This fall, voters in four Oakland City Council districts —1, 3, 5, and 7— will get to pick their next city councilmember. Two years from now, voters in districts 2, 4, and 6 will have their turn. Oakland is one of many American cities with district-based elections, meaning only people who live in deep East Oakland’s District 7, for example, can vote for District 7’s City Council and school board reps. Candidates running in D7 can focus on knocking on doors and earning votes only in that district, and not have to campaign across the whole city.

Fans of district-based elections say they give residents more local control and let more people run for office by making it less expensive. “District elections are more accessible because you shrink the geographic area and number of voters a candidate has to reach,” said Jonathan Stein, the executive director of Common Cause California, a voting rights and government transparency group. “A person who has people-power, but maybe not financial resources, can mount a viable campaign.”

District elections have also given Black Americans, and other communities that have suffered from housing and school segregation, more power to pick their own leaders.

But Oakland’s political system wasn’t always like this. Before 1980, Oakland had a system of “at-large” elections that forced anyone running for City Council to earn votes across the entire city. The outcome, according to Robert Stanley Oden, a political science professor and author at California State University Sacramento, was that Black and Latino residents were virtually shut out of local politics.

“African Americans lived in West, North, and East Oakland, but they could never put together enough votes to bring somebody onto the council because the white community really dominated the process,” said Oden. This was especially evident in District 3, which encompasses West Oakland. By the 1960s, Black people made up the single largest racial group in District 3, but their council representatives were uniformly white, and later Asian, and less progressive on housing, jobs, and policing.

This changed in 1980 when voters passed Measure H, which tied Oakland City Council elections to individual districts. Measure H was the culmination of decades of political conflict. On one side were Black activists who wanted seats on the City Council and white progressive allies who felt neighborhood issues were being ignored. On the other side was Oakland’s old power structure, centered on big businesses and white Republican politicians who had controlled City Hall for decades and opposed district elections, warning they would return the city to a bygone era of Tammany Hall-style ward bosses and corruption.

“It was a critical change in Oakland politics,” Wilson Riles, Jr., said in a recent interview about Measure H.

Riles was elected to the City Council in 1979 representing District 5, which encompasses the Dimond District. He was the third Black Oaklander ever elected to the City Council. Riles and a handful of other Black politicians campaigned alongside activists for Measure H and helped a whole generation of Black leaders break into politics.

But while Measure H ushered in greater racial and political diversity on the council, in the long run, the shift to district elections wasn’t the political revolution some hoped—and others feared.

Demise of Oakland’s ‘corrupt’ ward system

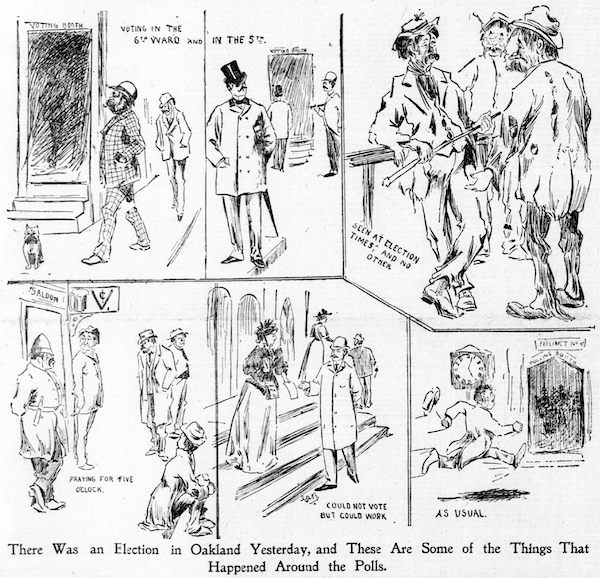

Oakland actually started out with district-based elections. In the late 1800s, it was called the “ward system,” and as in other American cities, Oakland’s ward bosses—the influential men who ran neighborhood saloons, businesses, and labor unions, and who could swing hundreds or thousands of votes in an election—were known to engage in corrupt practices.

According to historian and Fordham University professor Chris Rhomberg’s book about Oakland’s political history, No There There, the city’s wards were controlled by newer white immigrants, many of them Irish, Italian, and Portuguese Catholics who worked in burgeoning industries on the waterfront. Although these “machine” politicians provided jobs and services to their constituents, “City Hall was plagued by charges of favoritism and corruption,” wrote Rhomberg, and “public administration was widely regarded as incompetent and untrustworthy.”

This situation infuriated Alameda County’s growing white, native-born Protestant community, including major business leaders in the region who portrayed themselves as crusaders for transparent and clean government. Organized through the Republican Party, this coalition attacked the ward system and won several major changes starting in 1889, when four citywide or “at-large” council seats were added to Oakland’s City Council to dilute the power of representatives from the city’s seven wards. The city’s growing population of middle-class white residents, who largely lived in expanding neighborhoods in the hills and east of Lake Merritt, were able to pick these four councilmembers year after year by sheer majority.

In 1910, the ward system finally ended when voters amended the city charter so that all councilmembers, who still had to reside in the districts they represented, were now elected through a citywide vote. This substantially undermined the power of immigrants, Catholics, and other minorities, but, Rhomberg notes, it still wasn’t enough to assure that Republican conservatives could completely control the city.

In 1931, voters further consolidated the power of Oakland’s white Republicans by taking away the mayor’s power to direct city staff. Now, only a city manager could run the city, and the council and mayor were largely limited to creating new laws.

Although most of these reforms were framed as being about “good government,” Rhomberg writes, they had the effect of concentrating power in the hands of white conservatives and disempowering immigrants. At the time, the Klu Klux Klan was very active in Oakland, and its leaders—mostly white native-born Protestants, including city officials and leaders of the business community—made it clear that the city’s new form of government was designed to disempower “alien” groups.

According to Rhomberg, Oakland’s Black and Chinese communities represented a combined 6% of the city’s population at the turn of the 20th century. Neither held any political power, and both were barely scratching out a place in the economy. For “most Black workers, occupational segregation was a fact of life, reinforced by other groups’ prior monopolization of the ethnic labor market,” Rhomberg explained. “At the bottom were the Chinese, denied naturalization and the right to vote.”

Though the KKK had by the 1940s largely disappeared as a powerful anti-immigrant, white supremacist force in Oakland politics, according to Rhomberg, the city’s white middle class “transferred their allegiance from the faulty vehicle of the Klan to the more effective anti-machine reformers among the business elite.”

As Black migration to Oakland grows, the Tribune supports politics as usual

By 1957, those reformers ran the city by controlling most City Council seats through at-large elections, and by having their representative in City Hall in the office of the city manager. This was the first year, however, that Oakland’s at-large system was challenged.

Oakland had grown immensely since the days of the ward boss, and one of the city’s biggest changes was the arrival of tens of thousands of Black migrants from the South. Black people settled mainly in West Oakland and sought to participate in local government as their community grew, but the at-large system guaranteed Black candidates could never be elected. The citywide white majority rejected any Black person who ran for office.

Many others were also tired of the at-large voting system, including some middle-class neighborhoods populated by white residents. They felt hyper-local issues like potholes and parks weren’t getting enough attention. Upset also were local merchants who felt that city government wasn’t responsive to the concerns of small businesses, and that too much attention was focused on helping big businesses operating at the port. This coalition sponsored Proposition 11 in 1957, a proposal to bring back district-based voting.

But the Oakland Tribune newspaper, owned at the time by the Republican U.S. Senator William Knowland and his father, Joseph Knowland, who were close allies of the region’s big businesses, campaigned vigorously against the measure. On March 31, 1957, a Tribune editorial linked the proposition to “communistic support,” part of a Cold War foreign plot to undermine America. The paper later quoted Harold Lorentzen, a local businessman and Chamber of Commerce director, calling Proposition 11 “the most vicious threat to clean government in Oakland.”

Just before the election, on April 14, 1957, the Tribune printed an article with no byline quoting West Oakland incumbent councilmember Howard Rilea, another opponent of district-based elections. Rilea used a different argument, warning that if Oakland got rid of at-large voting, “the people of West Oakland would be prohibited from voting for six members of the council—a two-thirds majority.” Rilea, who was white, represented the part of Oakland where the Black population was growing fastest, and likely would have been voted out of office if district residents had a say.

As Oakland’s only major newspaper at the time, the Tribune had a monopoly on daily news and rarely quoted supporters of Proposition 11. That spring, the proposal was defeated two-to-one. That year, three white men were elected by citywide majorities to council districts 2, 4, and 6.

The growing push for Black representation on the council

But Oakland was continuing to change. In the 1960s, Civil Rights Movement organizers mobilized against redlining, which kept Black people crowded in substandard housing in West and East Oakland’s flatlands. They protested discriminatory employers who kept them locked out of good jobs in factories and downtown department stores, and challenged mistreatment by the police. In the late 1960s, Black Power became the goal, and many activists looked to politics to make change. These activists identified the at-large election system as an impediment.

In 1967, Elijah Turner, chairman of the Oakland chapter of the national Congress on Racial Equality, mounted a campaign for the City Council’s at-large seat, which represented the entire city rather than any particular district. He called for the council to immediately use federal funds to build public housing, and for the city to address abuses by the police.

“Right now, there is complete unanimity on the City Council,” Turner was quoted as saying on the campaign trail. “I am running to win, not just as a protest candidate. When I am on the City Council I will be there to raise the questions that no one else will raise.”

In West Oakland’s District 3, three other Black residents ran for the council seat that year. The Oakland Tribune was blunt about their chances: “The other three in this race are Negroes seeking to represent this predominantly Negro district, difficult to do when the vote is city-wide.”

“The black people in this city can either be a political force or have to continue to be a disruptive force. This is not a threat, but it is a reality.”

Oakland CORE chapter Chair Elijah Turner in 1968

Turner lost, as did the three other Black men running in D3, but the next year he and other activists continued to register Black voters, who were slowly becoming a force in local politics.

Black Oakland organizers demanded the city establish a civilian police review board to rein in the brutality of OPD. No existing councilmembers, including Raymond Eng, a Chinese-American optometrist and Boy Scout leader elected in 1967 to represent West Oakland’s District 3, and Frank Ogawa, a Japanese-American nursery operator who represented East Oakland’s District 7, were in favor of this.

Realizing they needed their own representatives on the council, Black leaders pushed to reform the city charter and bring back district-based elections. Oakland’s mayor, retired Air Force colonel John Reading, dismissed the idea, recalling “ward boss” fears of the past. “It promotes graft and smacks of Tammany Hall,” he told the Tribune in 1966.

“It’s feared that power tends to corrupt; but the lack of power tends to disrupt,” Turner, the Black at-large candidate, told a Tribune reporter in 1968. “The black people in this city can either be a political force or have to continue to be a disruptive force. This is not a threat, but it is a reality.”

As before, others were also pushing back against the at-large voting system, which was also used to elect school board representatives. In 1970, a young Black Oakland attorney named John George filed a lawsuit against the city alleging that the system “operates to so minimize the voting strength of minorities as to disenfranchise them.”

Mayor Reading called the lawsuit “divisive” and said the city would fight it.

Shirley Chisholm’s presidential run electrifies local Black organizers, and a Black Panther runs for mayor

Activists continued to push against the limits of Oakland’s election system. In 1972, a Mills College student named Barbara Lee invited Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, to speak on campus. Chisholm told the students she was running to become president of the United States that year. Lee joined Chisholm’s campaign.

“I was president of the Black Student Union and working with the Black Panther Party as a community worker,” Lee said in a recent interview. “We were passing out food to people. I was on public assistance, too, during that period.” Lee said that many Black Oaklanders in the early 1970s were “disenfranchised” and lived in despair due to high rates of poverty.

Lee convinced Huey Newton and other leaders in the Black Panther Party to throw their support behind Chisholm. Over the next few months, they registered voters in Oakland and the Bay Area.

“People were so happy,” said Lee about how Black Oaklanders responded to the registration drive. “They were excited. It was the first time they’d ever talked to anyone about registering to vote.”

In 1973, Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale ran for mayor of Oakland alongside fellow Panther Elaine Brown, who campaigned for a seat on Oakland City Council. The duo mobilized low-income voters of all races like never before in the city. White liberals also supported Seale and Brown, and Seale forced Mayor Reading into a runoff election.

“My position is that now, in many different cities and countries, the masses of poor, oppressed people can be made the majority of registered voters, as we have done in Oakland,” Seale told an interviewer before the election. “We made the Black community there the majority of registered voters. We also have the Spanish-speaking community, the young, progressive whites working with us, too.”

Lee, now a member of Congress representing the East Bay, said the Panthers’ prior push into electoral politics with the Chisholm campaign ensured that “the machine was already there for Seale’s campaign. It was turnkey.”

“Seale took a majority of votes in the flatlands precincts,” said Riles, the Black former District 5 councilmember, who worked alongside Lee on the Chisholm campaign. “But the incumbent mayor had frightened the people in the foothills and hills so much, with this cry that Bobby would do away with the police and crime would rise, so they turned out 90 percent and higher in the hills.”

Seale and Brown lost the election, but their campaigns continued to build momentum toward something greater.

“The uprising around the Vietnam War and the Black Panthers was really beginning to have its effect on the ground, in terms of local politics,” said Riles, who still lives in Oakland. “A lot of communities began to feel some sense of power and ability to change things at the local level.”

In 1973, Leo Bazile was a law student at U.C. Berkeley and part of the Niagara Democratic Club, a local group of Black activist attorneys. He credits Seale and Brown’s campaigns with laying the groundwork for the final demise of Oakland’s at-large elections system. “Seale lost to Reading, but his campaign opened the door to someone with more legitimacy” in the eyes of more white Oaklanders, Bazile said in a recent interview.

That someone was superior court judge Lionel Wilson, who in 1977 became Oakland’s first Black mayor. Wilson wasn’t a radical, and many white moderates who voted against Seale picked Wilson over the staunchly conservative Reading. But according to Bazile, Riles, Lee, and others, the biggest reason Wilson won was because of the consciousness-raising work the Panthers had put in for over a decade, and the new Black voters in the East and West Oakland flatlands the Panthers had registered and energized.

The Panthers had also been instrumental in helping John George become the first Black person to win a seat on the Alameda County Board of Supervisors in 1976. Black political power was also evident in Ron Dellums’s successful 1970 campaign to represent the East Bay in the U.S. Congress.

“To many minorities and white liberals in Oakland today, the system has taken on an appearance of an un-democratic—even oligarchic—holdover from what the minority population remembers as the bad old days.”

San Francisco Examiner, 1980

But even with these breakthroughs, the barrier of citywide elections remained in Oakland.

In 1979, Elijah Turner ran for office again, this time for the District 3 council seat representing West Oakland. While he garnered a majority of votes within the district, his opponent, Raymond Eng, a Chinese-American optometrist with more conservative politics who had first taken office in 1967, garnered a majority of votes from hills precincts and won the race.

Two San Francisco Examiner reporters explained the situation in an article the following year: “Practically speaking, a candidate now running for office in the West Oakland ghetto, for example, can lose in that district and yet win the election by outdistancing his opponent in the well-off, predominantly white Oakland Hills.”

The reporters concluded, “To many minorities and white liberals in Oakland today, the system has taken on an appearance of an un-democratic—even oligarchic—holdover from what the minority population remembers as the bad old days.”

But Wilson Riles, Jr., who ran for the District 5 seat that year, prevailed over longtime councilmember and conservative Fred Maggiora. Once in office, Riles, along with Mayor Wilson and Alameda County’s first Black supervisor, attorney John George, combined forces with other officials and activists and campaigned for district-based elections.

“There was a recognition that this was an opportunity to consolidate this change,” said Riles. “The history had been that no matter what district a councilmember represented, their votes really came from the hills.”

In 1980, a proposal to return to district-based elections appeared on the ballot as Measure H. Oakland voters overwhelmingly approved it, with 44,000 voting yes and 28,000 no.

Bazile was elected to the council in 1983 to represent District 7, a part of the city that had long before become majority Black, but was for the first time gaining a Black representative.

While Black political activists were key to this change, Riles said two other forces played a role. One was the decline of big corporations that had tended to endorse and finance conservative white councilmembers. The other was white voters who joined in calls for change.

White progressives in the foothills and hills started to recognize that district-based voting could benefit them, too. John Sutter, a liberal white councilmember elected in 1968 who was known for advancing environmental policies, joined the push for district elections.

“When they built 580 freeway, the middle-class, mostly white neighborhoods, liberal Democrats, pushed back,” said Riles, recalling the controversial highway construction project in the 1960s. “John Sutter was a leader in that fight, and even though they didn’t stop the 580, they forced the state to build sound barriers and make it a less impactful freeway on the neighborhood. Sutter and his community gathered enough political power to win a council seat, and from then on, Sutter was a lone voice on the council, but he was able to raise a lot of issues.”

Diversity grows, but wealthy residents and outside interests still shape local elections

After 1980, the City Council’s complexion and politics permanently changed. By 1992, four of the city’s eight councilmembers were Black. Oakland was electing Latino councilmembers and continued to see Asian representation on the council, along with white politicians who continued to represent more affluent parts of the city like districts 1 and 4.

But the diversity of elected officials hasn’t sparked the transformative politics some hoped and others feared it would.

According to Oden, the political scientist at CSU Sacramento, money remains a moderating influence on city politics, even with district-based elections. “It takes a lot of money to run for City Council,” said Oden. “That limits the ability for progressive candidates to win,” because they can’t as reliably turn to businesses, landlords, and the astonishingly tiny proportion of residents who contribute to local political campaigns to raise money and pay for advertising.

“District elections alone are sometimes not enough to allow true community-rooted candidates to run for office,” said Stein of the voting advocacy group Common Cause California, who served on Oakland’s Public Ethics Commission for three years. “In Oakland, you see candidates who have to fundraise from out-of-city donors, or in districts where the wealthiest residents reside.”

A 2018 study produced for the Public Ethics Commission found that 93% of campaign funds for City Council races came from less than 1% of the city’s population, and that money for elections often originated from the same small group of people and companies over and over again. The PEC released a new report this month showing that half of the money in Oakland elections originates from contributors based outside the city, many of them corporations.

“You have to prove yourself to this small class of donors before you can mount a viable campaign,” said Stein. “This is particularly true in the lower-income districts in which communities don’t have the money they need to donate to candidates.”

According to the PEC report, successful campaigns for the district 2, 4, and 6 City Council seats in 2014 averaged $93,000 in expenditures. In 2016, this went up to $112,000 for the district 1, 3, 5, 7, and At-Large seats.

Riles, who retired from the District 5 City Council seat in 1990 to unsuccessfully run for mayor, agreed that the cost of running for City Council has had a negative impact on the city’s politics. Without a big grassroots organizing push like the one the Black Panthers briefly sustained, money has proven especially powerful in Oakland’s poorer districts. “Particularly in districts where people are most impacted by poverty, you see folks getting elected based on being able to raise big amounts of money for mailers and other campaign ads,” said Riles.

But Stein said that Oakland’s move to district elections was still a huge step forward for democracy.

“In the Jim Crow south, at-large elections were an explicit tool of disenfranchisement,” said Stein. “There were even some cities that had district elections, and when the Black community grew large enough that it could elect its own councilmember, the city explicitly moved to at-large.”

Bazile, the Black councilmember elected in 1983 after Measure H , said that as much as district elections changed what’s possible in Oakland, and despite the real barriers posed by the high cost of running, he thinks another big obstacle stands in the way of a real community-powered politics: apathy.

“District elections were fine,” said Bazile. “They’re still fine. The problem is getting people to vote in local elections.”