at McClymonds High School in West Oakland.

“A lot of people have faith in me because my track record shows that I’m going to do similar things [for District 7],” Tapscott said. “We need to listen to our parents and listen to some of the things that they see are problems.”

Victor Valerio, a project engineer for the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, wants to strengthen the board’s relationship with the public. Growing up in East Oakland, Victor said he felt his voice was heard as a student at Fremont High School, but when the state took over the district in 2003, community input was lost. The district came back under local control in 2009, but Valerio feels a relationship with the community needs to be forged again.

“I feel like the school board hasn’t listened or heard the concerns,” said Valerio. “And there’s been a lack of responsiveness from the district, particularly in East Oakland.”

Repairing old school buildings will be costly

Candidates had mixed thoughts about Measure Y, a $735 million bond that’s also the ballot this election. If passed by voters, OUSD could borrow hundreds of millions of dollars to update facilities across Oakland campuses, including modernizing D7’s Elmhurst United Middle School.

Valerio serves on a civilian committee that oversees school bond measures passed in 2006 and 2012. Bond mismanagement, as detailed in a recent Alameda County Grand Jury report, was one of the factors that prompted him to run for the school board this year. The grand jury found that OUSD spent millions in bond funding on projects that don’t explicitly support students, like paying rent at the district’s downtown offices, and left other projects at school sites unfinished or over budget. Valerio supports more transparency and a stricter oversight role for the board regarding bond funds.

Tapscott, who has been outspoken about the need to improve facilities at McClymonds, says he originally opposed Measure Y because of the district’s history of bond mismanagement. He has asked OUSD board members at previous meetings what measures they plan to put in place to monitor how bond funds will be spent. Once he saw that several people running for the board this year have platforms centered around financial accountability, Tapscott changed his mind about the measure, which he now supports.

Still opposed to the bond measure is Taylor, who previously taught arts and theater at McClymonds High School and at D7’s Castlemont High School. Taylor doesn’t think parents and the community were adequately involved in deciding which projects Measure Y will fund. And the $735 million will only place a Band-Aid on a larger problem, Taylor said. The total amount needed to bring OUSD’s facilities up to date is more than three times the amount Measure Y will authorize the district to borrow.

“If we need $3 billion, then let’s tell the community that we need $3 billion. $735 million is not going to fix a $3 billion problem,” Taylor said.

A facilities master plan that the board adopted earlier this year spells out the upgrades needed throughout the district; they total more than $3 billion. Because of limits in how much a school district can borrow, the bond will raise only $735 million. During a meeting in June, school board members had to choose which projects to fund and which could wait. The project list approved in June included funding for an administrative building, so that OUSD can end its lease at 1000 Broadway in downtown Oakland.

“Too often, taxpayers are asked, especially by the district, to trust and believe in what [district officials] are doing,” said Taylor. “But there is a lack of transparency and a lack of engagement.”

Candidates say there’s a greater need for budget transparency

Many of the people running for school board across the city this year have promised to be more transparent about the budget. OUSD has a yearly budget of about $600 million, but the board has made painful mid-year cuts in the tens of millions for the past several years.

Thompson, who was the principal of the Community School for Creative Education, a charter school in District 2, and a summer principal at Oakland Technical High School, thinks OUSD has too many contracts with consultants and outside organizations. If elected, Thompson said he will examine the need for those contracts and explore ways for the district to create new revenue, like increasing attendance.

OUSD, like other districts in California, receives funding based on average daily attendance at its schools. Just over half of the students in District 7 attended school consistently through March 13, before schools closed because of the coronavirus pandemic. That’s lower than the 60% of students district-wide who attended school consistently through March.

Thompson supports Proposition 15, a statewide ballot measure that would overhaul Proposition 13 by taxing commercial property based on its current value instead of on the property’s value at the time it was purchased. If passed, Prop 15 would raise billions more in new revenue that could fund cities, counties, school districts, and community colleges in California.

Molina, a mom of four OUSD boys, wants to see higher real estate transfer taxes on high-value residential properties to provide more funding to the district. A similar idea was proposed by City Councilmember Dan Kalb three years ago to raise revenue for the city and was approved with 69% of the vote. And she wants to see more details about the budget made available to the public.

“You have to really put out a budget that is transparent and that is easily read by everyone so that parents can understand where every nickel and dime of their children’s education is going towards,” she said.

In the name of transparency, Tapscott said, he would like to see a quarterly audit of the district’s finances to prevent surprise cuts during the budget process. Right now, an independent audit is conducted of the district’s finances annually. Similarly, Taylor called for an outside investigation into the district’s spending habits, similar to the grand jury’s 2019 report on how OUSD manages its bond funds.

School closures

District leaders, including administrators and some board members, have said for years that OUSD has too many schools for the number of students it serves, and that by closing schools the district can stabilize its budget and serve students more effectively.

we asked each candidate to fill out a detailed questionnaire. read their answers here.

Ben Tapscott did not return a questionnaire.

But many candidates have argued that the district’s closure plan, the Blueprint for Quality Schools, disproportionately impacts communities in East Oakland. In 2019, District 7’s Alliance Academy was closed and merged with Elmhurst Community Prep. Roots Academy, in nearby District 6, was closed. Frick Academy and Oakland School of Language in District 6 were merged. Futures Elementary and Community United Elementary, also in District 6, will merge next year.

Tapscott, who has been a longtime critic of school closures in West Oakland, doesn’t want to see any more campuses shuttered. Molina believes school closures contribute to low attendance rates, since closing neighborhood campuses could mean that parents have to travel further to take their children to school.

“Parents don’t have the economic funds to drive their children to school. At the end of the day, they’re making a decision: Do I spend $20 on the gas and take my son to school? Or do I spend it on food?” Molina said. “I think more schools should be open that could be in the proximity of children at a walking distance, especially in the flatlands.”

Charter schools

Of District 7’s 27 schools, 11 are charters—and nearly half of the students in D7 schools are enrolled there. Valerio thinks having a single school system is the most efficient way to educate children, as opposed to having district-run schools and dozens of charter schools that are independently managed. He supports a moratorium on new charter schools, but doesn’t want to divide parents who chose charters and parents who send their children to OUSD-operated schools.

“I also don’t want to vilify them. I don’t want to alienate them. Because that’s a conversation to have: How can we improve within our school sites, to where we can reduce the number of charter schools and strengthen public schools?”

Tapscott takes a hard stance against charter schools, arguing that they contribute to OUSD losing money.

“The students transfer to a charter school. The money follows the child, and then we have a drain on the budget,” he said.

Schools receive funding based on attendance, and if students leave OUSD for charter schools, the district loses funding that then goes to the charter school. Molina does not want to see any new charter schools and views charter organizations as privatizing public schools. Charter schools are public schools run by independent nonprofit organizations and appointed boards that are not elected by voters.

The Oaklandside is here to help you vote

Nuts and bolts: How, when, where to register and vote, and what you’ll be voting for

District coverage: D1 | D3 | D5 | D7

Oakland ballot measures: Y (school bond), RR (higher dumping and blight fines), QQ (youth school board vote), S1 (stronger Police Commission)

All about: Voting in person | Voting by mail | Using ballot drop boxes

The Oaklandside doesn’t make endorsements, but we’ve compiled local voter guides for you.

“I’m also going to advocate for parents and the charter schools to see where every nickel and dime of their children’s education is going to,” Molina said about her proposal to make charter schools’ budgets more public.

Taylor sees charter schools as a way for parents to exercise choice.

“They offer parents in marginalized communities options, when a lot of times they’re not given that. They’re not given the ability to make a decision,” he said. “It’s important for parents to feel like they have some control.”

Thompson, who has worked in district-run schools and charter schools, thinks both can exist as long as both types of schools are succeeding. If any school is failing, whether a district school or a charter school, he says, it should be closely scrutinized.

“I think we have reduced the discussion of charter schools versus district schools to an acrimonious debate where we’re talking about things instead of putting our focus on the kids excelling,” Thompson said.

Curriculum and academics

Like candidates in other races, D7 contenders have concentrated on OUSD’s literacy rates and test scores. For Tapscott, a better curriculum could also lead to better attendance at D7 schools.

“If you improve the curriculum, you will improve the enrollment,” Tapscott said. “We need to enrich the programs at the three schools: Fremont, McClymonds, and Castlemont. And if we do that, hopefully students will attend schools in their neighborhood.”

OUSD has open enrollment, which means students can attend schools in any neighborhood. In the hills of District 6, 31% of students who attended Skyline High School last year actually lived in the Castlemont High School area, according to district data. That’s higher than the percentage of Skyline students who live in the Skyline area, 29%. About a quarter of Skyline students live in the Fremont High School area, in District 5.

Tapscott said the mix of schools in District 7 needs to be improved. Of the 16 district-run schools in D7, 11 are elementary schools, one is a middle school, one is a 6-12 school, and Castlemont is the traditional high school. (D7 also includes two alternative schools.) With so few middle schools, Tapscott believes elementary school students leave the district after fifth grade, or attend a charter school, and don’t end up returning to Castlemont. Last year, Castlemont enrolled just 819 students of the 1600 it can support.

“If we look at the enriching programs, the elective programs that will keep kids in school, as well as sports, we have another way of improving enrollment and another way of kids learning,” said Tapscott.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that an administration building was not part of a Measure Y project list. Funding for administrative facilities is included, but as a district-wide initiative, not as a site-specific project. And the tiered real estate transfer tax Measure X was approved by voters in 2018.